Featured Worlds have found themselves to be a bit neglected so far this year, with not a single game being added to the list yet. The trouble is always in feeling like I'm the sole decision maker of what gets relegated to the "very good game" category. With new worlds, I hate to jump the gun and call something a classic because I quite enjoyed playing it last week, and so I try to let new releases sit and see how fondly I remember them later. Other streams and Closer Looks provide good opportunities to discover overlooked titles that deserved better when they were new, though looking at the list of past articles for the year, I haven't really ran across anything too spectacular. What has shown up on my radar this year has been plenty of older games that I'd describe as good:

- Nivek's Outlaw - An adventure about a town guard being threatened with violence to permit smugglers to bring weapons into the city. When the smugglers are later caught, his name comes up and he is accused of siding with them. What follows is a surprising twist of a coup and the disgraced guard supporting the people that cost him his home and family.

- James Holub's The Lost Pyramid - An adventure with two different routes through the game that I played for myself in a Closer Look back in 2022, fell in love with, then streamed this year only to have a much less glamorous experience with it on my second time through.

- clysm's Crunchy - A sci-fi action title, and the renowned author's first release. It was a bit confusing in terms of its story, whose successors are far more notable. Highly recommended for those who have played his other games, less so as a high-quality pick.

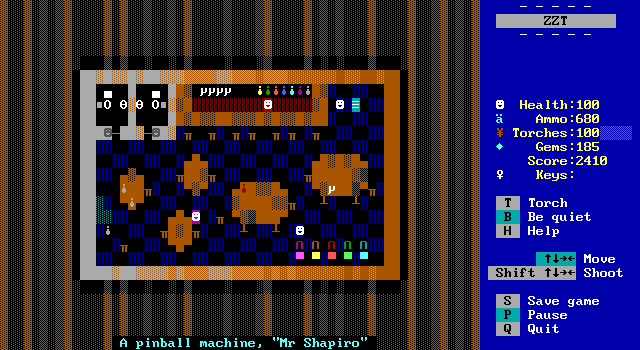

- Eurakarte's Year of Shapiro - A collection of Shapiro games that range from good to excellent, that I played too recently to want to revisit just yet, which also suffers from some of its most interesting games being incomplete.

- Orange698's The Score - I just got done with this. I also described playing it as torture. My opinion on this one fluctuates more rapidly than its marketplace's prices. Possibly good, possibly not.

None of them really feel right to give a permanent spotlight to, though I'd definitely recommend checking them out at least partially if they sound interesting to you. A fair share of newer titles could fit if I was willing to break the seal on them so early, and a few other older titles that were pretty great already have the older Game of the Month status. Maybe one day I'll be prepared to provide more substantial reviews rather than the 500 words-or-so of their vintage reviews, but for now the search would have to continue.

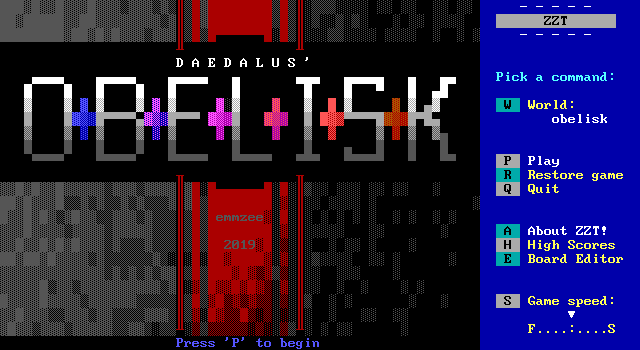

Little do you all know, that I have a small list of safe picks for when the time is right. (AKA I realize it's been like nine months since the last one.) Making a choice requires replaying the game to get some screenshots, and to confirm that it still holds up. To no surprise of anyone who was around in 2019, that list contains Daedalus' Obelisk. A game released smack in the middle of the modern ZZT renaissance created by longtime (and I do mean longtime) ZZTer Darren Hewer, who made his return to the scene with an adventure that has a rather unique perspective.

Daeadalus' Obelisk is an easy game to recommend for just about anyone. There's appeal to a number of potential audiences here. Simply the return of Hewer was enough to get others rediscovering the ZZT scene at the time immediately interested in a new release.

Hewer can lay claim to having the longest legacy of a ZZTer. Thanks to the donation of personal floppy disks from from his youth which were archived and added to the Museum, he now shares the honor of the earliest known non-official ZZT release with 1991's Coolzap. It's the earliest example of a game that shows that right from the start ZZT was giving children the incredible ability to create their own video games. Obelisk meant a twenty-eight year history of working with the engine, and a return to ZZT after a twenty-one year hiatus. Anyone hoping to claim the title from Hewer now would need a game today and their first release to be from 1993 or earlier.

Over the years Hewer has built up a history of acclaimed titles and awards. He was the first place winner of the Winter 2000 24 Hours of ZZT contest with Parroty, the 3rd place winner in the Summer 1998 24 Hours of ZZT contest (the very first one!) with Dreamling, and created the Classic Game of the Month plus Featured Game award winning Death. All this, not to mention an earlier history of colorful adventures throughout the early 90s, mean Hewer's name is one spoken with great respect. In terms of both quality and quantity, odds are that anyone who had the ability to download ZZT worlds has played at least one of Hewer's games, and almost certainly remembers them fondly.

So when Hewer returned one day, and asked me if I'd be interested in helping to beta test his new game, a ZZT platformer that revolved around the player rather than using the far more typical style of engine seen in other platformers, I leapt at the chance to see what he had cooked up.

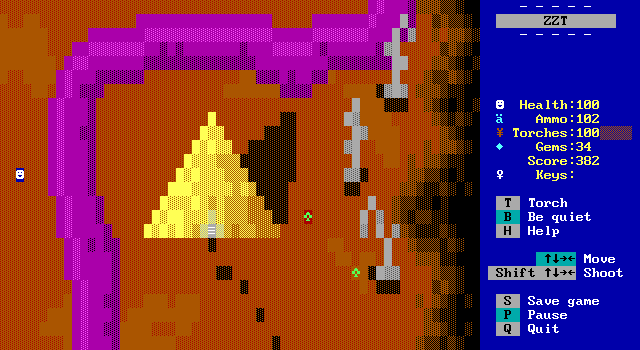

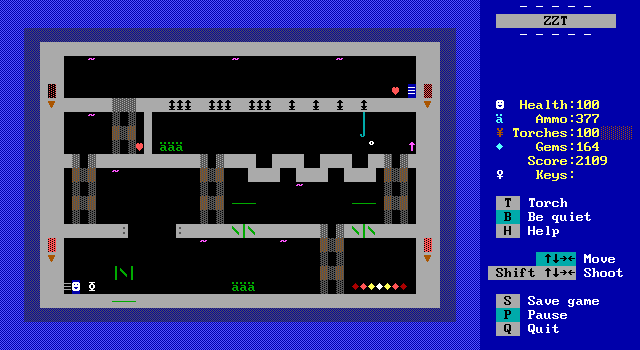

Daedalus' Obelisk, turns ZZT on its side, creating a directly player controlled platformer that ditches the clunky grid-based physics seen before it. It instead provides new kinds of challenges and obstacles with an emphasis on restricted movement, shooting foes, and avoiding hazards. The game does so in ways that really hadn't been done before, relying on a clever idea of pinning the player between the ground and a row of invisible water. By doing this, Hewer was able to transform the overhead(-ish) ZZT engine into one viewed from the side. With players unable to move freely, old gameplay mechanics could seen from a new angle. Even if you thought you've seen everything in ZZT, Hewer was ready to introduce something new to the almost thirty year old engine.

The use of water specifically for the barrier between ground and air allows both players to shoot upward and for enemies to shoot down from above. All the while, using the actual player element rather than an object means that other objects can much better track and detect the player. Hazards will only strike the player via #IF CONTACT. Enemies can move and shoot relative to the player rather than doing so without any idea of where they're going/aiming. Items can simply be touched, rather than awkwardly running checks to see if an object-player failed to move and then assuming that that being blocked in the opposite direction means it's the player character trying to grab the item. Yes, this means no phantom grabs where players suddenly grab items from across the map because a bullet was adjacent to them. Play is significantly smoother than say, Freak Da Cat 2.

Whether you're comfortable even calling the design an "engine" depends on how strict your definition is. The player's abilities aren't compromised in any ways with code. Moving and shooting all abide by the out of the box rules of ZZT, yet the rest of world has its own requirements. Water restricts movement while allowing bullets to move freely. Players can "levitate" their way up stairs to higher levels, suspending themselves in the air on a single permitted tile, though this is no sillier than any number of console platform heroes supporting the rest of their body mass in the air as long as a single pixel of foot is above a platform. For more organic methods of movement, ladders, ropes, elevators, and vines are the prevalent ways to move the player vertically.

A notable omission, and perhaps my one frustration with the game, is the lack of gravity for a free-falling mechanic. The level design often seems perfect for players to clear off a platform, then walk off the edge to plummet safely to a lower level rather than turning back and descending a ladder to reach the same area. The player's refusal to step anywhere other than solid ground sometimes led to me trying to reach a particular location in a way that was actually impossible, wasting time and requiring stopping to study the screen in order to find the correct route. I can't actually fault Hewer for this, as the reasoning behind it is almost certainly a technical one.

The best I could come up with would be to have an object above the immediate empty space #PUT S BOULDER repeatedly, instantly dropping the player down. Shooting would then have to go through the object, so it would have to see which direction it was blocked in just before being shot, and then fire in the opposite direction? That much might work, though I'm not sure how you'd then keep players from climbing up against gravity from the bottom without yet more objects, and they'd have to move out of the way at certain times, and they can't directly block the player from below since then they couldn't shoot north...

Needless to say, the omission isn't merely "forgivable", it's to be expected. The trouble is that walking off a ledge is such a natural thing to do in a platformer, even the heavily compromised ones in ZZT, that the urge will lead to moments where you'll find yourself unthinkingly trying to. Sonic and Mario have no issue here, as are all the lemmings that weren't assigned blockers. Gravity is surprisingly absent from Daedalus' Obelisk. Falling is simply irrelevant for player and enemy alike.

With everything about the engine hinging on the use of invisible water to keep players locked in place vertically, you might expect the game to be a tad noisy. Between failed attempts at walking off edges and frantic movements up stairs to escape enemies, there are plenty of opportunities to break the illusion of what "up" means in Obelisk. The shrill plink of ZZT's water sound effect and helpful reminder along the bottom of the screen that ZZT wasn't designed with the game's non-conventional gameplay styles in mind are certainly unwanted. Though longtime ZZTers are likely used to the mismatch of water (as well as breakable and fake walls) as it was designed versus how it gets used in practice, nobody is really a fan of it.

The 2010s onward in ZZT have placed much more emphasis on polishing things up for a better player experience along with extra care being taken that your game may end up being someone's introduction to ZZT. To that end, Hewer included a copy of Nanobot's 2002 CleanZZT, a hex edit of the program that blanks out the messages and audio for water, fake walls, and forests. This allows players to hold up to their heart's content and relish in the sound of silence, making the game feel less hacked together in the grand ZZT tradition of finding creative uses for its various components. To a non-ZZTer playing the game, CleanZZT might fool them into thinking that what Hewer is doing here is simply another mode of play offered by ZZT.

Admittedly things can still be quite noisy even with CleanZZT keeping the player from being a source of noise.

Okay, two frustrations.

Again, it's not Hewer's fault. Some of the more object-enemy heavy dungeons can get a bit loud thanks to the sound effect played whenever a bullet is fired. Combine this with duplicators constantly making their own horrible cacophony and some boards can get almost uncomfortably noisy for how long players will spend on them. Muting the game with B is always an option for those that aren't equally annoyed by ZZT being completely silenced. Something like CleanZZT back in the day could have located other noise sources and silenced them (and given how common the Koopo method of changing boards was, I'm surprised it didn't), but I don't think Hewer's hiatus would have ended if part of the deal was for him to pore over ZZT with a hex editor to do some audio work.

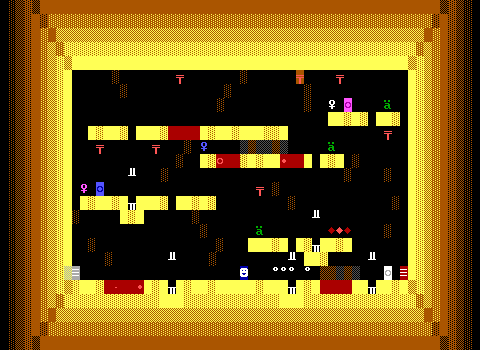

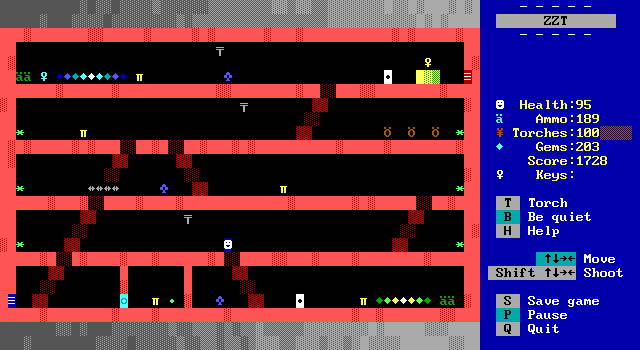

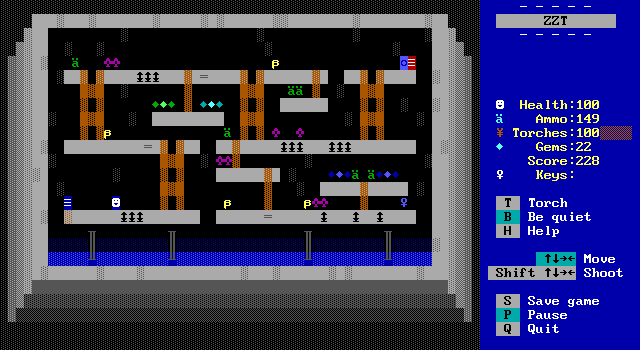

The noise is loud, yes, but it's also a sign that things are happening. Obelisk contains eight dungeons for players to conquer, each consisting of two boards (with one exception) before players can take on the Obelisk itself which is a gauntlet in comparison. The dungeons are colorful, varied, and distinct from one another. One could imagine a simplified version of the game focused entirely on screen after screen of levels to complete, but Hewer went for the more complex approach of creating an entire world map to house the dungeons as well as adding characters and a story to give everything more of a purpose than merely "Reach the exit". This makes for a far more interesting journey than a basic arcade-style game.

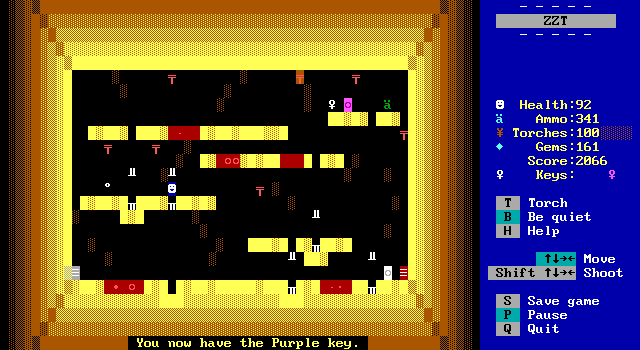

The dungeons still sit at the heart of the game's premise. Any platformer needs interesting stages, which Hewer has no issues delivering. Daedalus' Obelisk lets players tackle the dungeons in nearly any order (two require items from other dungeons to be acquired in order to venture through them) so there's no real order to follow, or deviate from here. The non-linear aspect is less to encourage replays and more to keep players from having to hunt down a correct location with the dungeon they'd be intended to go to next. The game limits players to 100 health and provides a few sources of healing which reset you to maximum. Unlike other non-linear games where a surplus of health, or lack of ammo after finishing one region can greatly impact how the next plays, Hewer opts to reset players so they're always able to take on a dungeon from a good position.

Ammo is still limited, with opportunities to purchase it or win it here and there. It's hardly something to worry about, as the levels themselves contain more than enough ammunition. Outside of your first dungeon, where you'll still have enough ammo, but not so much to fire with reckless abandon, it would be quite difficult to not end up with a surplus. Shopping is a safety measure in case something really does go wrong, rather than a key component to the player's success.

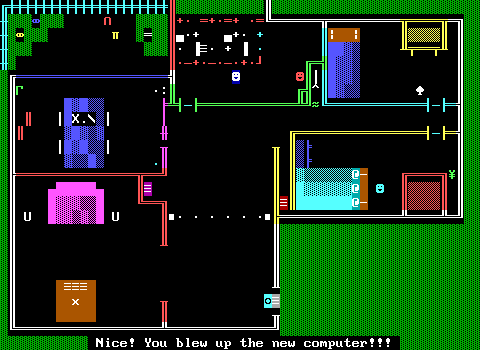

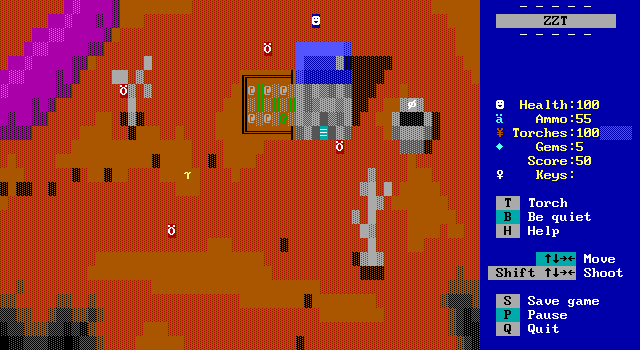

While there's no such thing as "level one", Hewer does subtly guide players to one of the dungeons which makes it a likely first level. This dungeon is located in the castle which players are strongly recommended to visit right away. Here, players get an explanation of the game's story and motivation for entering each level along with justification for laying claim to the magical keys found within. After getting all the info, players can investigate the secret of the castle they heard about and discover a hidden passage behind a bookshelf. This one makes a solid first impression, though even if it's missed initially, none of the freely accessible levels seem too difficult to start with.

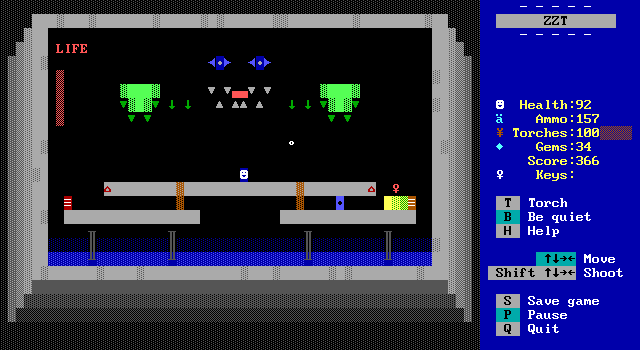

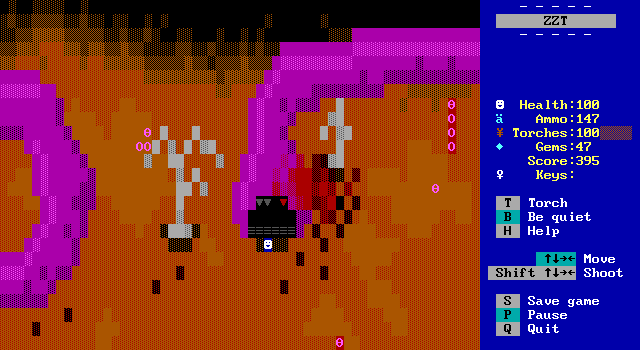

In the castle level, players get a nice introduction to the game's primary form of platforming action. It's a mix of default ZZT enemies with some strange yellow "things". A number of pressure plates are scattered across the stage, positioned so that players are forced to land on them, causing the things to throw a star and vanish. Since stars can cross water, these projectiles can effectively fly here, asking players to learn quickly how to maneuver around them and making sure they have their escape route planned before stepping on the next plate.

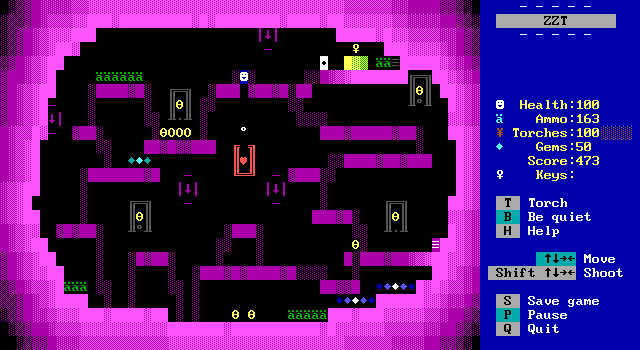

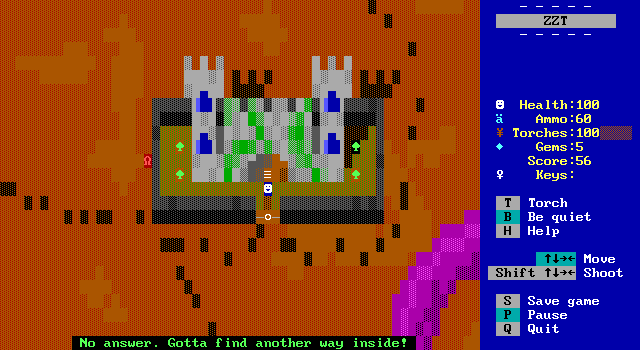

Its second board is one of the most impressive in the game. While a few dungeons have some form of boss battle, they're generally smaller in scale. Here, a massive figure appears to protect Daedalus' key from being pilfered. Large bosses like this in ZZT tend to have a bark much worse than their bite where being locked into a single position makes it very easy for players to move in, shoot a weak point, and dart right out to safety. These fights make for good looking screenshots and nothing more, offering only the minimal challenge unless accompanied by distractions that end up being more threatening than the boss itself.

In this instance however, the player's limited possibilities for movement radically enhance the fight. The monster's claws each need to be shot at, which will then cause its fangs to part momentarily, giving a clear shot at the foe's tongue. Once struck, the monster takes damage and everything resets. All the while players need to weave between sentry gun fire as they move from one clawed hand to the other, with the monster summoning bears on the far ends of the platform the entire time.

It creates a steady rhythm with plenty of room for mistakes if you get impatient or spend so much time focusing on shooting the claws that you don't realize a bear is at your back. The fangs will themselves eventually move back into position and reset everything if players aren't fast enough to line up their shot. It's fast paced and a lot of fun, guaranteed to convince players that they're in for something really special with Daedalus' Obelisk.

The gameplay is equally matched with visual flair. Claws shrinking to indicate they've been struck on a given cycle is obvious enough, and essential to give players feedback that they're on the right track with their attacks. Other details aren't to be taken for granted. The way the monster's eyes begin to blink as players awaken the beast, a rippling red wave of pain shooting outward when the tongue is shot, a previously invisible health bar for the fight appearing at its onset. Heck, even the spawn points for the bears begin to blink rapidly to indicate an incoming bear. So much is communicated to the player that you just wouldn't see in earlier ZZT games. It does an excellent job of making the game feel like it's much more than another ZZT rigid platformer of the 90s.

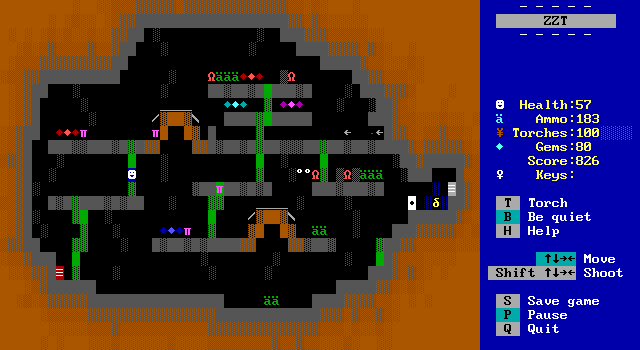

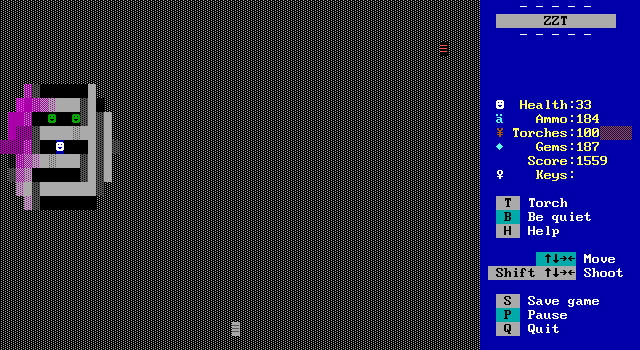

In one instance, the dungeon itself is the boss! Entering the maw of a massive purple tentacle leads players to the creature's heart which is mostly protected by a rotating wall. To reach the gap in the defenses, a complex layout of purple platforms with squiggly shapes to climb between them must be navigated. During this time, spinning guns are strategically placed to routinely get in your way, and a series of duplicators constantly supply fresh centipedes to slow players down.

While not as animated as the castle's guardian, it's hard to ignore the frantic pace set by the duplicators. You'll be running laps around the circular arena, shooting this way and that as you make your way towards a platform where you can finally shoot your shot and slay the beast.

Every dungeon offers something new for players to interact with. Any fears that the gameplay style can be compelling enough to hold one's interest for an entire game are quickly put to rest.

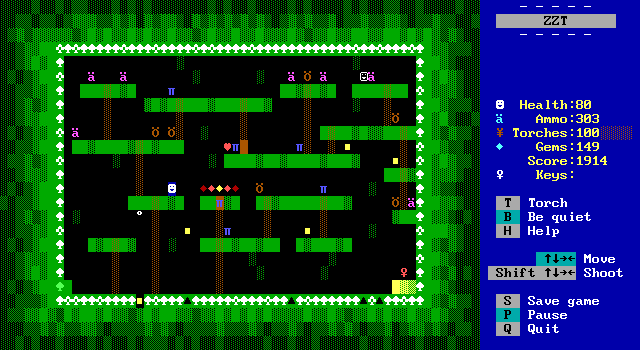

The prison is filled with zombies, objects that lurch towards the player and get back up soon after the first time they're knocked down.

Ghosts in the crypt fly erratically, shooting ectoplasmic bullets at the player. They can be stunned, but never defeated.

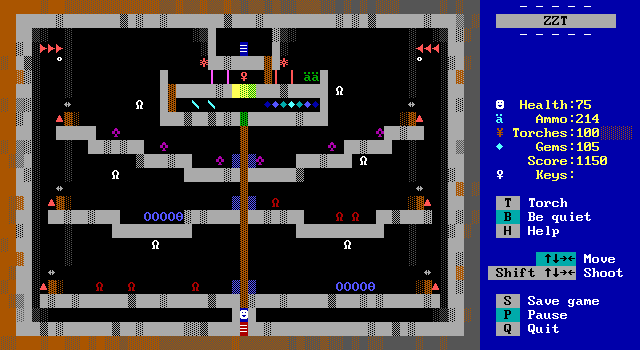

The pyramid hosts pits of lava, one-way transporters, elevators, and Mario-esque pipes consisting of line walls with transporters on either side.

You'll find switches that open doors, move sliders, block star-throwing enemies. You'll push boulders to flatten spikes. You'll grab keys while dodging automatic guns that will fire at an intruders. Almost everything in the ZZT toolbox is put to use in a way that provides challenge and excitement. Spinning guns, blink walls, lions, tigers, ruffians, sliders, transporters, keys, doors, bombs...

What Hewer has come up with is an original style of gameplay capable of making everything old new again. The levels are playgrounds enticing players to run and climb all around with never a dull a moment as they do so.

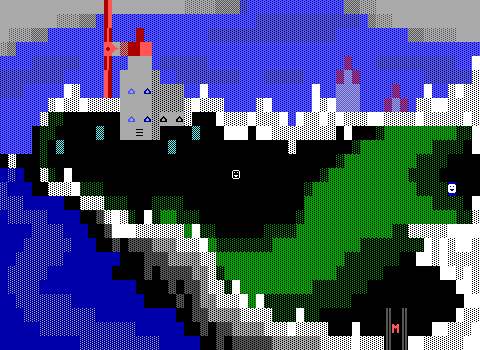

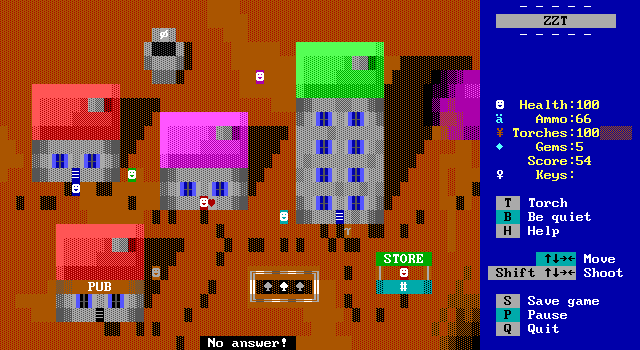

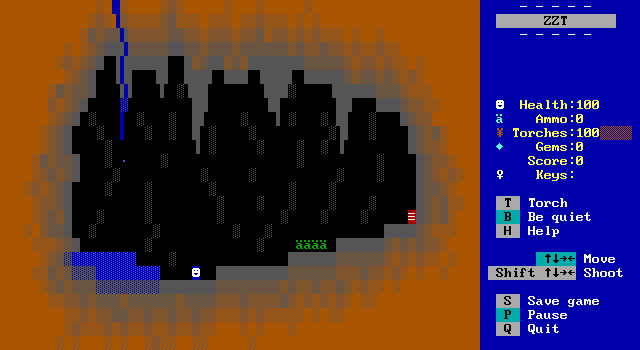

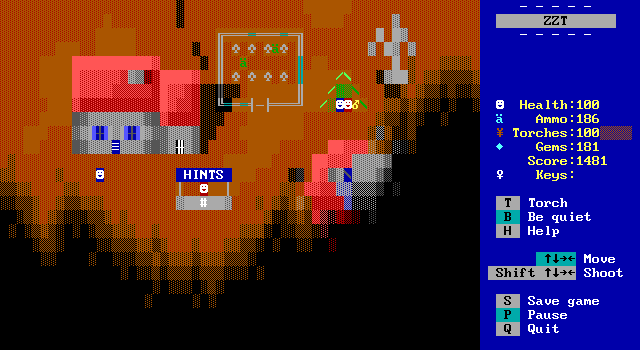

For a breather, look no further than the game's world map. Dungeons need to be discovered by the player themselves by exploring the desert wasteland that is the surface. A reasonably sized world map of twenty-three boards (5x5 with a missing corner) is large enough to provide a sense of exploration and discovery while being small enough that you're never far from where you're looking to go.

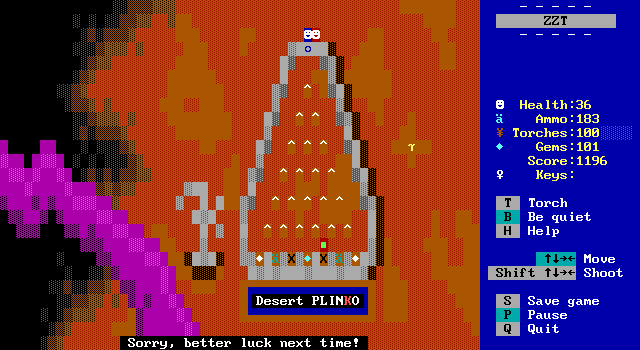

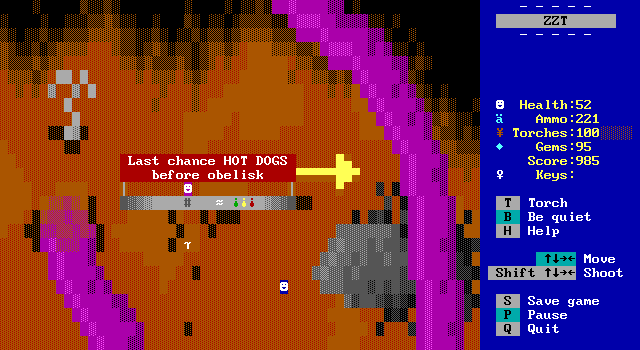

The game comes with a world map for easy reference. (Hewer suggests exploring on your own for a little while.) All but three of the boards have a label for some landmark of interest. Aside from the dungeons, there's a town, a hot dog stand, a toll-bridge, a zoo, and even a Plinko mini game where you can win ammo and gems if you're lucky. Not to mention a few secret bonus rooms that lean into the association of platformers and Super Mario Bros.

The valley turned wasteland players find themselves wandering is no longer the peaceful place it once was. Roaming packs of monsters prowl the map, incorporating a little bit of ZZT's usual four-directional action. It's far from the focus, compared to other games with world maps like Fred! 2. However it still has a place, preventing players from feeling safe holding down a direction until they reach a new location. These encounters are easy to run from and easy to handle most of the time, though beware letting monsters congregate along the edge of a board if you don't plan to take them down. A careless traveler racing from point A to point B without a care may end up walking directly into the lion's den when entering a board from a different direction than they left it!

Of course, there are actual roadblocks in the way as well. Environmental storytelling is the buzzword of choice on the surface. Withered trees that have been turned to stone interfere with movement, and it's certainly hard to ignore the massive purple tentacles which block travel and force the player to find alternate routes to places they can see, but not explore. Tracks worn into the dirt help naturally guide players to places of sanctuary. The remains of a young challenger to Daedalus can be found close to the obelisk's entrance. It's undoubtedly a harsh wasteland, but for once it's not barren.

Exploring the world map is also necessary to discover where you are and what you're doing here. Cleverly, Hewer didn't start the game in the middle of town or similar sanctuary. Instead it begins with players inside a small cave, getting them immediately used to the side-view used in dungeons. The player awakens in the cave with no idea how they got there, but avoids the cliché of not knowing who they are.

You are Eric, an everyday person from our world. The last thing you remember is going to the pub for some drinks and then waking up here. Over indulgence is Eric's best guess as to what to lead him here. The truth, as players discover, is far stranger then a bender.

Emerging from the cave, Eric finds himself fenced in on a small ranch with a gate that requires a code to open. This literal gating prevents players from wandering off before they know more of the story, forcing them to enter the home and speak with Virgil, who is also confused about the specifics, but has a much better idea of what's going on.

Virgil cuts to the chase: the land of Dagda was once peaceful and a heck of a lot greener too. One day a wizard named Daedalus appeared, demanded to be put in charge due to his magical abilities (nobody even believed magic to be real), and when he was rejected, he cursed the land. Daedalus has cut Dagda off from the rest of the world, enveloping it in darkness, killed the vegetation, tearing up the landscape with those purple tentacles, and then erected the obelisk he now watches over from, waiting for the people of Dagda to stop resisting and accept him as their new superior.

In order to enter the Obelisk, six magical keys are required, which are locked away in the various dungeons that have since sprung up whole cloth as well as by corrupting other locations since the "cataclysm" as the people now refer to the event. Many brave souls have tried to get these keys, but all have failed. Now it's Eric's turn.

Eric is then given the code to the gate along with directions to both the castle where the council will surely want to speak with him and to the town where he can get some supplies.

At that point, nothing stops players from roaming the entire world, though signage and an interest in getting the full story make visiting the castle first a sensible priority. Still, if you want to waltz in to the council with half the keys already, nothing is stopping you. I can recall when I beta tested the game, getting through probably half of the dungeons before I once stepped foot into town. If you don't go out of your way to ensure you see every last board on the map, it is possible to miss some.

Whenever players bring Eric to the castle and discover how to get past its locked doors, the council is ready to provide the rest of the story. Eric's arrival was the council's own doing. In their search for a way to defeat Daedalus, they uncovered a prophecy stating that when Dagda was in peril, an outsider from a distant land would arrive to save them. While the council's attempts at learning magic have been slow, by combining their efforts they attempted to summon Eric directly to the castle. Lucky break for him that he materialized in a cave! Their hope is that he is the one capable of fulfilling the prophecy.

Eric is an optimistic character, and takes the news of his summoning rather well. He certainly doesn't see himself as a hero or adventurer, yet is immediately sympathetic to the plight of the Dagdians. He's also enough of a realist to know that he will not be heading home unless he can accomplish the mission thrust upon him. He never complains about the job, only dutifully getting to work. By the end of the game, his adventuring skills are indisputable, though some hints of that can be found in his behavior early on.

Amusingly, when entering Virgil's home there's an unlocked room filled with ammo and gems to Hoover up before players speak to him. Hewer connivingly checks for such a scenario, slightly tweaking Virgil's dialog based on whether or not the player has "helped themselves" or not. (It's all good, he was going to give them away anyway). Small moments like this add a bit of humor to a game that when you focus on the story, would otherwise be kind of bleak.

You'll find villagers mourning for the neighbors that were just on the border when the cataclysm cut Dagda off from the rest of the world. Crumbled buildings that teetered on the edge of the void and fell into nothingness. The remains of a young adventurer that attempted to take on the obelisk can be found, as can a matching mother in town asking if you've seen her son who set out and hasn't returned. Survivors gather around a now almost dried up pond, rationing what little water remains. Lives have been lost, and those that live on have been heavily disrupted. Even the council studying magic was originally nothing more than a governing body.

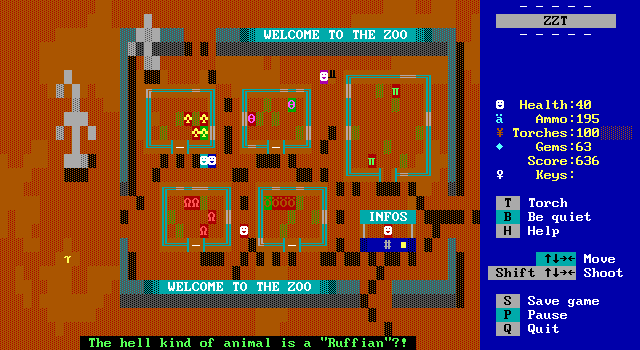

There's even a struggling zoo which exists entirely to crack various jokes. It's struggling from the lack of resources as well as the more unusual problem that all the beasts they have in captivity can now be found just wandering the wasteland. Some people can't catch a break.

Hewer's bits of humor pair well with the silly energy of the original ZZT worlds, and serve as a reminder that for all the people have suffered, at least they have hope. It's a game with its fair share of references to the classics, with more than a few familiar gags and iconography easily recognized by longtime ZZTers. If you're in the know, they'll get a knowing nod. If you're not, you'll get a chuckle. Everything is approachable, with no prior reading required in order to appreciate the humor.

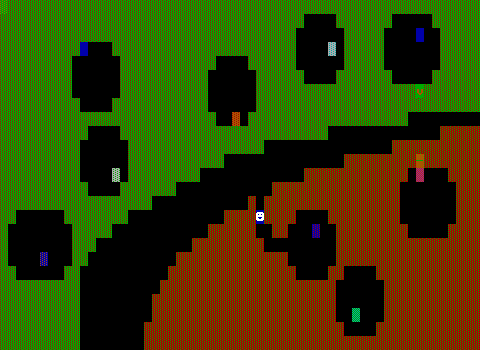

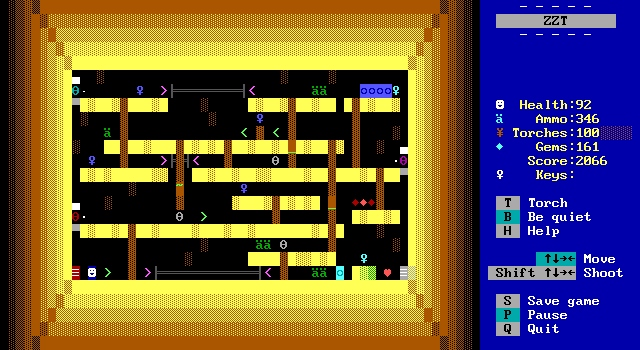

Once Eric obtains all the keys necessary to enter the obelisk, one final challenge awaits him. Upon entering, players are locked inside, forced to confront Daedalus or die trying. This ascent is longer than any of the game's previous levels, with a number of intermission boards as well that feature Daedalus warning Eric to leave now if he wants to live. This is the first time players actually hear Daedalus speaking, bringing him from being a distant threat to one drawing ever closer. It's a helpful addition that shows off Daedalus's personality as he goes from warnings, to suggesting Eric become his apprentice, to the realization that there's going to be a confrontation with boasts about his immeasurable power. It makes that final battle much more interesting than just "shoot the bad wizard" that it could have otherwise been if Daedalus was just a boogeyman to get the game rolling rather than a more fleshed-out antagonist.

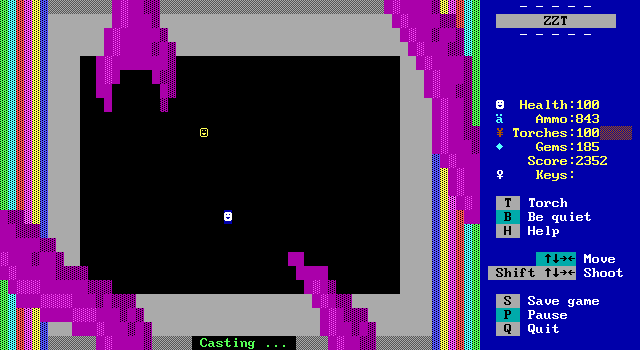

In a real moment of genius, Hewer saves one last mechanic for the final level. He shuts off gravity, causing the player and enemies to float around the room. An effect accomplished by designing a dungeon screen as normal, and then... not placing any invisible water to restrict movement. After playing the game for so long, it actually works, and feels very different from what's come before it despite hardly being the most "unique" gameplay in ZZT.

The climax oddly does take the form of a traditional ZZT boss fight, getting rid of the sideways view. It's honestly not what I expected, especially since Hewer had shown by this point a few ways a boss battle could be implemented. While the format chosen is tried and true, Hewer is just as capable of coming up with some creative mechanics for the battle. Don't expect a run-and-gun slog here. Daedalus has a number of magical attacks that will surprise the player, and the maximum health limit of 100 ensures that the fight isn't a one-sided affair that can be won by cashing out all the gems that have been collected..

Overall, Daedalus' Obelisk makes for a great hour or so of ZZT. The bite-sized dungeons mean new concepts are introduced rapidly, quickly learned, and quickly moved on from, never overstaying their welcome. The open world structure incentivizes exploration, encourages players to search not just for dungeons, but secrets, mini games, and helpful information from NPCs as well. Generous health restoring services make it easy to play any level from full health, while the less patient or more experience can opt to risk getting through more than one dungeon before turning back.

The unique engine-less platforming makes for a ZZT world with little comparison. In fact, when it was released, Daedalus' Obelisk was the only readily available world to do such a thing. Later preservation efforts uncovered a number of worlds by Graham Peet which were doing something similar as far back as 1997, decades prior to Obelisk. These games (which quickly became beloved once discovered) are the closest thing out there to Obelisk. Though even these aren't quite a match, as they opt for text instead of water, preventing players from being able to shoot at and be shot from above. While Peet's forays are definitely worth your time as well, they are very much ZZT worlds from the 90s making players find every last treasure to be able to see the entire game, while stuffing many of those treasures in very well hidden rooms or giving players only one attempt at grabbing them. Daedalus' Obelisk delivers a smoother experience.

So if you're looking for something that exemplifies ZZTers love of finding new ways to combine old ideas, a rather unusual form of gameplay that surpasses expectations, and does so with a level of simplicity that that makes it effortless to pick up an play regardless of ZZT knowledge, Daedalus' Obelisk is your game. It's easily one of my favorites of the modern day ZZT community, and one whose charms and challenges make it a great game to play again and again.