What a glaring omission! For as long as I have been a part of the ZZT community, Barjesse's 1996 game Nightmare, has been considered ZZT's definitive puzzle game. With many going so far as to consider it one of the best ZZT worlds ever created. Hardly forgotten to time, its z2-era reviews never dared to have a naysayer give it a rating lower than a four out of five, giving it some of highest marks on record for a game with multiple reviews. This was a world I was introduced to as a child from just a random ZZT website hosting copies of a dozen or two of the creator's favorite games. It's a game that was radically different from the idea of a puzzle world in 1996, and one whose uniqueness left it with a well-deserved legacy of being an essential play for any ZZTer.

And yet, while one day browsing the list of featured worlds to maybe find something suitable to stream or investigate for a Closer Look, that between Nexus III and NO!, there was a glaring mistake. Nightmare was nowhere to be seen!

Having revisited so many worlds over the past (too many) years has done a number on my perception of what ZZT's past was actually like. Often I find myself revisiting the greats, both by community standards as well as my own tastes as an adolescent, only to realize that while the significance and influence of these worlds was undeniable, to an older audience, a game's flaws often become both blatant and numerous. Poor Sivion has become the go to example of a world where the hype and reality stopped lining up years ago, but it's not alone. Award-winning titles like 4, Dark Soul, and Fabrication have taught me that the purple key icon is less a promise of quality and more a promise of being interesting.

But Nightmare? Somehow this game was passed on by for the (Classic) Game of the Month Award that would have been a no-brainer at the turn of the century. Not quite as old z2 forum threads suggest the game only in passing for the Featured Game awards that succeeded the GotM. I had even revisited it myself at the end of 2016, finally completing the game for the first time, where I was left impressed at how long it took to get through and how well it still held up.

In preparation for this review, I opted to play through it again on stream in a two part series that only validated my belief that the game was a critical omission from the Featured Worlds list.

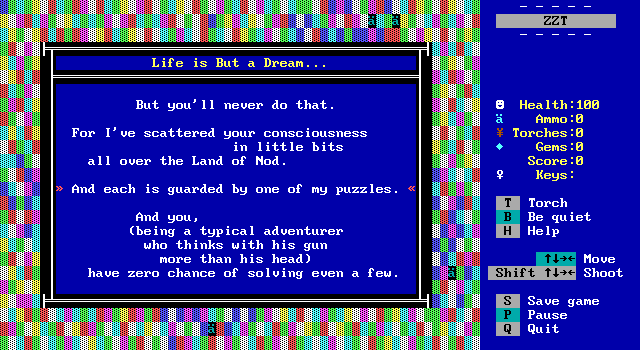

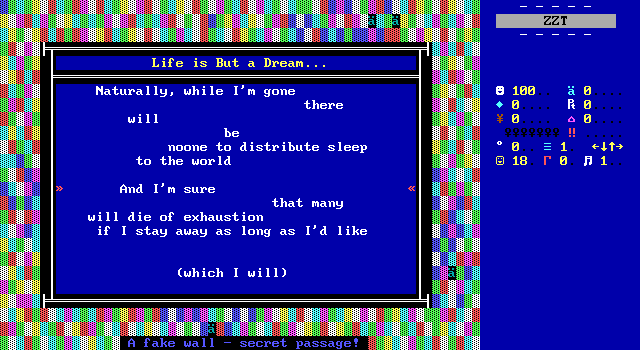

On the basic level, Nightmare is a puzzle game in which the player has to explore the dreamworld of Nod to find the missing pieces of their consciousness. These pieces have been stolen by the Sandman, who, tired of his never-ending job of putting people to sleep has concocted a plot to trap you in Nod so that he can take a lengthy vacation. By collecting all these pieces scattered throughout Nod the player can awaken themselves and force the Sandman to return to Nod.

The stakes are even higher than they may seem as it's not just your life on the line. The Sandman admits that while he's away nobody will be able to sleep, and if they should happen to perish from exhaustion, then so be it. Yes, this is in fact an incredibly literal read of the ZZT world archetype of "wake up and save the world".

The Sandman knows the player can break free, but he isn't worried in the least. He has two aces up his sleeve to ensure that the player has no hope of ever waking up. Nightmare boasts a whopping thirteen pieces of consciousness to collect. If just one of these pieces is unobtainable for the player, then the Sandman's victory is guaranteed.

To make things worse for our typical adventurer, these pieces of consciousness are protected not by monsters, but by puzzles. The player's only weapon in Nightmare is their own brain, and if they can't master it, then it's going to be nighty-night for the would-be hero.

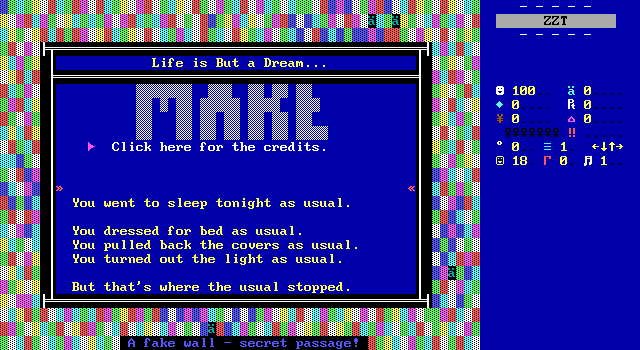

ZZT worlds with macguffins to collect began with five purple keys all the way back in Town, with many authors aiming to follow the pattern it sets struggling to come up with enough content to justify even that many keys. Barjesse has no trouble packing the game with enough puzzles to solve, awarding players a steady drip-feed of individual pieces, represented by letters, that when united spell the word CONSCIOUSNESS.

That's thirteen pieces in a medium that so rarely asks for more than five. The only way you'll top that is by changing the nature of collection entirely with something like Tseng's Gem Hunter series.

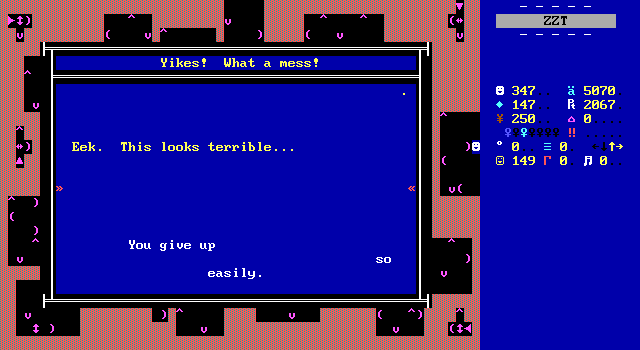

As if the number of pieces to collect wasn't daunting enough, the Sandman raises a very good point about those that were playing ZZT games in the mid-1990s. Adventurers think with their gun far more than their head. The challenge is presented to players as a task that they are incapable of completing. Your job is to prove the Sandman wrong, but as the multiple z2 reviews which confess not completing the game or struggling for days with it, the Sandman truly has the upper hand here.

Those who accept the challenge rather than giving up immediately must go on a journey through Nod which will bring them up against sixteen different puzzles. These puzzles are almost entirely unique, with Barjesse rarely repeating himself. Even in those few cases, there's always some difference between each variation.

In the greater scope of ZZT worlds, Nightmare's puzzles are a bit more derivative. Plenty of the expected classics make an appearance, including slider puzzles, transporter mazes, and City-esque boards with robots to steer in player inaccessible spaces. Long time ZZTers can get a read on such boards quickly, while those new to the program are in for a whirlwind tour of what for most ZZT games is a side-show suddenly becoming the main attraction.

Those who are worried about having seen much of what Nightmare offers in other worlds have no need to fret. Even with these familiar challenges, Barjesse has a knack for designing implementations of these puzzles in ways that still remain engaging and fun even to those that feel they've seen it all before.

For one example of Barjesse making a common puzzle worth experiencing again, his slider puzzle board is a great starting point. The room is broken into several discrete slider puzzles rather than overwhelming players with a larger more full-sized machination. The approach taken here allows players to get through it gradually, with confidence that they haven't put the game into an unwinnable state whenever they reach the entrance to the next chamber.

Most slider puzzles of considerable size are extremely demoralizing, constantly inducing anxiety that you've already made a mistake without realizing. Then when you do finally catch on, suddenly it becomes clear that you lost a significant amount of progress. Barjesse's micro-puzzles provide natural checkpoints. Each exit gives the player a boost to their confidence that they can make it through these things, especially without the fear that at any moment the rug may be pulled out from underneath them.

A few of the puzzles do suffer somewhat: either due to ZZT's limitations or Barjesse's original ideas not always being on the same level of quality as Nightmare's more impressive contraptions. This game is more than twenty-five years old now, holding up strong, though a few cracks may show up here and there.

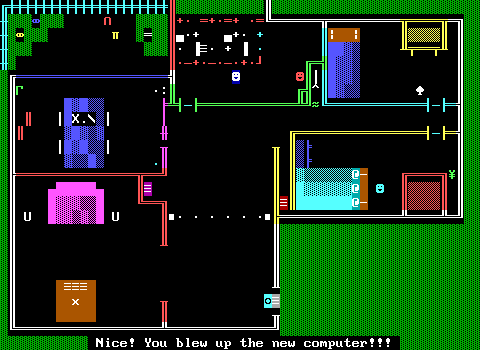

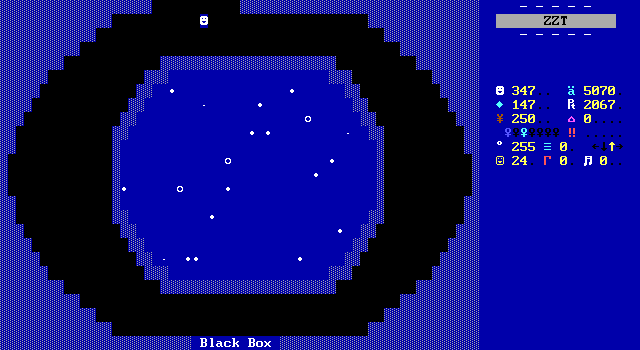

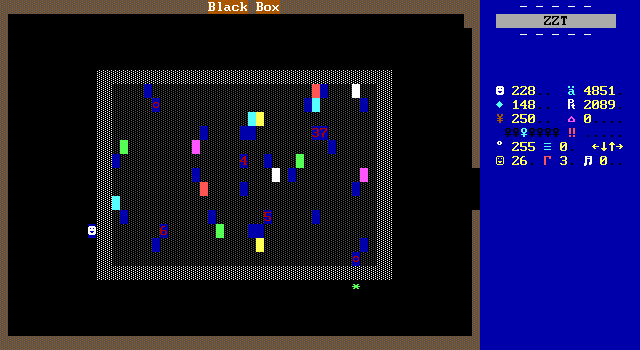

One of the repeating puzzle types the "Black Box" that comes in a regular and "super" form. The super variant shown above requires blindly shooting into a water-bordered area of the board hoping that your bullet deflects off of invisible ricochets within and strikes one of numerous targets. The intent here is for players to slowly unravel where the ricochets are and then to use that information to shoot the targets appropriately.

In practice, the player is given thousands of ammo at the start of the game (provided they read the opening rather than skipping it). For puzzles like this that require a gun after all, the intended method of solving it and the realistic way that everyone else will solve it ruin Barjesse's plan. The puzzle becomes an exercise in wrapping around the box and firing from every possible position. It's not the most exciting approach, but even if the player was to try and minimize their shots, they'll have a hard time figuring out the internals running all over the place shooting in no particular pattern rather than going slowly and methodically.

The regular variant makes its interior visible, instead asking players to hit its targets in a specific order. Both of these can be solved with the brute force approach of shooting every possible spot and making a note of which ones hit targets, but in the case of the regular black box players are able to use their brain more than their gun. This version lets the player analyze the interior and work backwards to find the correct location to shoot from.

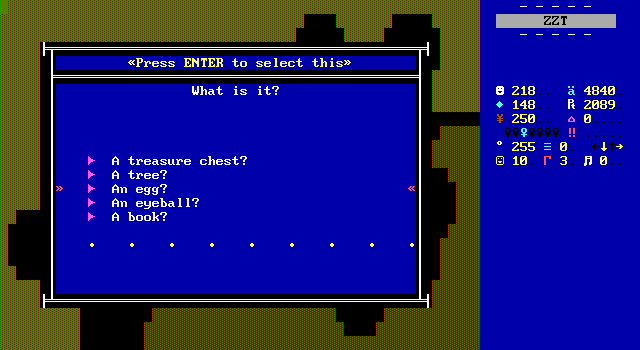

The question prompts that appear throughout the game also feel a bit weak, though Barjesse can't be blamed in this instance. With no text entry in ZZT, the riddles and trivia of Nightmare found on two boards are open to being solved through pure stubbornness. It's possible to guess your way to success, reloading after any incorrect answers. Even if you're playing in good faith, merely having a list of options lets players stop and consider the logic of any individual answer that could make it the correct one, reducing the difficulty of the more sensible riddles, while causing frustration with some of the quirkier ones. All the same, I suspect I wouldn't have beaten this game if I did have to actually come up with my own answers.

Even the least satisfying riddle in Nightmare is still a step up from some of them out there.

On average though, the game's puzzles are enjoyable much more often than no. The only real disappointment to be had comes from the game having such a strong legacy within the ZZT community that you'll expect the game to be full of stumpers that will keep you occupied for hours. Alas, most puzzles are far easier than Nightmare's reputation would lead you to believe. The hours and afternoons spent trying to make progress as a youth won't give the average player today much trouble at all. If you're looking for some ZZT puzzles that will leave you pounding your head against the wall, a game like Sixteen Easy Pieces is likely what you're after. (But bear in mind, you do need a very solid understanding of how ZZT's elements behave to complete it.)

What Nightmare can still offer players that more modern puzzles games including Sixteen Easy Pieces and the more gentle Ana do not, is in its variety. Flimsy's masterpiece is essentially one kind of puzzle taken to unprecedented extremes, with Ana designed around four different puzzle types that slowly increase in difficulty.

With Nightmare you can expect to find:

- Mazes with buttons to shift the walls

- Slider puzzles with objects to cause faux boulders/sliders to surprise you with their behavior

- Black boxes with targets to figure out how to hit

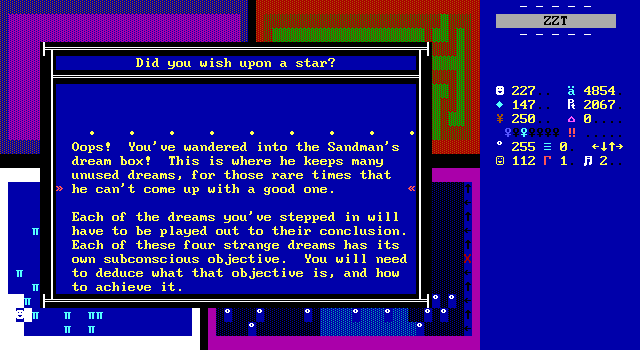

- "The dream box", a series of four mini-dreams that players have to figure out what needs to be done for them to be considered completed

- Mazes with phony breakable walls that shoot back

- Slider puzzles that would make Sweeney and Janson proud

- Trivia covering topics ranging from computer terminology to unscrambling jumbled words, to paying close attention to details in the room

- Determining the time based on the gongs of a clock

- Spinning arrows to guide bullets shot from a cannon to reach different targets

- Finding your way through a maze with nearly-invisible conveyors limits your options

- A series of riddles that avoids the riddle of the Sphinx and other too well-known to be effective questions

- Obtaining even tinier pieces of consciousness in a maze whose floors and walls constantly shift

- A transporter maze that then asks players to find a way to push boulders to re-route where the transporters lead

It's a veritable smorgasbord of ideas that keeps the game from ever feeling stagnant. Best of all, the non-linear structure means that when a puzzle does get to you, it's easy to turn around and try a different screen. Eventually, all puzzles do need to be solved, as the few that don't offer rewards still open up access to others that do. That sort of design can be a bit much for the younger audience the game was originally released to, but a fresh start is likely all it will take for those reading this today to find it in them to conquer the previously unconquerable.

The puzzles, undoubtedly, are what make Nightmare a great game, but the experience becomes an unforgettable one thanks to the way Barjesse writes the villainous Sandman character. The Sandman never actually meets the game's unnamed protagonist, nor is he ever even depicted in the few more cinematic screens. The Sandman exists in Nightmare entirely as an eerie presence that will stick with you for the rest of your days.

Much of this comes from a very simple technique that Barjesse uses to phenomenal effect. The sandman is given a way of speaking with frequently long pauses mid-sentence. This irregular form of conversation is matched in presentation where the pauses are not an influx of commas, ellipses, and line-breaks. Extra spaces are all it takes to pull off the unmistakable way of speaking the Sandman has, with his every other word appearing at seemingly random intervals. One gets the sense that his speech is almost poetic, yet there is no clear structure to be found.

Players are immediately introduced to the Sandman in the opening window, following a short blurb that sets up the tone for the game. Its writing, ends up being one of the game's strongest components, taking a serious tone when most ZZT games were focused on being... let's say zany, with more serious works few and far between. Especially serious games that weren't trying to be immersive role-playing experiences.

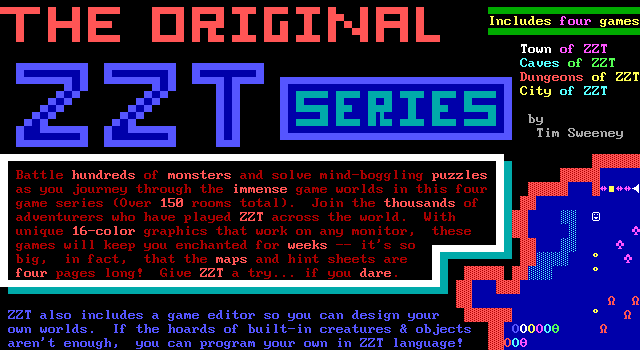

As a game released in the AOL-era of ZZT, Nightmare has an air of quality to it that few could hope to compete with. When compared to the seemingly infinite number of ZZT games filled with references to Barney, Beavis and Butthead, and Ren and Stimpy that tended to appeal towards more low-brow humor, it's no wonder Barjesse's old AOL-hosted webpage describes the game as "a thinker's adventure".

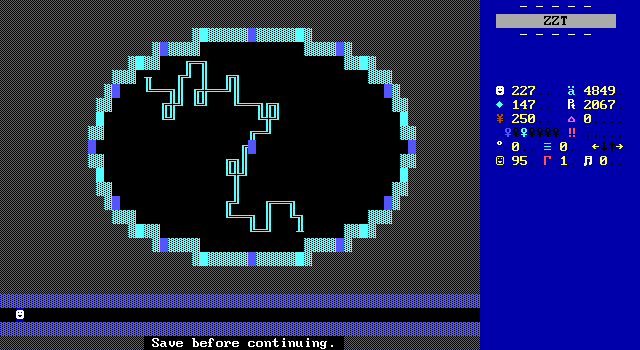

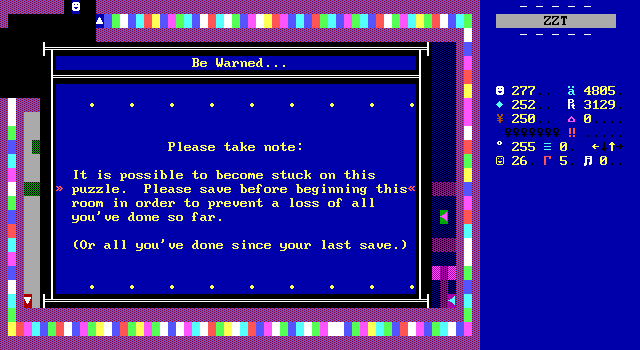

Regardless of how much of a thinker you may be, a word of caution should be given to those who think they are up to the Sandman's challenge: Being a game as old as Nightmare is, the game relies heavily on your ability to save and load at-will. It is possible to render some puzzles unwinnable, and as most puzzles have to be completed to obtain a piece of your consciousness or to reach other puzzles with said pieces, you should always create a safety safe before attempting any puzzle. More often than not Barjesse himself will include a disclaimer of some sort in the puzzle's introduction to really drive home that failing to make such a save may result in significant progress being lost.

The Super Black Box puzzle (that is, the one without numbered targets) is an unfortunate victim of the game's only known programming error. Upon completing the puzzle, players have to then catch the piece of consciousness that is their reward. If the piece manages to make a full lap, long story short, they will be unable to ever grab it.

The only other things to watch out for tend to be the usual ZZT puzzle mistakes. Sliders accidentally blocking off critical paths, moving boulders into corners and being unable to use them for their intended purpose, that sort of thing. Really it's no worse than in adventure/puzzle hybrids like Town, just with so many possible puzzles to make mistakes in, the odds are at some point you will screw up. Be smart about your saving, and you'll be much more willing to try and try again as needed.

Nightmare also has a minor claim to fame in being a rare example of a game that uses the technique of flag management known as "piggybacking". With only ten flags available for thirteen letters to collect, Barjesse instead combines them into a composite flags, using the name as a crude way to track everything. Picking up the first "O" will set a flag "xOxx". Grabbing an "N" and then "C" will update the flag to "xONx" and "CONx" respectively. This requires a lot of extra code to handle all possible combinations of letters that may have been collected in each group before grabbing another, but it's a great example of the level of care given to the game.

This could have been a game with thirteen purple keys, or Barjesse could have gone with a simple "one piece at a time" rule, demanding players that find a letter immediately return to the starting hub to add them to the list. These solutions, while valid, would certainly have made for a lesser experience. Barjesse realizes the value in the player's time, not wanting the high of solving a screen to then be ruined by the realization that a lengthy return to the start is needed only to venture right back out again to head to the next puzzle.

In a few instances, Barjesse was even kind enough to streamline the backtracking that's inevitable for any game designed with a hub and spoke layout as this one is. A few puzzles, once solved, will have some objects lay down the red carpet for players, gleefully creating a direct connection from one end of the board to the other where there was none previously. This is so much nicer than having to trip over yourself to avoid accidentally pushing a slider or boulder in an already solved puzzle in such a way that your path becomes obstructed.

At other times, Barjesse takes it a step further. Any straight line of boards without any alternate exists themselves will take advantage of ZZT's ability to connect boards arbitrarily. Solving the last puzzle and attempting to leave the way you came will bypass the previous boards entirely, dumping players as far back to the start as possible until there's a board that splits off into another path or they reach the starting point. (Though this can be a bit jarring when you're not yet expecting it!)

The strong reception to Nightmare partially comes from its lack of competition. ZZT itself emphasized puzzles as a core component of gameplay since the very beginning.The Epic MegaGames Summer 1992 Catalog makes sure to mention "mind-boggling puzzles" as well as a few blurbs from registered users praising the need to think while you play.

During the stream, somebody (who I can't find for the life of me now. Yell at me if you know so I can edit their name in!) made the connection that Nightmare is actually rather similar in structure to Town, a read on the game that I had never considered before, and find myself really agreeing with now. The game is open-ended, allowing players to go where they please, just as with Town. Purple keys have been transformed into pieces of consciousness, and while there are far more than five to collect, the board-by-board structure still means players start in the middle and find their way to the outer edges. In Town this reward is saved for reaching the end. Nightmare hands out its pieces like candy, very rarely not congratulating players for solving a puzzle. The game feels like a darker take on the Town experience. It's like Town, but with something amiss everywhere you go. The bright colors replaced with more dull colors or monotonous almost brutalist design instead.

The early trend of capping off the player's search down any particular with a purple key or macguffin of choice didn't really last all that long. It can be seen in the original saga and the next generation of releases for sure. After all, they only had the original worlds to reference for what a ZZT game should be. Over the next few years worlds took a turn towards more linear focused adventures with more narrative elements, often as silly as possible. The days of sending in your high scores were a mere blip in ZZT's history as soon as creators realized they could make anything they wanted and not just something in the image of Sweeney.

You'll find pages and pages of games with the puzzle genre on the Museum that predate Nightmare. Yet nothing comes close to the purity of its design, or the quality of its puzzles. This is especially true for ZZTers specifically looking for a puzzle game that wasn't an adventure with a board or two with some sliders or a transporter maze sprinkled throughout. Games with titles as straightforward as Mazes and Puzzles for the Expert, ZZT Puzzle World, or just Puzzles, tended to be huge letdowns, generally low-quality creations that relied on mazes more than anything else. If you were lucky, you'd get something like Puzzle Land, which while it seemed to have some effort put into it, would be over quickly as the world consisted of so few boards.

Action simply could not be escaped until Nightmare came along. It may have the distinction of being ZZT's first pure puzzle game, and that alone makes it worth checking out. It's bringing a well established genre to ZZT that by 1996 was long long overdue if you cared about quality.

Even in the aftermath of its release, clones and competitors were nowhere to be found. To this day, Nightmare really has no clear successor or rival. There's no ZZT game that sparked debate over whether it or Nightmare was the superior game. There's no, "now that you've finished Nightmare, you've got to check out <X>". Once you've completed Nightmare, you pretty much just have to sulk or move on to those few titles that focus on a small set of puzzle designs, increasing their difficulty as they repeat.

The nearest game that I can find is Dexter's Xod, the start of a brief series consisting of Sokoban, music recognition, and some trivia. It was a successful release, winning a Classic Game of the Month award a year later.

Xod really highlights the uniqueness of Nightmare. Nightmare integrates its puzzles into the world it builds and the story it tells. Xod does what most others would have done, and just assembled a collection of puzzles. The earlier mentioned Ana is able to use its puzzles as part of a story, but still can't manage to directly make them a part of the world which players explore. Neither game is able to provide an explanation as for why these puzzles are there.

Barjesse fills the game with reason, even managing to avoid the cop-out justification that since this is a dream world, anything can happen. Players get to explore the Sandman's workshop, clean up "dream glitches" (the points in dreams where you realize you're in a dream), venture through the instability that causes your dreams to abruptly change location, and push around blocks of sleep that are used to make people lose consciousness. While not everything is explained so tidily, it's apparent that Barjesse took full advantage of the setting and story he came up with, and used that to dress up his puzzles much in the same way that a good ZZT action game will offer alternative names to lions and tigers when players are fighting space aliens or trolls.

There's a level of polish seen here that few ZZT worlds had managed to reach by this point. It's very easy for puzzles to feel cruel to players rather than satisfying to solve. Barjesse is able to use the Sandman's echoing voice as a way to taunt the player without tormenting them. Yet even the Sandman isn't negative every time. He'll doubt your abilities, and offer you the chance to prove him wrong sure, but at other times he'll also provide some soft encouragement, telling players not to give up before they even begin just because a puzzle looks too hard.

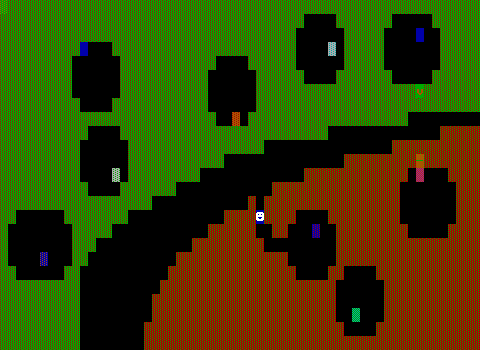

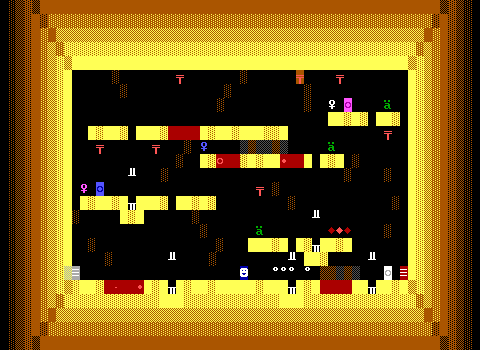

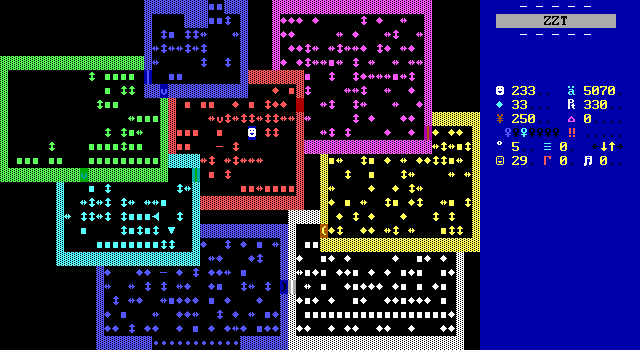

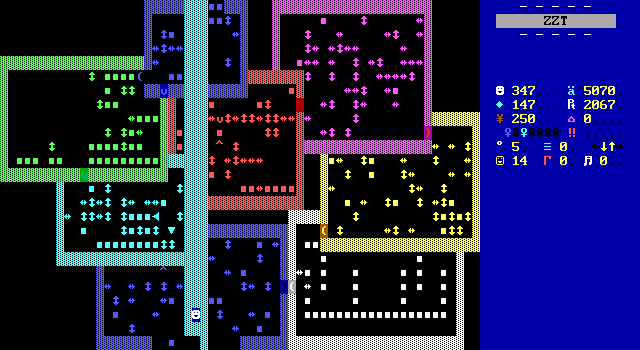

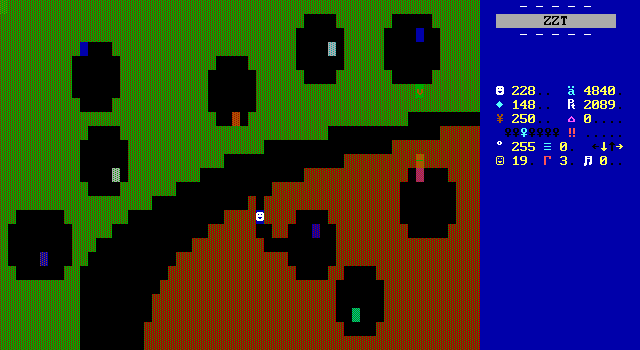

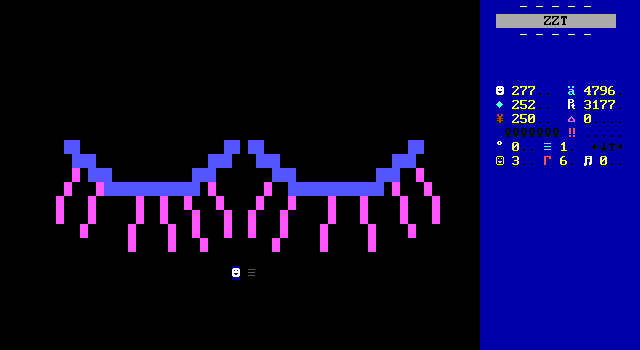

Nightmare has a look very different from anything else around at the time. It's recent enough (read: under thirty) that it makes extensive use of Super Tool Kit's extended palette offering, doing far more than just making the walls dark. The game shifts in appearance wildly, with muted colors on one screen, and hyper saturated colors on the next. The land of Nod can look however it wants. In the world of dreams there are no rules, giving Barjesse the freedom to make his walls dark red on dark green, bright red on dark cyan, dark gray on brown. When so many others were using the extra colors afforded by STK to choose colors that made more sense, Barjesse was more interested in using combinations not often seen. To this day, it's hard to find games with a similar look.

The boards also stylize themselves after older ZZT worlds: screens flood-filled with normal walls that are then carved into shapes ever so slightly irregular. The human touch compared to the perfect lines and centering offered in later years via external editors.

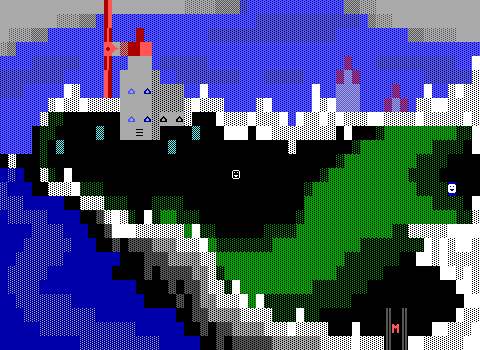

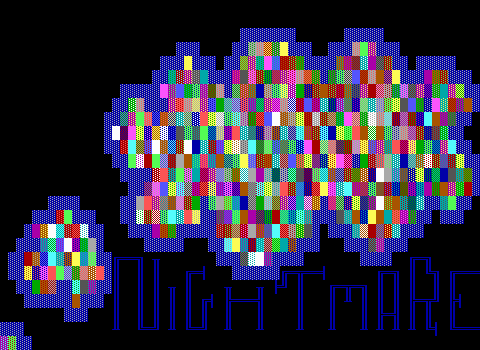

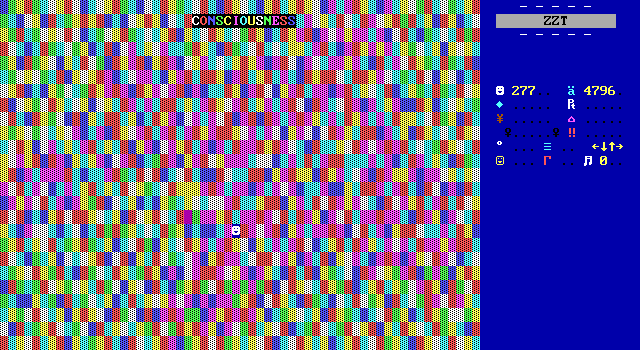

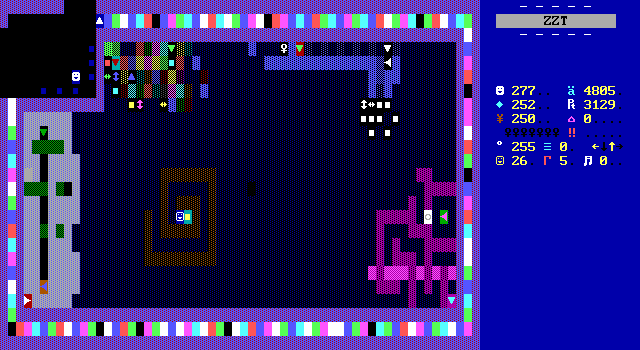

There's plenty of wow-factor to be had as well in both the game's earliest and final moments. Its title screen is a chaotic mess of shifting colors with every one staggered and cycling through solid, normal, breakable, and water. The chaos continues even in the text showing the game's name, shifting the colors of the line walls its composed of with a touch of randomness for which color to choose next. You can get lost just watching the fluctuations on the title screen.

The opening then uses the same technique with a pattern of walls and fakes that hardly looks anything like Town's starting hub despite sharing the same functionality. The ZZT Encyclopedia showcases a technique where by detonating a field of bombs on the title screen and opening the editor when they're mid-explosion. The editor will open with this random pattern of breakables frozen in place. (You can extend this by changing them into walls or fakes or whatever you like.) I've always assumed this was how Barjesse made this board, though I can't be certain.

Navigating a board of random colors where the walls and the floors look identical, should be a recipe for disaster. Barjesse's board is surprisingly easy to get through, and it took me all these years to realize why.

Look closely and you'll realize that the walls do not use blue while the floors do. This is enough to keep the intended effect of swirling colors while keeping players from constantly bumping into the irregular layout of the walls that form the hub's contours. To me, this is an unmistakable sign of Barjesse's commitment towards keeping players from getting frustrated at anything that isn't a puzzle.

As for the game's ending... (Don't worry. No spoilers here.)

The ending also makes use of color cycling, taking what would be a short animation played out using invisible walls, and ramping up the psychedelics of it. The rest of the board is set in total darkness, which is a bit of a blessing as I suspect the flashing might be a bit much were it not limited to so few visible tiles on screen. The animation is simple, yet still pushing ZZT forward when the game was released.

Nightmare is a game that can both turn heads as well as get them scratched. The ZZT community has confidently been calling it a must-play from the very beginning, and it doesn't look like that praise has faded in the intervening years. For puzzle fans, this is still one of the best of the best that ZZT has to offer, a pillar that stood uncontested for ages. For those that think with their guns, Nightmare is an exception to the norm that remains more than capable of converting those non-believers that demand their ZZT be more twitchy. For those in it for the narrative, things might not develop all that much over the course of the game, yet it's easy to appreciate Barjesse's ability to integrate a story at all into a genre usually utterly devoid of one. Those who played it at a young age will never forget the Sandman's mocking words, the devious riddles, and the seemingly impossible tasks that lay before them.

Whether you're interested in key moments in ZZT's history, dream-like worlds, or just looking for a chance to do something other than shoot for a change, Nightmare is undoubtedly a first-class world to journey through. It showcases the pinnacle of design for its day, while holding up remarkably well today.

Don't sleep on it.