Sixteen Easy Pieces was released in 2005 by Flimsy Parkins and like the vast majority of ZZT titles released halfway through the 00s, was promptly forgotten. It has a single review by Commodore praising its ingenuity, and also a ZZT preview video by Commodore as well that just shows some footage of the game.

Despite the near invisibility of the title, Sixteen Easy Pieces is quite clearly of the best puzzle games I have ever played, both within and outside of ZZT. If you have the slightest interest in puzzles, I cannot recommend that you play this game enough.

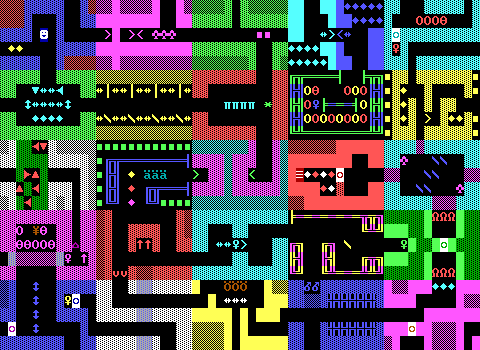

What Flimsy has done here is taken ZZT at its most basic, and turned it into something that at first glance may look like a visual mess. However, as you play the game and begin to put things together and understand what's being done, you'll find that the game has an incredible amount of thought put into every tile. It is not a random assortment of blocks, but an intricate and delicate piece of machinery. It is clockwork that could only have been created by somebody with the steadiest of hands.

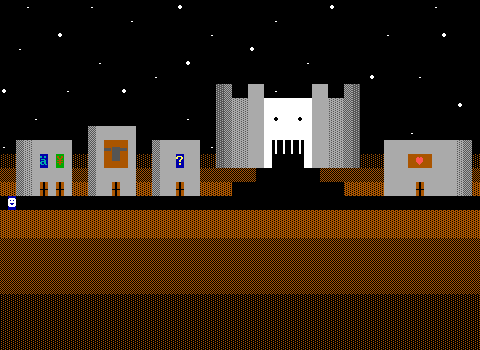

Sixteen Easy Pieces is a series of 8 "levels", consisting of a single board, where each divided into (roughly) equally sized pieces, beginning with 2x2 and growing in size all the way to 9x9. There is no story, and no motivation for the player other than to see how the next puzzle can top the current one. All motivation comes from you, sitting in your chair, deciding that it must be possible to get through this and the immense satisfaction upon doing so.

All you need to do is get to the exit. To do that you'll need to open doors. To do that you'll need to pick up keys. To do that you'll need to work transporters, sliders, boulders, pushers, forests, blinkwalls, spinning guns, bears, lions, bombs, and more to do your bidding. Mistakes are rarely fatal, but instead lead to the player being trapped in a small section of the level and unable to proceed. You'll need to save very frequently, and with new filenames. You'll run into situations where you get 90% through a puzzle and realize because you didn't open a path at the start of the level you need to start from the beginning, and you won't be upset about this. You will press on.

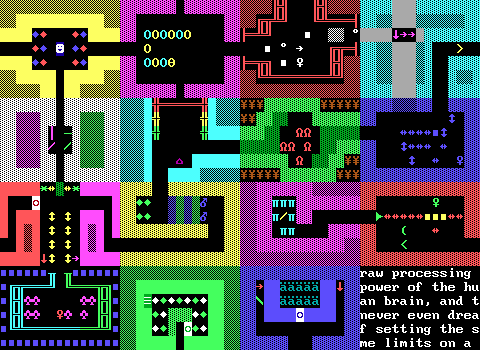

The game trains you to think in ways you wouldn't in other ZZT games. You'll find yourself in situations where there are two mutually exclusive paths, but both are required, and spend ages poring through the board only to find the one trick that makes it actually possible. You will chase red herrings, trying to find a way to move bears to block transporters, or try to desync the rays of a row of blinkwalls in order to let the player make the trip across both ways. You will open up a paint program and draw your path, marking which pieces can be accessed from which. You will find yourself at the mercy of simple ZZT mechanics Tim Sweeney settled on in 1991. Did you know stars run away from the player when they're energized? Or that the breakable walls produced from a bomb can for those few cycles where they exist alter the destination of a transporter? You'll learn.

Sixteen Easy Pieces will make you an expert on the mechanics of transporters, and find out ways to use stars, centipedes, blink wall rays, and explosions to temporarily redirect them. You'll find yourself scanning over each level _piecing_ together ways it might be possible to reroute them without knowing if you'll even need to. The history of ZZT Games is one of trying to get away from these basic elements, and wow the player with clever code and objects. Flimsy was able to embrace the tools we were given and take a path not taken for ZZT design, celebrating not its scripting language that made ZZT famous, but the forgotten components that need no code. The game is an ode to the unloved mechanics that the ZZT community tried to "outgrow" a need for, and draws you into an alternate world where the heart of ZZT is in its puzzles above all else.

"Puzzle" is one of the oldest genres for ZZT games. The original worlds are loaded with them, and many titles over the years have been focused on them such as Barjesse's Nightmare, Toucan's Pop!, or MadTom's Burglar!. What Flimsy managed here, feels more pure than any of these. The components are nothing more than ZZT's standard elements.

Flimsy Parkins managed to take these incredibly familiar components of a ZZT world and find ways to make them feel fresh again. Each of the pieces that make up a level could be mistaken as being portions of early 90s ZZT worlds on their own, but it's the way they connect and interact with each other that make them feel like more than the sum of their parts.

Contrast it to the previously covered Ana, and its puzzles, and you'll see two very different ways of making puzzles in ZZT. Ana liberally uses objects to create puzzles that can't be done with ZZT's standard set of elements, and would frequently recognize mistakes players might make and use objects to repair the damage and allow the player to keep making progress. Flimsy meanwhile demands near perfection. The only mistakes allowed are taking damage from built-in enemies, but even then there's a chance that you'll need some of them to be alive later on.

That style of game design, is usually considered overly punishing, especially to a modern audience (see the change in how Sierra's classic adventure titles are perceived today versus on release), but I think Flimsy pulled it off. I never found myself wanting to stop playing due to a lack of fun. I had to take breaks to let my head clear so I could take a second look when I was stuck and hopefully notice what I had missed. Even then, during these breaks, I'd find myself going back to the game outside of ZZT, looking at screenshots and drawing crude maps in a paint program to figure out what portions of the board were accessible from which pieces. The game becomes a commitment in a way, but one where you'd want nothing more than to see it to the end.

The game actually does contain one object. Its purpose, ironically, is to prevent a bug in ZZT from occurring. It is an imperceptible mark on the game and I am so curious about why it's there. Did Flimsy, who demonstrates an unparalleled knowledge of how ZZT's elements can interact not know how to avoid the bug? Was it so important that the layout of the board be what it is that to remove a centipede or a blinkwall would taint his vision for the game? Or is it just our one chance in this entire game to have a piece of knowledge that Flimsy didn't?

I would also highly suggest that if you do opt to play the game, that you do not take advantage of the walkthrough I wrote for the game, or watch the individual level playthroughs or livestream of the game. Played competently, Sixteen Easy Pieces looks like a performance, but like any performance, it is only through hard work and practice that you'll get to the point where it can become effortless. I've played through the game several times now, and would gladly play it again right now. I (half) joke about speedruns for ZZT worlds, pointing out exploitable bugs or extra keys in these games as speedrun strats, but this one honestly is a fantastic speed game. I would love to see the game completed without having to make any saves. This is one of the few ZZT games where you can genuinely notice that you're improving at the game, both in subsequent playthroughs, as well as realizing the first time you play that you know what you're looking for when trying to figure out the correct path in later levels.

Sixteen Easy Pieces is an exemplary example of good design which to an outside observer is likely inscrutable. Going into it without any ZZT experience should be avoided, but if you've got a grasp of the basic building blocks of ZZT, you're in for an unforgettable experience.