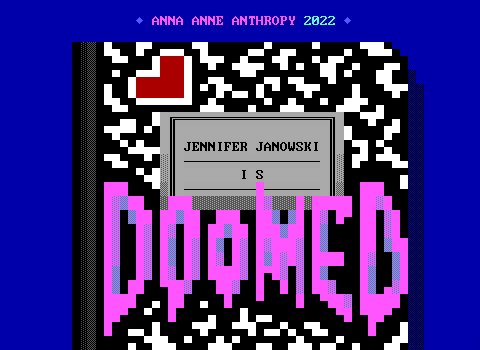

Ancient Times

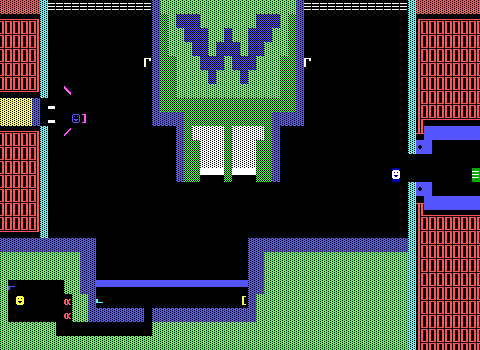

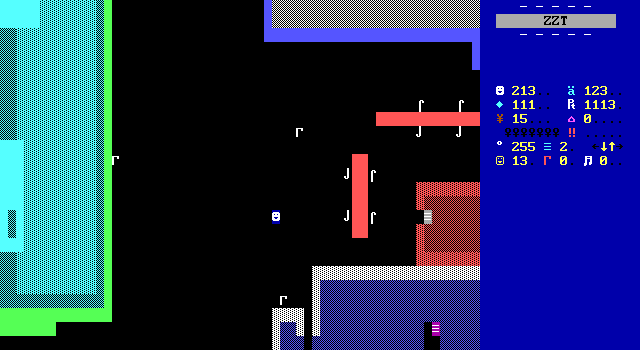

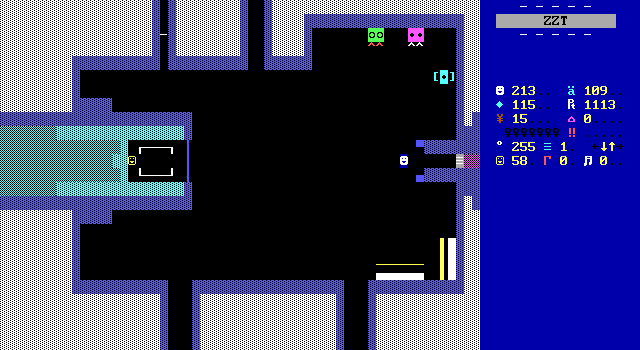

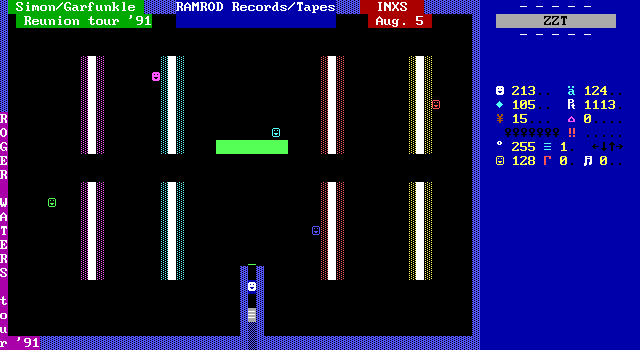

The correct portal to Earth, represents a rather dramatic change in how the game plays. The initial by-the-book ZZT adventure is abandoned the moment the player arrives. The rest of the game takes an approach almost entirely devoid of action and danger. Instead, it turns into a Fuck Around and Find Out game.

This makes sense given where players end up. The ancient city might not seem so long ago to us, but in a game where the present year has a fifth digit, it's certainly a blast from the past for the protagonist.

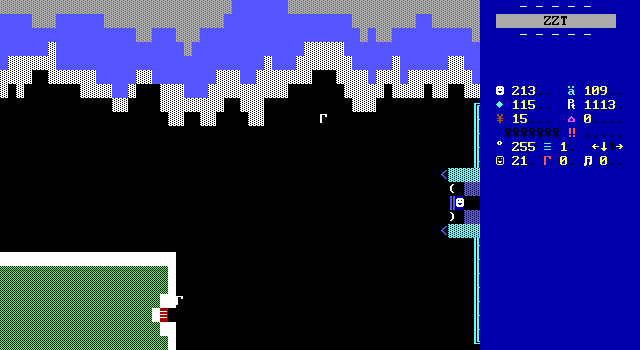

Welcome to 1992.

Welcome to Miami.

The player's goal is pretty much the only thing that remains intact here.

There is something about the setup of a game set (mostly) in present day, but presented as being ancient that really worked well for me. Perhaps its because my own memories of 1992 aren't exactly vivid, having spent most of it being three years old. At the time, I suspect the arrival in 1992 was itself an amusing joke that surprised players, even more-so once they realized that this was indeed the rest of the game.

Going back to 1992 in 2023 though, is a wonderful experience. Hoelle's portrayal of what was most likely present day has itself become a historical artifact. It was just as much a trip to the past for the protagonist as it was to me. What would Hoelle include here, and how would one uncover the meaning of life in a time that for us isn't exactly a go-to year for humanity in its purest form?

Here in the past, players are once again given a rectangular overworld to explore in any manner they wanted, busily searching away for something, with little idea as to what.

1992 is a sharp contrast to the war-torn future, with a huge number of locations to explore, and streets actually populated by Floridians living their day to day lives. It is, certainly by comparison, an age of peace and prosperity. Perhaps Hoelle wanted us to appreciate all the wonderful things we had available to us then.

Your gun suddenly feels a lot less useful. As do your torches when caves are replaced with gas stations and movie theaters where it's considered rude to light such things. US dollars your gems ain't either, but some folks have a hard time resisting gemstones which may make the exchange rate difficult to calculate.

It's impressive in a way that suddenly so much of what the player had acquired becomes useless, and yet that's not entirely true. Your gun will need to be used, just not against lions. The torches will still come in handy as well when dealing with government vaults or a cheap landlord that refuses to spend a dime on electricity for their office.

The currency being so different leads to players having to come up with alternate ways of getting what they want rather than direct payment. Sometimes its gems, sometimes favors. In one instance the player is offered some cash if they agree to sell their seemingly unnecessary gun, leading to a scene similar to the depressing ending of Merbotia, where doing so will lead to an encounter with a gang and being unable to defend yourself, leading to a game over in order to ensure that the player cannot actually acquire cash.

The structure of the game changes to exploring these spaces, gathering information, and making connections with people so that others are willing to give you the time of day. Suddenly, the game to compare this to unexpectedly becomes John Shipley's The Cliff, another game about roaming around a town in search for clues to a mystery. Shipley was clearly a young author, and so the form of progression was a very arbitrary feeling trade sequence of items: giving somebody a cassette in exchange for a newspaper, and then giving that newspaper to a man for a hat, and then giving the hat... etc. etc.

Which to be clear, I absolutely adored. That game was immensely charming and Shipley's works quickly became some of my favorites.

Hoelle though, strikes me as a little older and a little wiser. Progress feels more organic, with players making progress not by finding items, but by discovering new locations. In fact, the game does something startling given its design and quality. Hoelle manages all of this without the use of a single flag in the entire game!

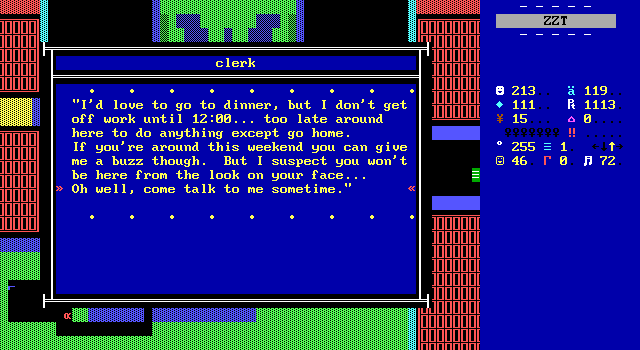

From this point forward, every obstacle the player encounters has to be solved with words. Paying attention to what people say is key to getting anywhere, but the people of the 90s aren't exactly obtuse. Calling this part of the game a puzzle, while technically true, isn't the right way to look at things.

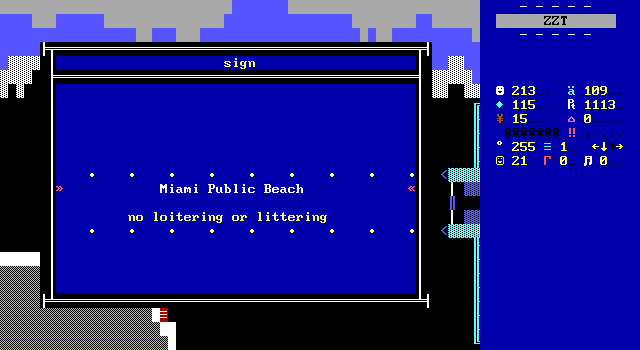

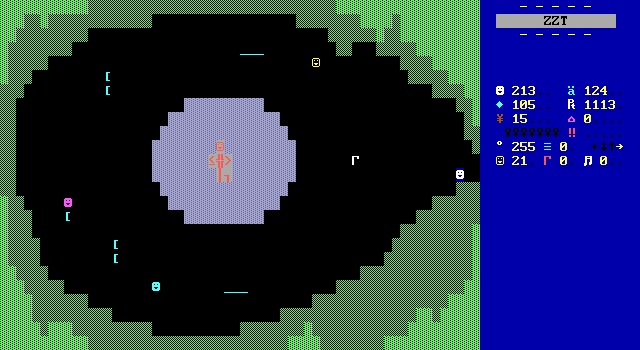

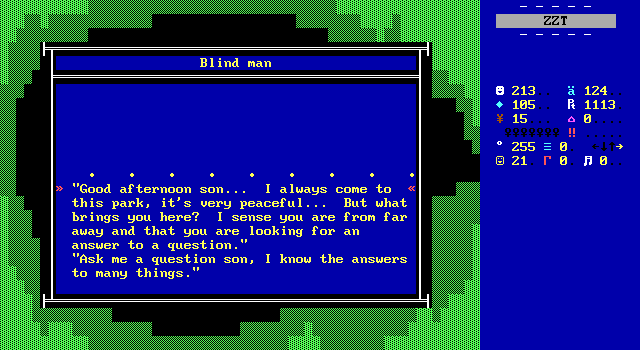

Information is frequently spelled out, with the player's first major lead coming from a blind man located in the park which fittingly placed in the opposite corner from where players arrive. This gives players a lot of opportunity to soak in the environment, curiously poking around the gas station, liquor store, movie theater, restaurant, and more before they'll manage to be able to accomplish much.

The good news is that the world is simply fun to explore, so even when you're not making progress towards your goal of finding the meaning of life, you'll still be having a good time. It's hard not to become excited with each storefront, wondering what relics of the era will be discovered inside.

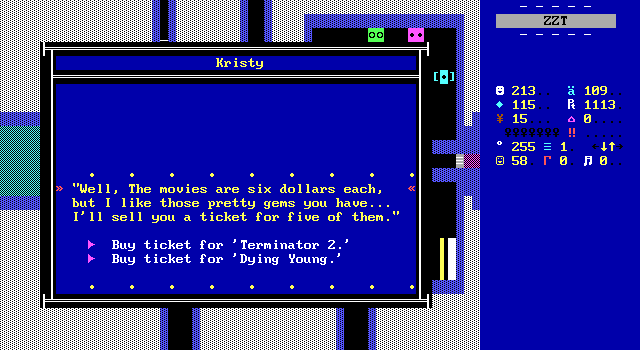

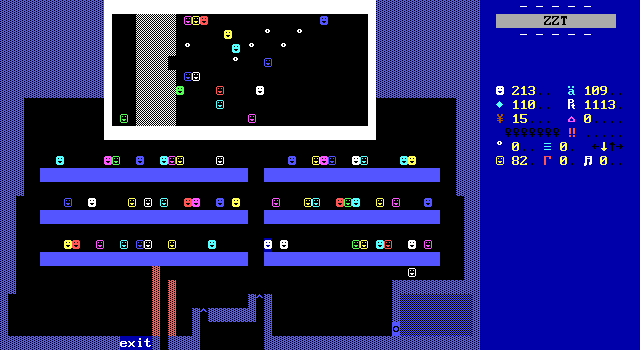

The movie theater is unsurprisingly the most high effort. ZZT movie theaters mean ZZT movies, simple animations to distill films into scenes rivaling 5 Second Films in length.

And wouldn't you know it, Terminator 2 is now in theaters as is Dying Young. And yet, I can only recall one of these films existing. Sorry Julia Roberts.

The movie is simply the terminator moving up and down and shooting wildly into a group of people. Once they're all gone, the movie ends.

Dying Young has been immortalized as well, with Hoelle's opinions really getting through. Honestly seeing his commentary is just as much part of the fun as seeing what got included in the first place, and it's not only the film's dialog. This one ends with your character falling asleep for an hour and then being escorted out by a group of ushers for disturbing everyone with your snoring!

Equally entertaining to seeing what Hoelle found to be the cultural touchstones of 1992, is what things he believed would still be around in 31,289.

It's a pretty short list, but that just makes it more amusing. The movie theater has a few other elements to sell you on 1992. One of which is incredibly funny to me as the protagonist doesn't bat an eye at the cigarette vending machines, only noticing that his favorite brand isn't there. Smoking must really pick up again in 29,000 years.

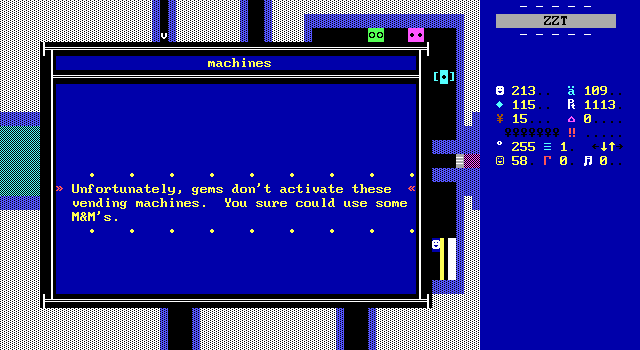

Humanity has managed to keep on producing M&M's though. They're not just recognized, they're crave-able.

Lastly, the lobby has a few arcade machines, with only Pac-Man being recognizable despite not being named. The various "old" forms of entertainment featured throughout the game rarely land with the protagonist who has experienced more exciting things in his own time, yet usually he appreciates the attempts of these ancient humans. Of all things, Pac-Man is strangely entirely unpalatable.

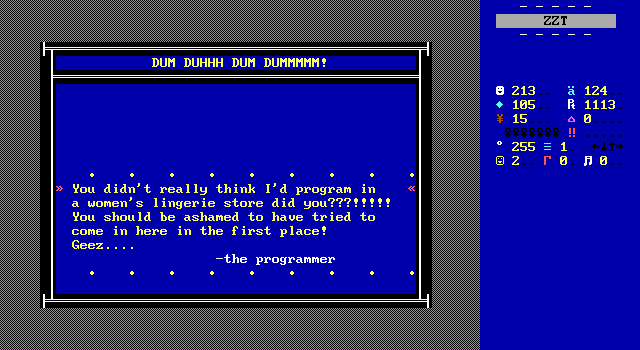

I'd be remiss to not show off the game's lingerie store either. How spicy!

Just kidding! This is the source of the famous scroll which I completely forgot was from this game until I tried going inside.

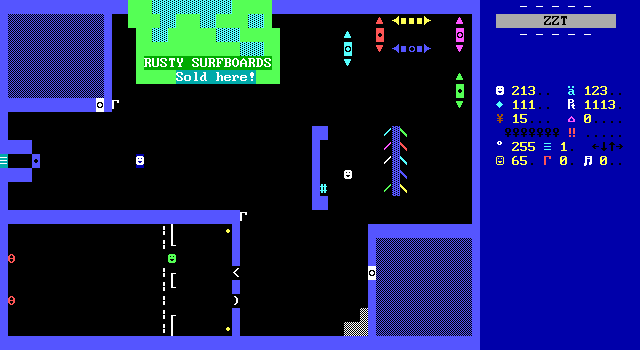

A few locations are actually entirely pointless in terms of game progression. I wouldn't dare complain about this though. Getting to see these banners is great, and Hoelle does a good job of keeping these locations interesting to investigate even when visually they look rather simplistic. In the case of the liquor store, he was even able to surprise me by having a reason to return at the end of the game, using a key to get behind the counter. It's the kind of detail where you wouldn't think it would be a door intended to open, but it allows for different dialog without flags by having the clerk say different things when addressed from either side of the counter.

The game does still fall into some weird stereotypes, which is easily its biggest flaw. You probably won't be surprised to hear that while perusing the rap section of the record store that they note the "strange names" and "vulgar titles". A woman in the park will ask for recommendations for a good "accupuncture-guru-therapist" as well as ask if you're read an article about complex carbohydrates holding Satantic ceremonies in your digestive system". It gives off the vibes that these people are in some way doing something wrong by listening to certain music or caring about their health, then exaggerated into a caricature that is then pointed at as the default personality of any folks with such interests. The ZZT community has certainly come up with far worse than anything here in the years since. It just feels weird to see someone getting worked up over something this trivial.

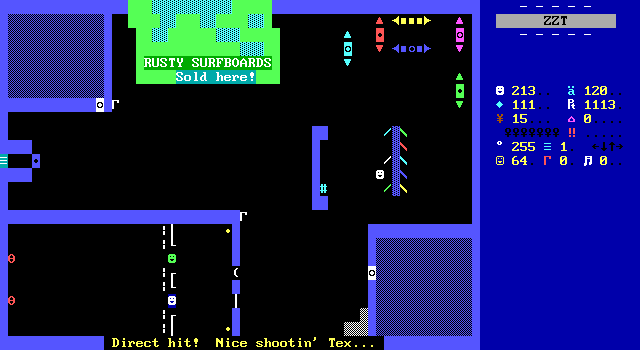

The combination surf-shop and shooting range may raise an eyebrow as well, but it's such a wild combo that I can't help but love the concept, though I don't think players were supposed to feel that way. There's a plethora of options at the counter to purchase surfboards, get one waxed, or buy shotguns and rifle scopes. Players can also visit the shooting range to practice their aim.

With no water to impede players, activating the range also lets them wander around it, taking their shots up close, or standing in front of the other target currently in use. The other patron Dave has no qualms with shooting around you, though he doesn't do a very good job of it. Of course, in the great trend of being able to kill random NPCs, drawing your gun on a man already firing ends up being a game over for the player. Don't shoot strangers.

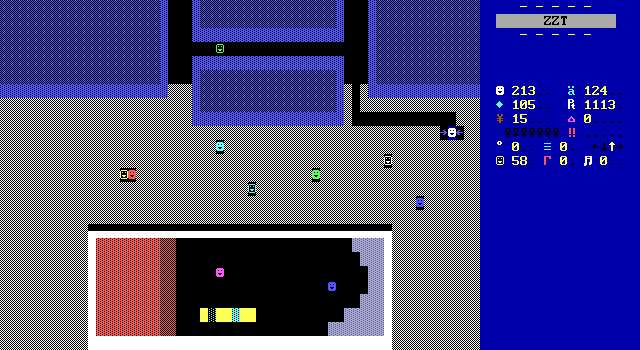

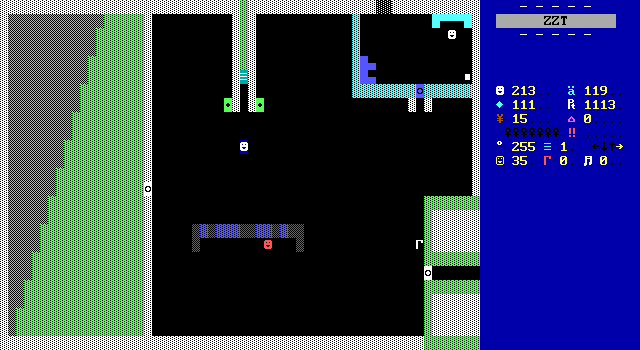

Depending on which way players navigate the streets of Miami, players will sooner or later find their way to the governor's office where they can ask the governor to open the portal chamber so that you can return home. The governor rightfully considers you to be another weirdo that wants to try and use the magic time-travel device whose origin goes curiously unexplained.

Talk to him about his secretary, and he'll agree that she's pretty, but "she knows all of his tricks". It's kind of gross!

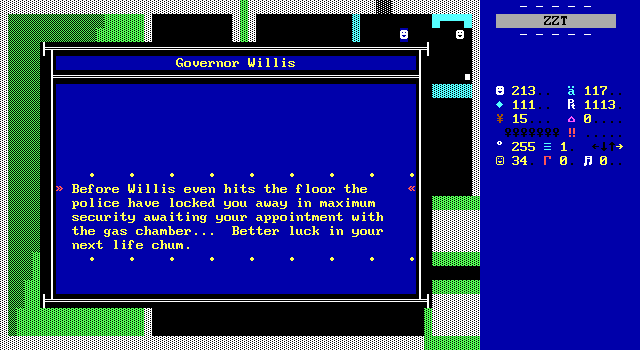

You can threaten the governor with violence, but he's not afraid as if you so much as try the place will immediately be swarmed with cops and you'll have no hope of escape.

If you call his bluff, you'll quickly learn he wasn't kidding. Contrast this with what happens if you shoot his secretary, a move I only dared try as she keeps yelling at players to stay away from the vault door that I knew I needed to get past. There are definitely some issues here. (Oh, and for the record, Florida has never had a governor Willis.)

Again, you don't have to do this. It's just an odd staple of early ZZT worlds. When you can program every object to react to being shot, some folks just want to make something happen.

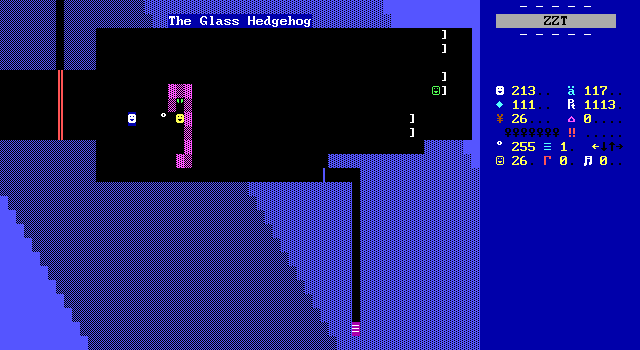

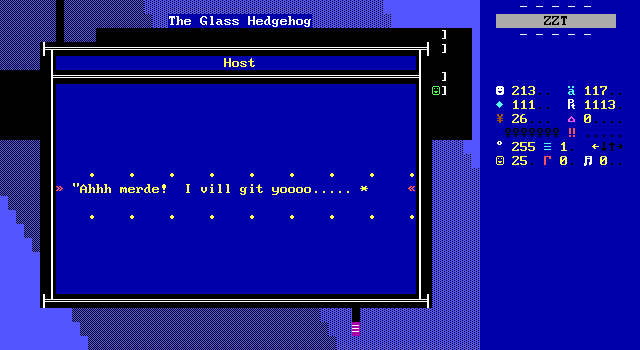

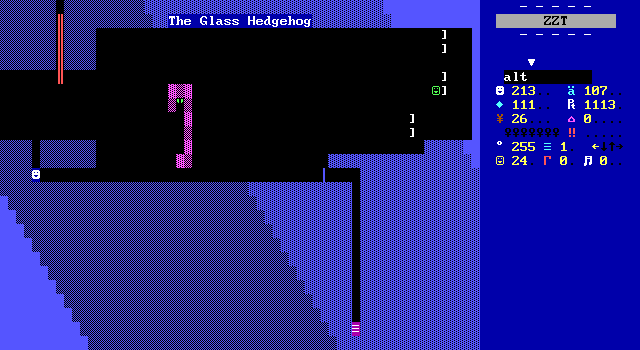

The same can't be said later on in the beautifully named "Glass Hedgehog" restaurant. A strict dress code means that the player is turned away in the lobby. In this case, the intended way of getting inside is to shoot the employee to gain access the panel that opens the door. Little thought is given into what that will mean for the future for this person to suddenly be killed. Surprising for a game whose author seems to be pumped for the new Terminator sequel.

Technically, you can avoid the killing, though the method of doing so is, ironically enough, shooting away the breakable walls that are used for shading in order to just tunnel around it. I just had my big screed about this!! (Notably, the seemingly-breakable walls surrounding the panel itself is properly made out of objects to prevent players from reaching it that way.)

And honestly, I'd really prefer that your gun wasn't the solution here. I've got no objections to violence in ZZT games, and the ability to kill everyone you meet in so many of these older ZZT titles makes me laugh more than anything else. (Aceland's Microwave is perhaps the pinnacle of ZZT violence for no reason, and I will never tire of using it.) Here though, even if the game doesn't take itself too seriously once you're in Miami, it just doesn't mesh well with the overall story of saving a humanity that destroyed itself through war. A distraction or a bribe would be welcome alternatives to completing your quest to save your species without having kill a member of said species in the process.

John Hoelle's Meaning of Life

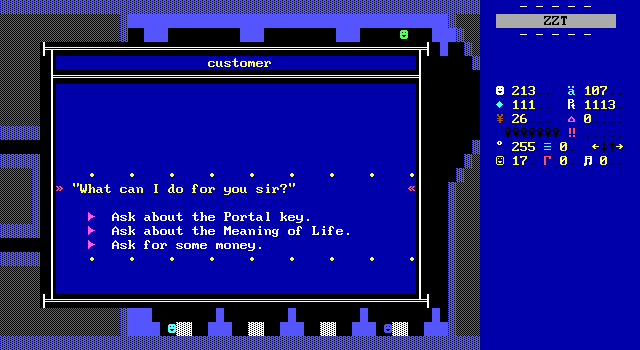

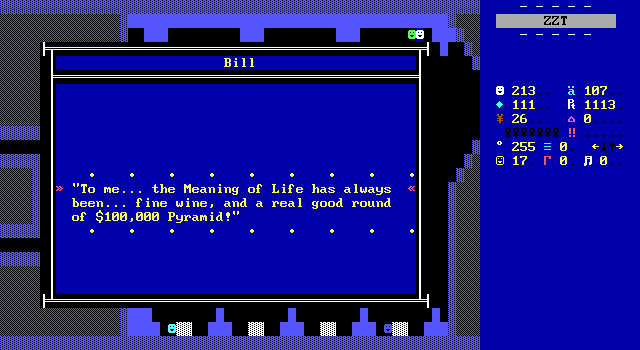

As much fun as it may be running around bothering people and being bothered by people, there is still a mission to accomplish. Finding the meaning of life, and then securing a way back home through the portal. These goals are worked on in tandem, with the time-traveler happy to walk up to any polite looking stranger and ask them what they know about either. Most efforts at the former goal yield little help, only some answers that you'd expect to see if the question was asked for a Family Feud survey.

While the answers aren't that varied, Hoelle has done his best to give NPCs personality via their answers. The metal-head at the record store will yell in your face about rock and roll. The young men working as waiters at the Glass Hedgehog will generally tell you its money, girls, or some ratio of money and girls.

Meanwhile one of the gentlemen able to afford a reservation to dine there has this very precise response:

And of course, the governor believes it to all be about power.

Your character never responds to these answers, likely disregarding them outright as "get women" isn't a philosophy that can help the human race turn around. The trail remains cold for much of the game, with the only real hint at what you're after coming from the blind time traveler in the park that suggests you find the futurist-philosopher Robert Anderson.

Mr. Anderson lives in an apartment in the east side of Miami, but a key is required to get inside. This in turn leads to the player finding hidden back alleys and speaking to The King of the Road who can help you procure such an item. Or you can choose to kick him to death from a menu of options on how to respond? The violence in this game is really something else.

That key gets you inside, but according to the landlord, Anderson fled after trashing his apartment and his whereabouts are currently unknown. A little white lie to the landlord gets you the key to his former room, where a letter addressed to his girlfriend reveals his current whereabouts in the local hotel with a copy of the room key. The protagonist is no narc though, so the landlord will never find him. Solidarity forever.

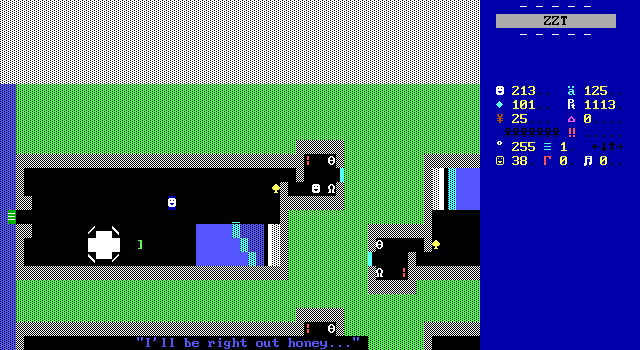

Meeting Anderson is nicely done. It's a dynamic scene when you arrive, with Anderson not merely sitting on a chair staring off into space. Instead, upon hearing the player's footsteps, he assumes it to be his girlfriend, calling out to her from the bathroom before he finishes washing his hands and steps outside only to be quite confused by your presence.

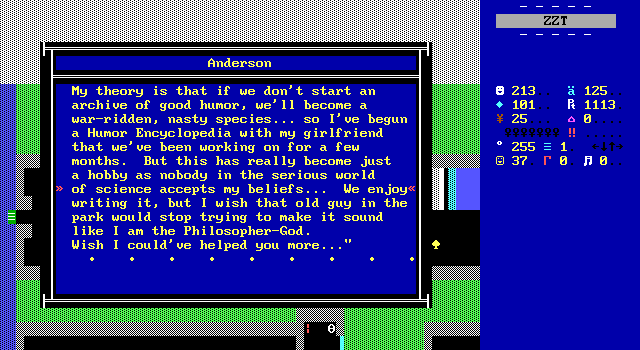

Robert, more than anybody else in human history apparently, really has things figured out. His theory is that what makes humanity thrive is humor. Without humor, the world would be a very bitter place. To that end him and his girlfriend have been working together on a Humor Encyclopedia full of jokes in hopes of sparing humanity from the dark future the player knows it to have.

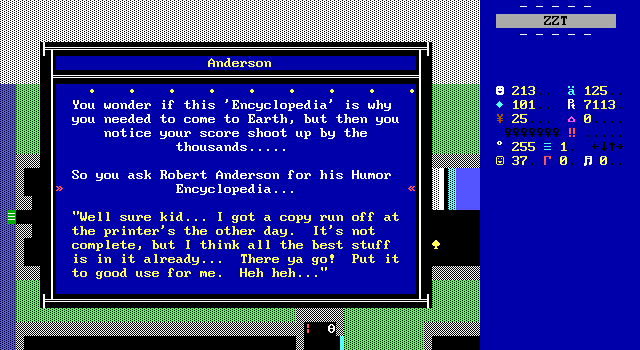

Remember that awful riddle about the nun with a spear in her head? The time traveler sure does, and it leads him to believe that Anderson may be on to something here. A copy of the almost complete manuscript is given away, and the mission is accomplished, leaving the player to just figure out how to get back home.

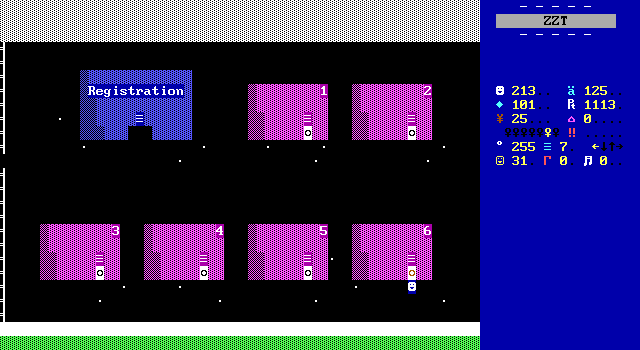

Getting home is difficult on its own. You arrived at the portal and just need to be able to open it once more to propel you back to the future. This means obtaining some keys which in turn mean obtaining vault combinations and such and such. All of this information is gathered from folks around town. The governor who hold some control over the portal will not help you.

Going through the game talking to everyone is enough to get all the information required save for the combination to the final lock which requires a key given to the player when they talk to Anderson about the portal. This is a quick way to ensure that players can't leave without the book (remember, no flags are ever set), that still allows for a breezy exit as players will most likely get the book, and then be activating the portal home only a few minutes later.

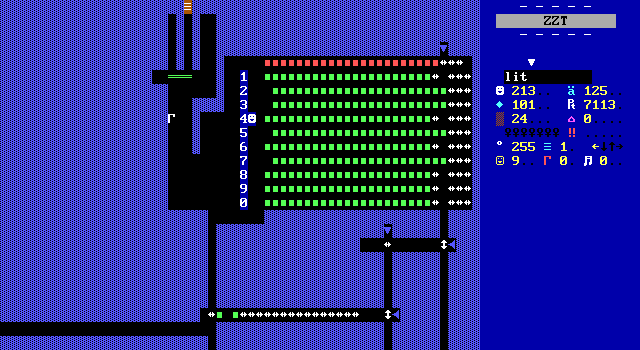

The combination lock is interesting in its own right. While it's clearly inspired by the one in Town's bank, this one is streamlined to have a dedicated switch for each possible digit. The end result is still a pusher being able to start moving, but the design means there's no order to the combination. 2357 is just as valid as 5372. This is pointed out to players explicitly, so Hoelle was obviously aware of the quirks of what he implemented here.

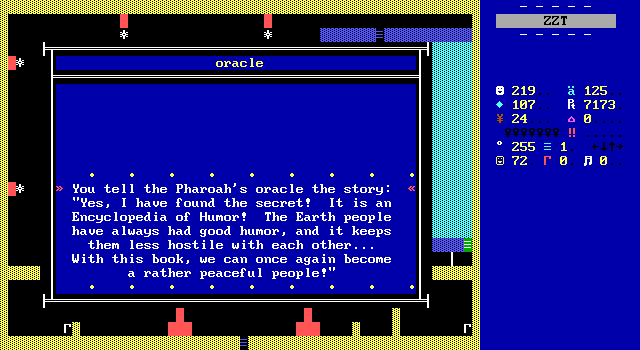

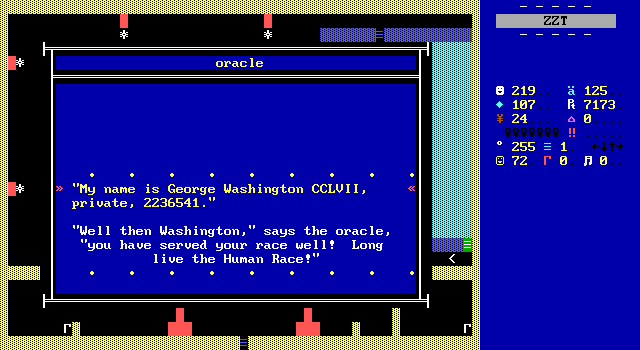

The trip home spares players the need to pick the right planet, conveniently returning them to the oracle's chamber from the start of the game where the player can present the oracle with the book. Everyone seems quite satisfied, though the ending doesn't tie a bow on it, with the oracle opting to say that if the book can save the human race, only then will the player's name go down in history. For one final closing surprise, only now is the player's name revealed.

Thank you Mr. George Washington.

Final Thoughts

This one was pretty cool! You could argue the game was a bait and switch with how dramatically different the game is on Northside compared to Earth, but for me that's really part of the game's appeal. It dabbled in multiple styles of gameplay in a very early era. It managed to do so much more naturally than later worlds like Ultima RPG did and it did so without literally splitting the game into multiple adventures as seen in NextGame 33 or Psyche.

The early more action-focused Northside section built up a good atmosphere, gave its world detail by giving locations specific names, and got me invested in where the player's journey might take them. The almost fake-out when it's revealed that your visit to Earth takes place in 1992 came as quite the surprise, but the new style's focus on exploration was more engaging and impressive than the still solid initial half. Spending so much time on Northside was a rather courageous choice when the game could just as easily have started outside of the time portal and being up front about where/when you were headed. Hoelle pulls off the bait-and-switch in a way where the opening chapter doesn't feel meaningless, and has enough substance and creative locations that it very well could be the setting of a complete game.

Chris Jong's 1992 release The Big Leap would do something similar as well with players exploring the present day for a bit before their own trip through time, but the time spent in 1992 there is more of a brief introduction, and players are well aware they won't be there for too long.

Upon arriving in Miami, things really begin and I found myself having a lot of fun poking and prodding at magazine racks, coolers, gas station pumps, and anything else I came across to see if it might be relevant or offer up some amusing insight from the man of 31,289. For players that are into these open environments to explore at their leisure, you can't go wrong with The Search for the Ancient, once you get there at least.

It's a fun world to visit for sure, and one I'd easily recommend to anyone looking for an early ZZT world that manages to avoid the common issues of obtuse design or limited resources. Granted, things are made a little more difficult by the Northside section where death is possible and players that don't pay attention to the text may find themselves struggling to find the necessary items to activate the portal, but I feel like all of it adds to the game more than it may potentially detract for those purely interested in life in the early 1990s.

Its one real detriment is that some of the text does feel a little dated now. The governor's relationship with his secretary feels skeevy, and with the protagonist offering no rebuttal to his comments, even to himself, it's hard to say if Hoelle intended the player to dislike the man or if his behavior was meant to be seen as the expected norm. The lack of commentary on what's presented makes it hard to read Hoelle's politics here, which could simply be a genuine belief in 90s conservative attitudes towards "health nuts", "rap music" (with them in turn putting "music" in quotes to suggest otherwise), and "ugh romance films", or just an uncritical reflection of common sentiments at the time being parroted back.

When you stop to dwell on it, things do feel a bit off, but actually playing the game myself, these moments were spaced out enough and most of the takes so utterly banal today that it's easy to cast them aside and focus on what Hoelle presents here that's more fun to explore. Seeing his chaotic restaurant kitchen, the enthusiastic rock fans of the record store, and running all across Miami slowly uncovering its secrets make for a great time that will quickly let you move forward.

Between the colorful characters, the unconventional businesses to be depicted in a ZZT game, and the care put into making sure players get to soak in the environment, it's hard not to have fun in what I feel ended up as a surprising success of early ZZT. Give this one a chance yourself, and perhaps you too can learn something of the ways of 1992.