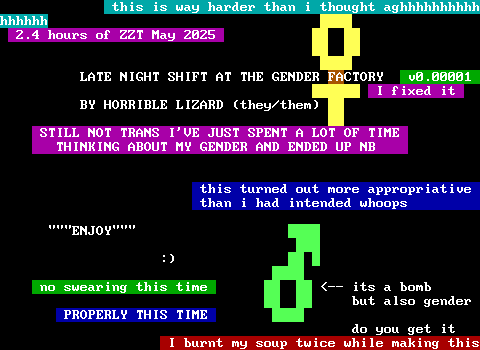

Sometimes you go through some stress in life. Things keep going wrong, the future is uncertain, and it seems impossible to do anything you want to be doing. When that happens, ZZT has your back. There are so many worlds out there that have such a positive and silly tone that it's impossible to not enjoy yourself for a little bit. So when I was recently down and needed to stop falling so far behind on my writing, I sought out to find one of these cheery little adventures.

You can't always judge a ZZT world by its title screen, or by flipping through a few boards, but there are a few tell tale signs of such worlds. ZZT's original restricted palette means that worlds are always bright, and frequently quite colorful as well. With the STK era came the era of realism, with drab grays and browns replacing the whimsical colors that came before. As many an angsty teenaged-ZZTer has lamented, it's hard to have your work taken seriously when every character is smiling all the time. Not that folks didn't try before methods to produce darker colors were established, but more often than not pre-STK worlds will at the very least not be a bummer.

Another good trick is to look at what kind of enemies the player has to deal with. The more an author uses ZZT's built-in creatures, the more likely they're not worried about looking mature. By the end of the 90s, using what ZZT provided was seen as amateurish. Object made a game yours. Tigers were tigers, no matter what game they were in. Hindsight has shown us that this view was really unwarranted, and that objects that loosely emulated the behavior of built-ins often caused more problems than they solved. Tigers may be tigers, but tigers don't kill other tigers with their shots the way objects do.

Ideally, you'd get some themeing to show that authors were more concerned with enemy behavior than what the editor said things were. This is all it really takes to make the enemies of a game your own. Alien Extinction, a previously unpreserved world streamed in 2022 has a simple opening scroll that immediately fires up the imagination for what bizarre creatures you're about to face off against. Sorry, that's not a lion, that's a scorpion alien. That tiger? Actually a gorilla alien. It invites players to think of worlds as places first, and games second.

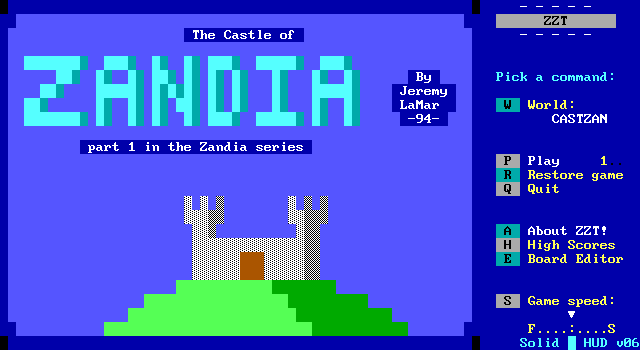

Castle of Zandia looked the part, and after having played through it, this one nails it. It's just what I wanted. A game of nothing but applause for the player and their actions, with vivid looking boards, comical characters, and some excellent design to match. There were no horrors of charm without compassion as seen in The Silly World of Dan Shootwrong. There were no repetitive boards with little to do as in Legend of Brandonia. This one was just fun from beginning to end. Exactly what I had hoped for, and best of all, it was a game by Jeremy LaMar, the legendary ZZTer behind Ned the Knight and MegaZeux's Bernard the Bard.

Getting to look at a prominent ZZTer's earlier titles is always a treat. If they're good, then it makes sense that they went on to greatness. If they're bad, then it's a great story about how they stuck around and went on to greatness. Either way, you can't lose. And while Zandia lacks in the complexity of Ned, the seeds are there. A bit of medieval fantasy with a lot of charm. Even without the link to Ned, this one had me matching the player, smiling from beginning to end.

Why Are We Even Here?

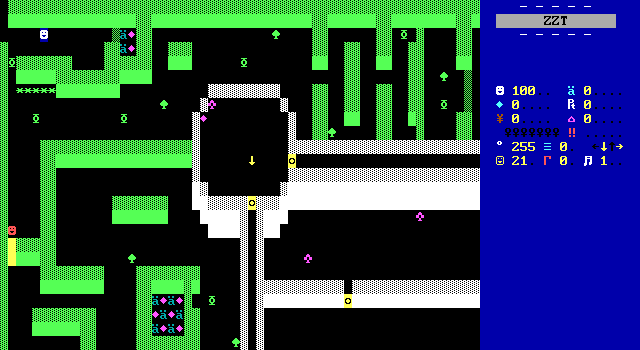

Probably the most unusual aspect of Castle of Zandia is how little story there is to the world. The protagonist is nameless. The setting is under-developed. Most of the friendly faces you see are simply described as allies, and the enemies are mostly ZZT's built-ins with the limited number of object-based enemies rarely having anything to say beyond "You shouldn't be here" and "Argh!" when shot. Early ZZT worlds definitely focused much more on boards as individual challenges to be conquered more than to create worlds that aid in telling a story. Even so, this one is impressively devoid of text. Many of the games included in ZZT's Revenge offered some motivation for players ranging from stopping "great evils" to obtaining the deed to a manor, to stopping a mad scientist from polluting the world into submission.

Even going all the way back to the Sweeney created worlds of the original ZZT saga more story can be found there than much of Zandia. City and Dungeons are about escape. Town and Caves are about gaining access to mysterious palaces. Zandia is about hanging around in a courtyard and entering a castle not because it is a place of wonder, but just because it happens to be near where the player starts.

This isn't an inherent detriment to the experience. Those original ZZT worlds tend to give the player their motivation on the first board and make no real mention of it until the goal has been reached. The worlds of Revenge only do slightly better. All of these worlds are here for players to explore numerous boards and survive the gauntlet, perhaps setting a high score at the end of it all. You won't find yourself thinking about how these worlds would seriously function. You just get up and go.

But Zandia offers none of it. Players get up and go for a third of the game before the king is brought up at all, and even then all players learn is that the castle is his and he's running away from them. Another third goes by before there's an update that the king must be on the surface after traveling through a series of underground tunnels. Finally players find a note from the king where he confidently states that there's no way the player will survive the jungle and its temple.

It's a safe bet from the first mention of a fleeing king that he's some level of tyrant, but there's nothing at all for so long that it takes until players find the note and see that it's signed "The Evil King" that the question of what Zandia is about can be answered. In Town, players discover immediately that the game is about finding the five purple keys to unlock the palace, even if why the player is doing so never gets answered.

Revenge-Like

To some extent when I say a game feels like something out of ZZT's revenge, I speak of the complexity of the game. There's a pretty clear leap over the mostly barren worlds created by Sweeney and the second generation of ZZT worlds submitted as contest entries for the Revenge and Best of compilations. Players can expect numerous NPCs throughout their journeys to offer advice, provide directions, and make the sure player is keeping up with what's going on around them.

At the same time, these worlds feel very simple and Town-adjacent. If you move on to the hits of the STK-era, you'll have a harder time finding games where the opening text is all the information you really need. The introduction to Escape From Castle ZaZoomDa tells players they're fighting against a rival kingdom. By the end of the game, players wind up in outer space saving the world from aliens (who were disguised as ZaZoomDians). End Of the World begins with a comet on a collision-course with Earth. By the end of the game, players wind up in outer space saving the world from aliens (who sent the comet to Earth). Sivion begins with exploring and helping the residents in the small town of Bespin. By the end of the game, players don't actually fight any aliens, but they do deal with a demon's attempts to return to power over humanity. You get the idea.

With Zandia's utter lack of story development, and arguably storytelling at all, the game feels a bit more like the titles that came before it rather than relating to contemporary releases.

The cool thing about ZZT though, is that there is no correct way to design a game for the engine. All levels of complexity have been host to some wonderful games, whether that's Town, Ezanya, Code Red, For Elise, etc. etc. This one is more of a brisk Link's Adventure that takes players on a set path through various environments connected with its share of puzzles to solve and enemies to fight.

The very start of the game puts players in a location that shows care was put into its design. Your quest begins outside the castle, searching for the key to the secret passage that will get you inside. It's a promising start that makes great use of the scale of ZZT's boards, properly dividing things up into a few regions, with some not immediately accessible so as to get players wanting to go to these places they can see, but not yet reach.

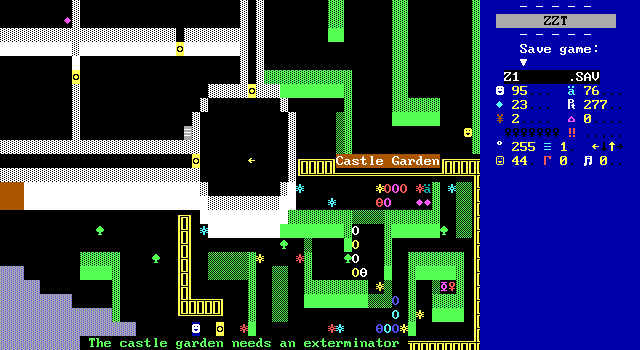

For early ZZT grassland, the heavy use of green is to be expected. LaMar keeps his colors sensible sure, but he knows how to effectively add splashes of color that make some sections of the outer-walls really pop.

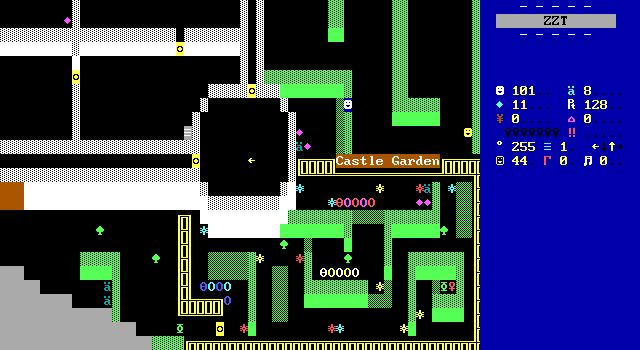

This garden showed up only a few minutes into the game, where it instantly won me over. The first few boards of any ZZT game I go into knowing nothing about are always have me feeling anxious, as I have to wonder if this game is going to be the one I want to spend my time on later. As soon as I saw this garden, I knew Zandia was a good call.

Some line walls, the color variety in the garden's flowers, and then using the centipedes to incorporate the remaining colors of ZZT's baseline seven color palette create a region that you simply have to find a way into.

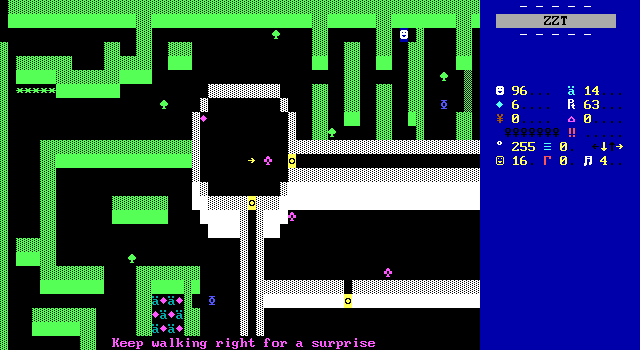

These little observations make it even better when you actually find your way around. LaMar goes heavy on these scrolls through much of Zandia, putting the author's voice directly into the game with little remarks about what the player will be dealing with next. There's something charming about the blunt way the author speaks directly to the player like this through scrolls instead of having the same comment from an NPC diagetically. ZZT games, whose companies were only pretend rather than employers, aren't afraid to make it known that they were made by people.

It's a sentiment seen repeatedly. While the first scroll says that these messages will contain useful hints, it's hard not to see the enthusiasm of a ZZTer proud of what they've put together. Fake walls are particularly popular, with the first few having scrolls to make sure players know how they work. Other scrolls will teach players the basics of ZZT, in case this is their first adventure. I suspect if LaMar had any local playtesters, there's a good chance it was.

The cheerfulness seen in Zandia goes a long way in making players comfortable. Successfully get an enemy to shoot themselves with the help of a ricochet and your prize is accompanied by a message of celebration.

It's not entirely pats on the back for a job well done. Zandia is a dangerous place. Thieves, ruffians, and guards make up most of the enemies. Shooting is a critical skill to survive the castle's occupants, with most levels guarded by a boss creature that steals the show.

Other worlds have admittedly done it better. The one time Lamar leans in on designing a world is to make the ruffians low-level guards, generally avoiding ZZT's more bestial adversaries unless he can find a way to explain their presence. Each of ZZT's creatures has their ideal environments to pose a threat, but rarely can they do it all by themselves. This could be taken as a negative, but I didn't really see it as such at the time. Instead, the action of Zandia felt "light", contributing the breezy feeling of the game as you rarely need to hold your ground for long.

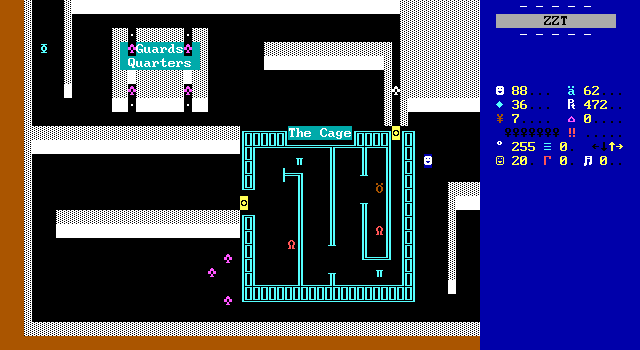

It also makes boards feel more special when LaMar finds a way to incorporate other enemies. "The Cage" is trivial, a smattering of creatures spread out in such a way that you'll probably never be worried about more than one enemy at once. While it lacks in excitement, it instead provides more memorable scenery. Without these rules for when lions, and tigers, and bears[1] can show up, I suspect this board would have been no more than a right angle instead.

The sensible explanation for enemies shows up a second time on this same board with duplicators representing guards rushing out to deal with an intruding player versus them being a device to create clones. Considering the logic of why the enemies are where they are and what they are really isn't something you see all that often, especially in earlier worlds like this.

Though the enemy placement rules often prevent inter-mingling, the structure of Zandia gives most creatures a moment to be the primary antagonists. Much like how Coolness begins with finding something to do on a boring afternoon only for players to wind up in outer space saving the world from aliens, the castle of Zandia, is merely the beginning.

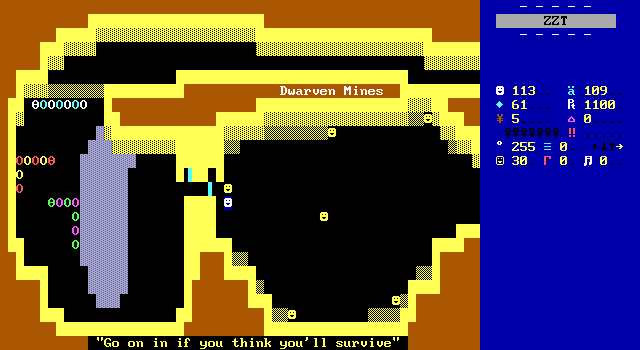

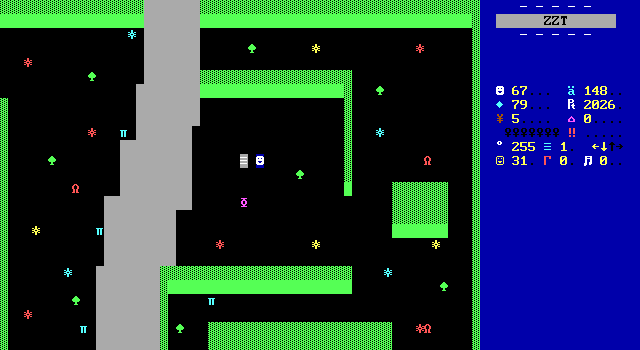

An underground passage awaits players after they're finished the game's first chapter. Here in the mines, centipedes are the enemy of choice.

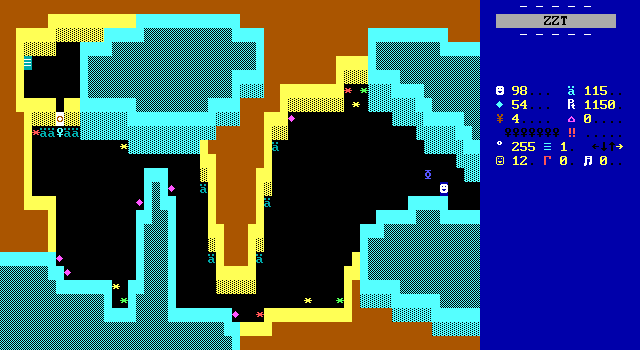

Slimes also find their chance to shine, tasking players with stopping the spread before it gets out of hand, and leaving them to blast away any residue to reach the other side of the cave.

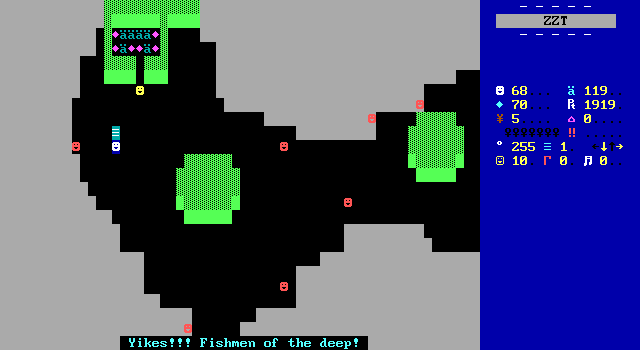

After the underground, players ascend to the surface along a lake where a new fishman becomes the next challenger. These guys are identical to the gem thieves in both appearance and behavior, though they do move a little faster (and also don't take gems).

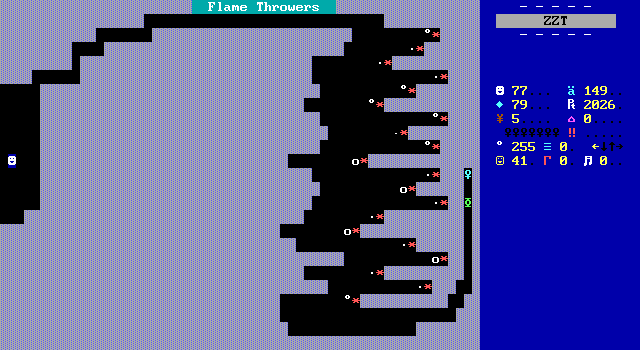

I've got nothing for how this board could possibly fit it with the rest of the game. Watch out for fireballs I guess. Still, another board with exclusive one enemy, this time, more of an obstacle really as players can't kill the fire. Instead they need to dodge past the flame objects that head directly west, singing anyone in their way.

Things return to normalcy pretty quickly, as the lake segment is over almost as quickly as it starts.

The jungle hearkens back to the game's beginning, this time without the thieves and with lions and tigers. Once again the right creatures are picked for the job. The tigers can shoot bullets over the river forcing players to either spend ammo shooting back from a distance hoping to hit their target without using too much ammo, or to try their best to ignore the shots and focus on getting to the next board instead.

Ultimately, the action of Zandia is good enough, which is good enough for me. LaMar's decision to rationalize which enemies can appear on a given board is an idea that was worth exploring. The results are pretty clear though. It makes the game's combat underwhelming (save for some boss fights to be discussed later). Thanks to the fun designs of its levels, the whimsical allies on your quest, and some impressive work with puzzles, the game doesn't really suffer all that much. Depending on your tastes, the short bursts of action can just as easily be a positive. Myself, I'd appreciate not having to park in one place and shoot at all the ruffians until it's safe to move forward.

It bears reiterating as well that this is LaMar's first ZZT release. "Good enough" is something to be proud of here.

A Little Help From My Friends

The nameless protagonist of Zandia isn't the only character to be found. While LaMar incorporates himself into the game with some scrolls, there exist a large number of friendly NPCs that also want to help players out.

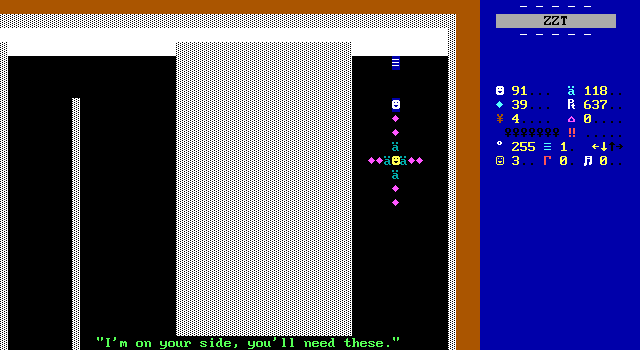

They don't do much, but you can count on them to show up when they're needed. Boss battles always give way to a new friend who will provide some one time boost to health or ammo, often commenting on the tough fight players just finished. Most just sit in place, provide the supplies, and then offer a single line of text when touched again.

Some get to have some fun with their hand-outs, spilling goodies on the board for the player to pick up while others move out of the way of already visible items.

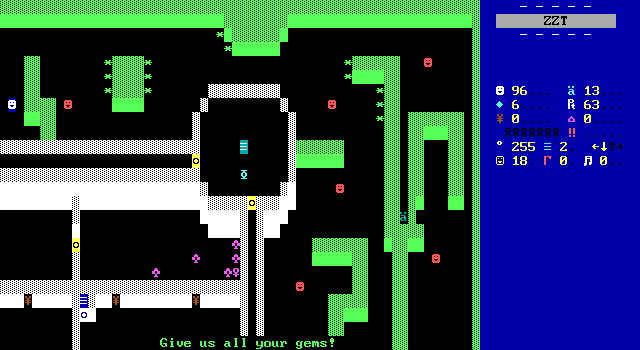

Some of them aren't running charities.

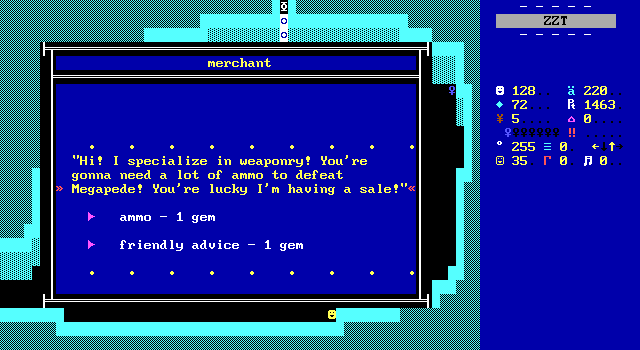

In addition to plenty of small boosts to supplies provided by people rather than something more common like a treasure chest, Zandia also has two shopkeepers. The first is found outside the castle and the other about halfway through the game selling ammo just before a boss fight. The prices are low. The gems are plentiful. Together, you wind up actually doing a decent amount of shopping in a ZZT game for a change.

In fact, early on it's worth spending a lot of cash on torches which are surprisingly hard to come across given the number of dark rooms to be navigated. These sequences happen early enough that it's not too annoying to have to run back to buy more, though it's obviously more preferable to save yourself the trip.

Both shopkeepers are more interested in getting gems than in helping out. Each one also sells advice, which tends to be an annoying things to spend money on in ZZT worlds when you can just load your save afterwards. LaMar gets around this by pricing the advice at a single gem, and by making the advice a complete waste of your time, with the messages delivered having no relevance to the game. The information you receive more akin to "Don't run with scissors" than "There's a secret passage behind the suit of armor".

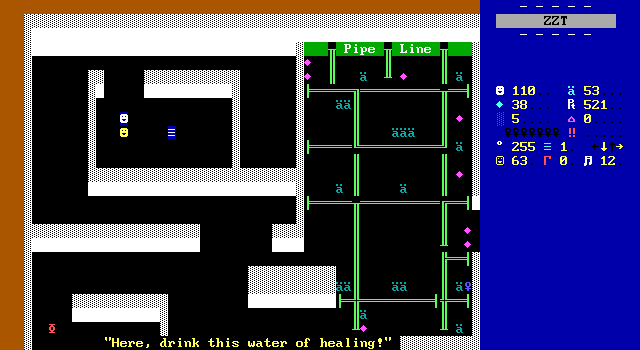

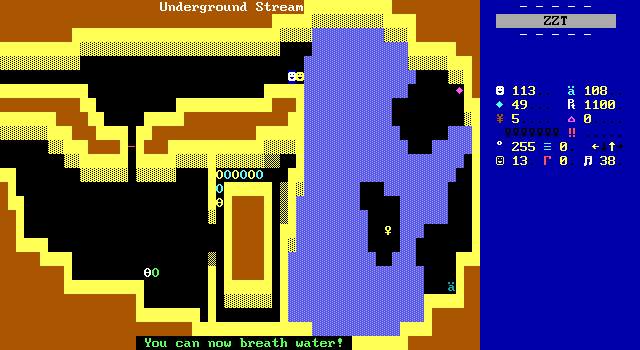

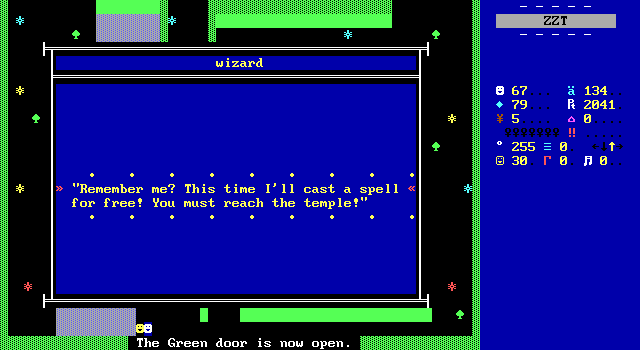

One NPC actually appears more than once. A wizard found hanging out in the underground offers their services for a small fee.

A little water-breathing spell later, and the player gains the ability to swim, handled by #change replacing the water with fakes.

In what I suppose could be considered character growth, the wizard shows up once more in the jungle on the path to the temple where the final boss awaits. Maybe they felt guilty about taking money the first time, or maybe now they have faith that the player is the one who will save the people of Zandia. Whatever the motivation, the second encounter requires no payment. Just an act of goodwill to vanish the water and allow players access to the other side of the jungle.

What stands out to me with all these little NPCs cheering the player on is how they appear throughout the adventure and not just in a starting town. These people are being brave themselves! Whether it's the castle, underground, mines, lake, and jungle, no matter what dangers the player may face, they'll constantly be running into those who want to help however they can.

It has a strong impact on the game's tone. Since so much of what they do is provide supplies, your typical ZZT adventure would be all too happy to replace them with treasure chests, or worse, just piles of items to grab. These people instead commend your successes, and warn you of the dangers up ahead. You may be playing the role of the hero here, but it's not up to you and you alone to take down the king. Those yellow smiley faces are your comrades.

- [1] I'm allowed to make this joke since LaMar also does.

- [2] Take a look at "The Key Dispenser" from The Lost Pyramid for a puzzle accidentally made trivial. What should be an intricate lock to unravel falls apart once you realize the player has room to get inside the structure and start pushing things themselves. As for the extremely difficult, Machinations from Best of ZZT Part I was unknown to have been solved by anyone until just a few years ago.