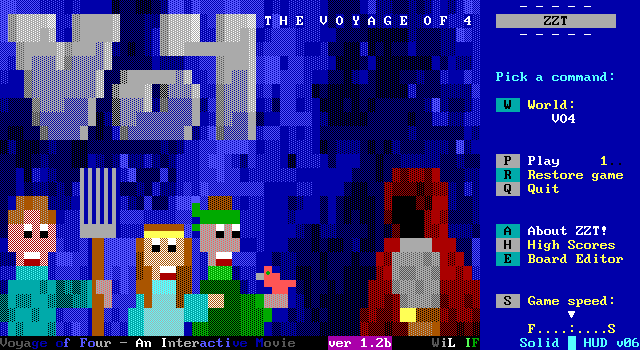

The poll winner for April (oops) was none other than WiL's Voyage of Four. It's a challenging ZZT world to cover, and not just because WiL is still hanging around and creating new Weave ZZT games. This is a difficult one because above all else, it is a story, and I don't want to merely write a book report for middle school English.

Voyage of Four is yet another WiL game which I was around for the release of, and managed to have it completely pass me by. Maybe I played it and quit after a bunch of cutscenes because I was still twelve years old and not known for my taste in the fine art. "Wow this 'Banana Quest' is really neat. Time to not finish it and never look at anything else the creator makes for 20 years" - probably my exact words as a child.

Of course the Closer Look project has been nothing but me constantly lamenting not playing these games back when I had the chance. Heck, this one is even published under Interactive Fantasies! There's no way I should've missed this one. Well, my takes on games are a tad more refined these days at least, so perhaps it's for the best that I played it now when I can really appreciate what it does, and the fact that it does what it does all the way back in 2001.

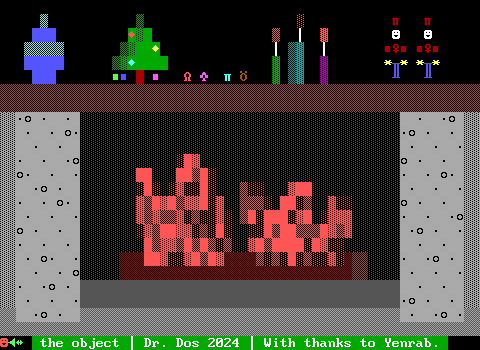

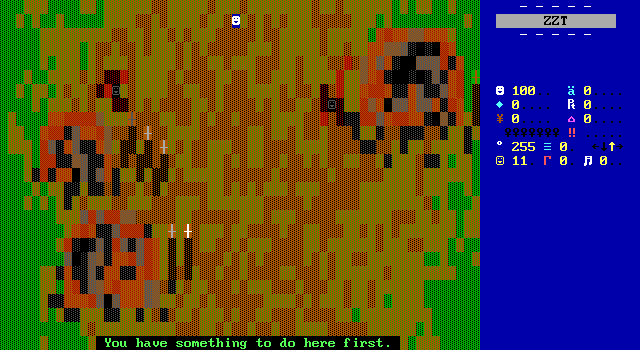

The text file WiL includes with Voyage of Four describes itself as an "Interactive Movie/RPG" as well as his "first serious ZZT work". Lots of loaded phrases there that instantly paint images in any experienced ZZTer's mind as to what to expect. Characters that have feelings. Battles that desperately wish they were Final Fantasy. We've seen it plenty of times. It's a very tough sell to make today for a game of this vintage.

But this is WiL we're talking about. Later in 2001 the Interactive Fantasies group project Death Gate would release, with one of the game's chapters created by WiL who steals the show in a world that struggles to be more than mediocre. WiL, who would maintain a still-ongoing reputation as one of ZZT's strongest composers is equally deserving of praise for his impressive storytelling abilities. The bar may have been low at the time, but Voyage of Four is one of the few "serious" titles of the era that not only stood proud then, but continues to do so to this very day.

This is definitely a good time to pause for a moment and mention that a second author, Avatar, is credited for their work on the story, so WiL shouldn't get all the credit here.

Many of these more serious ZZT games fall flat. Stories tend to feel made up as they go along, or with abrupt shifts to shuffle characters from where they are to where they need to be. If two characters are to struggle to deal with one another only to become best friends, you can safely bet that a single event will effectively flip a switch rather than have the characters develop that relationship naturally over time. WiL has a bit of an ethos with this one, a shared motivation for all the protagonists that each one manifests in a different way. Narrator Cresh-Osk helpfully spells it out to players from the very beginning: "What they knew no longer is, what they want is within their grasp."

Interactive Cinema

What could be more fortunate than getting two worlds in a row that bill themselves as "Interactive Cinema"! In the case of Dark Soul, while label certainly applied, I feel like it wasn't really Fishfood's intention to make a game so reliant on telling its story through cinema. Dark Soul billed itself as a chapter one, where players needed to be introduced to the world, its norms, and its characters. I feel like had the game been continued, the later chapters would have an easier time combining storytelling with the gameplay, something that couldn't be done in the first chapter until things started going wrong.

Because of this, I didn't once see reason to compare to ZZT's most iconic and very much non-interactive cinema: kev-san's Freedom, a ZZT rock opera that set out to tell its story with a heavy lean on music. These days, Freedom is hardly seen as a masterpiece, with the world struggling to actually tell much of a story, while the music and dialog struggle to sync up. Instead it's seen more as an important step in acknowledging that ZZT doesn't have to be used to make traditional "games". A world could be devoid of player input entirely, and still be a satisfying experience. ZZT could be high art.

A few other worlds went in a similar direction, though few were willing to go as far as kev-san and focus solely on getting players to watch rather than play out scenes. Voyage of Four, despite offering its share of the more expected moments of gameplay in the form of RPG combat (always and forever RPG combat), is the first of these games, that I feel really figured it out.

The world may not actually be 100% cinema by volume, but its heart lies in telling players its story[1]. The focus is on how the characters deal with conflicts and grow from them. How they handle moments of despair. How they cling to hope. How they long to right wrongs and leave the world in a better state than they found. Most ZZTers that attempted serious stories asked players to heavily emphasize with characters because the narration told us they were sad. Even well regarded worlds such as the Rhygar trilogy were frequently guilty of characters falling in love because they were a boy and a girl that spent time together. Relationships, romantic or platonic, often feel forced, with characters that just met immediately having eternal unbreakable bonds with one another. These games feel less like authors coming up with compelling stories and more like them having a list of tropes seen in compelling stories that need to be included. With the bulk of these worlds coming from then-teenagers, it's no surprise that those still figuring out relationships (romantic or otherwise) themselves aren't exactly getting it perfect in their art either.

Unlike, virtually every other ZZT world out there, WiL has managed, more than twenty years ago, to create one of the most resonating stories in a ZZT game I've come across. The cast felt diverse in background, ability, and personality while still managing to have believable interactions with one another. The war waging in the background for the first of the game's two files is merely a good justification for these four to band together.

The storytelling is the cornerstone of the game that successfully carries players from the beginning to the end. Or at least to the end of the first file. Things get shakier in file two when that background war (really, it's anything but) is almost completely discarded for some bizarre last chapter revelations. The story goes places in the end that took some time to appreciate. Whereas when I was actually experiencing it firsthand, I had a sinking feeling that everything I knew no longer was, but what I wanted was no longer within my grasp.

Even so, the first file is a satisfying experience on its own, just one that lacks a conclusion that could be described as simple. Whether the end of the ride is worth it to you in the end, the journey voyage will surely leave a mark.

A significant portion of the first file is spent building up characters through their acts rather than through liner notes. Characters are introduced as one would introduce real people. Life stories are not immediately dropped in the player's lap, nor do players get little profiles explaining "Oh this guy is hot-headed and fiercely loyal!" Any insights on the characters have to be figured out for yourself, and when so much of what you do is sit and experience the events of the game, the fact that it's appealing to get to know the game's cast better should be enough to understand why this game is a unique specimen.

As with other interactive cinemas, plenty of the times when players aren't penned in the corner of the board waiting for a scene to finish just as well could have been additional cinematic scenes. Even when WiL offers players that little bit of freedom to explore, they're still locked onto a set path. Early on, a very clever technique is used where the border of a board is made out of normal walls matching the fake walls that make up the ground. WiL uses this to ensure that players still are seeing everything they need to see, essentially keeping them locked to the script as if these scenes still were cinemas. In this way, WiL was still able to assuage any fears ZZTers had that there was no game to be played while still maintaining complete control to tell the story he wanted.

Alternatively, this technique is really only seen in some of the earliest boards. Perhaps WiL himself was the one that needed reassuring here. It's quite possible to never have free control of the player element for the rest of the file with only a few alternate scenes letting players touch an object before walking into a passage on the board rather than running it all automatically and shoving the player into the corner.

Of Course There's an RPG Battle Engine

Why wouldn't there be?

The box is ticked once more, we're a few years from Y2K, and so the pinnacle of action in ZZT remains the RPG battle engine. Lions are so 1995. It's the twenty-first century.

WiL, being a skilled ZZT-OOP programmer even back then takes a try at the same thing everybody else has done a hundred times before him. Of course, WiL has never been content for his games to merely imitate, and there's plenty of spins on this engine that make it apparent that WiL wants to innovate in the overdone RPG engine department.

Unlike the recently covered Dark Soul, where plans for a second RPG battle could be found on an unused board, Voyage of Four is confident enough in its engine to use it repeatedly. The specific number of battles depends on what route players take through the game, with a total of eight spread throughout both files.

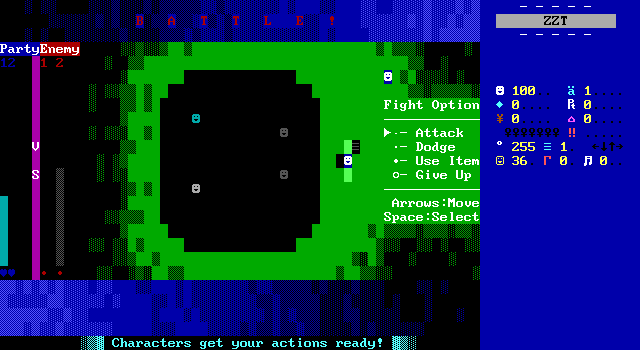

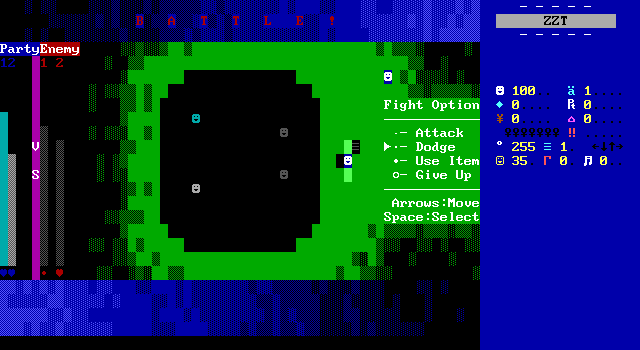

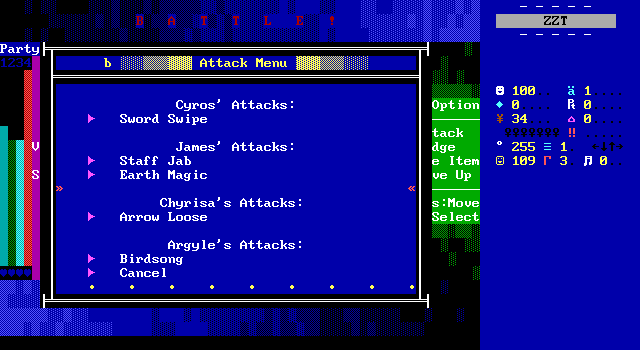

In it, players issue commands for up to four different characters each turn, fighting enemy parties with up to three targets. By ZZT standards this is a hefty number on both sides. At a time when a solid RPG engine was solid resume material

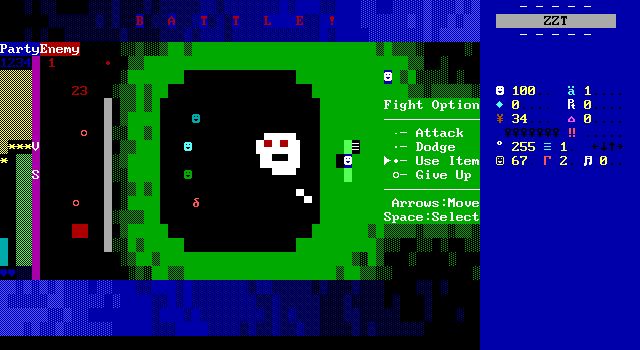

As with Fishfood's RPG engine seen before, the engine is still guilty of indulging in my pet peeve of having ZZT's message windows cover up health meters which makes it difficult to choose the ideal course of action. Given how crowded the board is to handle all those health meters encoded in breakable walls, I can forgive him. I think a horizontal health bar arrangement still would have worked, though it might get dicey with the boss fights that use ricochets to deflect bullets in order to give bosses health bars too long to fit in a single column. At the very least, even a full four character party will have it's health visible even with a message window open.

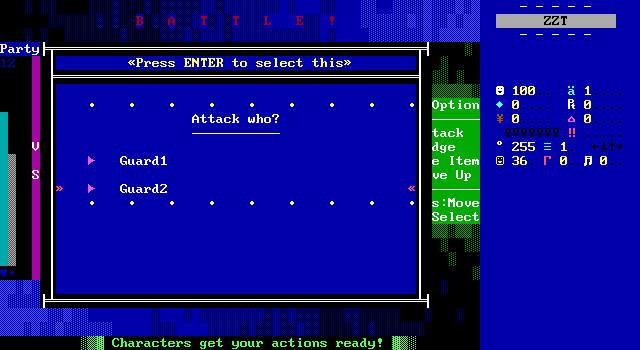

Although the specific actions still rely on the typical pop-up style of having players select hyperlinks from a menu, the more general actions use an on-screen interface. Upon entering the board, players are shoved into a single tile where objects to the north and south can be touched to navigate the options seen on the right side of the board. This covers attacking, dodging, using items, and a unique surrender option which all all accessed by pressing space to have a player clone shoot which another object will detect and bring up the appropriate menu.

What sets this engine apart from most others is the way that rather than input commands character by character, players first use these options to determine how a character should act, and then specify which character. The engine still runs in real time, so navigating the on-board menu quickly is critical, though once a pop-up is opened players can take time on the specifics. You need to get all your players ready quickly lest their turn be skipped.

There's a major advantage to this. Mistakes can be corrected. Picking the wrong target or realizing a character is gravely injured and should try to dodge instead of attack is no longer something you have to live with. Just issue a new command and the old one will be discarded.

A very enjoyable aspect of this is that when your party does execute their commands, they'll do so one after the other immediately making your attacks feel like they're being combined. Telling all four characters to unleash their most powerful attacks on the same target and watching as more than a dozen bullets are spit out to knock down the foe's health is really satisfying. The fights feel exciting as conditions can change wildly every round.

The guts of the system are very well hidden. Using SolidHUD I could watch my flag counter adjust constantly during the fight, though only a single flag is used which seems to be whether a coin would flip heads or tails on any given cycle. Whatever system is used to store selected commands is kept out of the player's sight. The engine feels very clean. Information player's don't need to know is kept well hidden. This means no sounds of bullets shooting random targets to roll damage and no waiting for timers to fill up that can't be influenced.

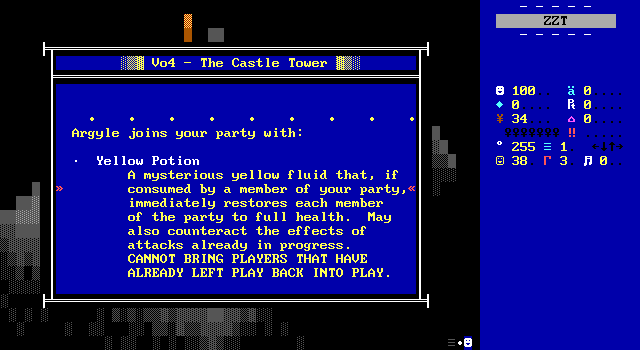

The item system is one that makes Voyage of Four's battle play out rather different than most. As this is a cinema focus game rather than a traditional ZZT RPG, there are no shops to visit or treasure chests in dungeons to loot. Instead, items are handed out as rewards after certain fights which makes what items players can have at any given moment set in stone. It's a practical way to add more depth to the combat without having to restructure the rest of the game to support it. There's just one snag. It takes a very long time until players start getting items, making the function useless in probably half or more of the game's fights. Perhaps a simple "start with two healing potions" or something might have added more strategic depth to these early fights which mostly amount to spamming attack instead.

When they do show up, the actual items are pretty clever. ZZTers have had to take some creative approaches to approximating 90s-era console RPGs, usually trying to shy away from the fact that a "health bar" is just breakable walls and damage being dealt is just shooting bullets at those walls. WiL's items take advantage of the fact that this is all ZZT elements at its core and exploits those properties to engineer some unconventional items that are far more powerful than your standard healing potion.

ZZT games that have breakables for health often don't bother with healing at all. Those that do try to patch in some new walls by having an object shove a few boulders into place and turn them into breakables. For anything other than a full heal, this means the health bar now has an unsightly gap in it. WiL instead says "this potion will heal your entire party to maximum health", and then places a slime in the health bar area. The slime floods all the empties with breakables and now your party is in tip-top shape. At least, as long as they were alive to begin with. If the object at the end of a health bar is shot, that's it for the character.

An alternative healing potion also has the ability to nullify any attacks being endured (albeit on both sides). This does the same thing with slime, changing any bullets to empties first. Items are used instantly rather than taking over a character's attack or dodge, so when a massive and lethal amount of damage is headed your way, quaffing the potion puts a stop to it. Just the same, when you do start fighting bosses with twisty health meters that rely on ricochets to fit, you'll have to wait until those bullets are finally cleared. The system is somewhat along the lines of Earthbound with its rolling health counters let players take action before it rolls to zero. It doesn't seem like it should play all that much differently, but in those moments where the quirks can let you shift things into your favor, they're a welcome sight.

Character Overview

The Four Voyagers

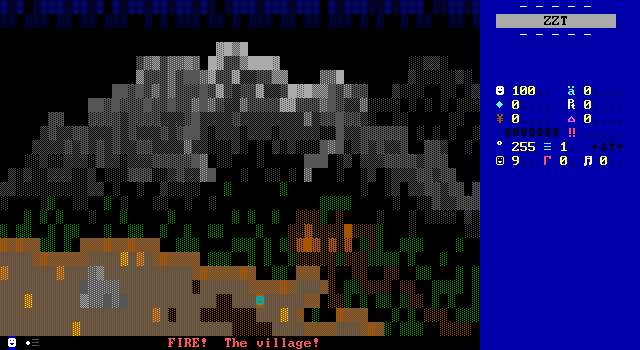

Cyros - The game's main protagonist. More often than not, if the player is in control rather than watching a cinema, they'll be controlling Cyros. A farmer with a talent for playing the recorder that loses his family and village after an attack by the Tara empire. Swearing revenge on the "man in red" responsible, he sets out to seek revenge and spare the other villages of the Outlands from the same fate as his hometown. Little does he know, that he is fated to accomplish so much more than vengeance.

James - A survivor of another attack by Tara's forces. James was imprisoned as a fraud after trying to convince an elder that their town would be next to be attacked. Together with Cyros, the two unite to travel from town to town preparing the villagers to fend off the invaders and turn the tide of war in the favor of the Outlanders.

Chyrisa - The princess of Rehana, bored of royal life with a longing to see the outside world. When she begins to suspect her brother is going to usurp the throne and dispose of her, she flees the kingdom to the Outlands. Only there does she discover that it's hardly a place for a princess. Undaunted, once she meets Cyros and James she vows to become a capable fighter, and one that can use her royal status to make her a symbol to rally behind in the fight against Tara

Argyle - A mysterious wizard with whom James is acquainted with. Argyle never speaks, communicating only through birdsong, letting James do any necessary translation. His magical abilities allow the group to face off against nearly any threat and surpass any obstacle.

This Asshole

The Man In Red - The unknown leader of the Tara army responsible for the empire's sudden embrace of imperialist power. Nothing is known about him, beyond Cyros knowing that it was him that killed his family and had his village burned. Our heroes have no idea who they are truly dealing with. Perhaps this villain has no idea what they are truly fighting for as well.

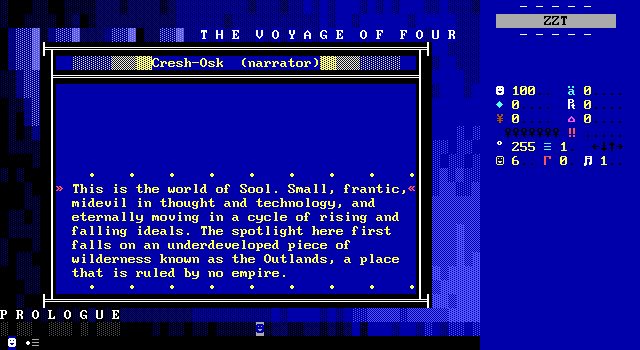

Voyage of Two

The story begins with the narrator "Cresh-Osk" introducing things. Cresh shows up between acts to move the focus from scene to scene as well as summarize what has happened in the world during the various time skips. The story told here is a long struggle that unfolds over the course of years.

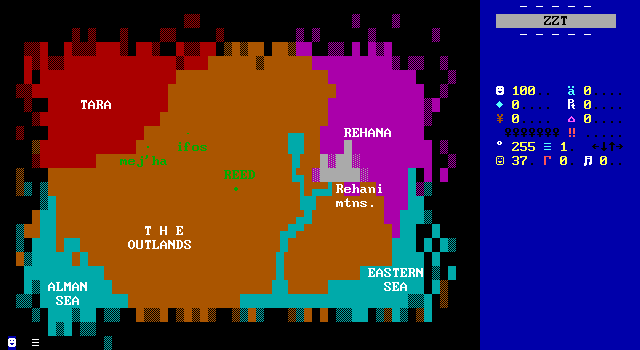

The story takes place in the world of Sool, a medieval-era land divided into three regions. Tara to the west, Rehana to the east, and the main focus "The Outlands" that make up the central area. Here in the Outlands many smaller rural towns allow people to generally live as they please, being able to keep to themselves in exchange for a hard life in what's considered to be mostly treacherous wilderness.

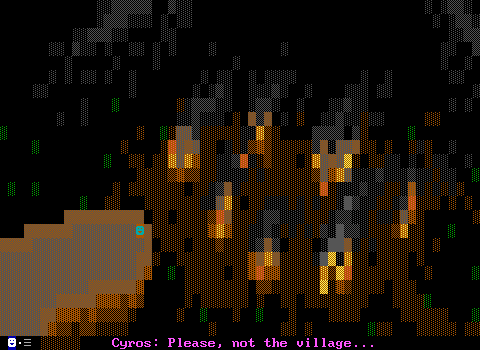

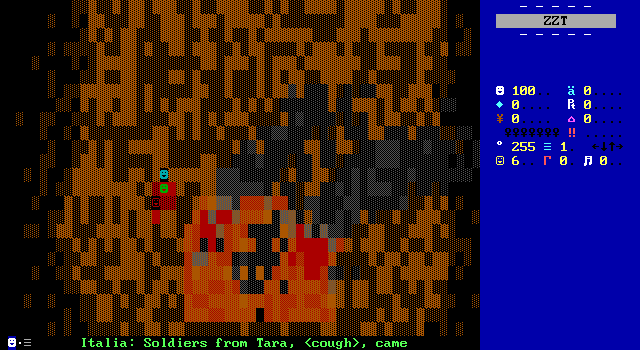

Cyros, a farmer is taking a hard earned break from work to spend some time in nature, ascending one of the nearby mountains above his small village and playing his recorder, when a crack of thunder roars, and the smell of smoke begins to waft in the air. Fearing something has happened he heads to the edge of the cliff and discovers his village has gone up in flames. Racing back home he can find no survivors, save for a dying old man that can't even tell him who did this.

Upon reaching his own home, his wife Italia lies dying and their son Nathaniel is already dead. Italia gives Cyros the only information she can. It was the Tara army, led by a man in red with a gold belt buckle who left the village clutching the pendant of the village elder before setting off west towards the city of Reed, the largest settlement in the Outlands. She asks him to ride to Reed before the slow-moving army can arrive and warn them of the upcoming attack.

Cyros cannot. Grief stricken at everything he has known being suddenly taken from him, and being nothing more than a mere farmer, he only wants to save his wife while it may still be possible.

The decision is made for him soon enough as Italia passes away.

No need to beat around the bush, it is a pretty cliché opening. Wife and kid killed, nothing to live for, only revenge. We've all seen it before. WiL is just getting started. The basic premise is merely the first step on one of ZZT's grandest journeys. For now, Cyros's interests lie solely in fulfilling his dying wife's wish to warn Reed, and his own goal of striking down this man in red no matter the cost. Time will give Cyros his chance to grieve, and while he will never forget what happened on this day, his story is one of far more than revenge.

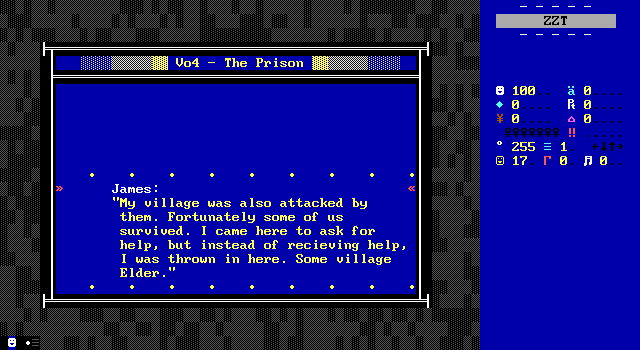

The elder of Reed is disinterested in Cyros's tale of destruction. Not only does he not believe Cyros, but he has the man imprisoned for spreading dangerous stories. Reed has its own small army and if they were about to be besieged, their scouts would have come across the Tara army.

Imprisoned, Cyros meets with two others: James whose village has also been razed by Tara and the real village elder who claims the throne is being occupied by an impostor seeking only power and wealth for himself. The group discuss how to get out of their predicament, until a guard returns to tell them to shut up. Cyros, picks a fight and knocks the guard unconscious. He frees the other two prisoners and after a brief jailbreak sequence of fighting guards and pilfering their weapons the three confront the impostor.

Once order is restored, the elder invites the two to stay in Reed, but both James and Cyros have to decline. James's family survived the attack, and he must get back to them. Cyros cannot rest until he has gotten has revenge on the man in red. The group splits off, expecting to never see one another again.

For Reed, the warnings brought by Cyros and James did not come too late. No longer surprised by the attack, the city of Reed was instead the first settlement to win a battle against Tara. James and Cyros are hailed by the city as heroes for their warning and their restoration of the elder to his rightful place. Word quickly spreads, and soon the names of James and Cyros are known to all across the Outlands with the people left wondering where they've gone and if they'll ever return.

- [1] Also, we're not so dumb these days as to describe a world that's 100% cinema as "not a game" or trying to be pretentious. Nor do we describe cinema heavy games that include moments of more traditional ZZT gameplay to be afraid to commit. The only reason to divide these games into interactive and non is to let players know what level of interaction to expect!

- [2] A #cycle 1 command is executed, but only after the object has been touched. When the cycle value updates, it's too late to interact with the mini-game.

- [3] It's undoubtedly the strangest part in the entire game, and it's game that gets pretty weird. James and Cyros are very off-putting with how they treat her for the entirety of the scene, being very hostile and insulting whenever they have the chance! It got to the point where I assumed these two weren't actually going to be the real James and Cyros.