Robots of Gemrule (Or, "Trouble Beneath The Dome")

Gee! How come your author lets you have two cool names?

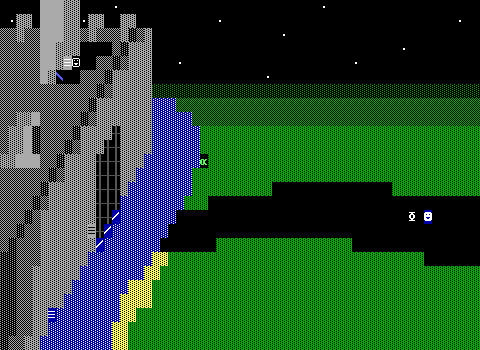

Gemrule, to me, is the Software Visions release that sparks the imagination more than any other. One look at the title screen and you'll know you're in for a treat. The game is still another adventure with a mixture of puzzles and shooting, though by this point Janson no longer needs to bother with macguffins be they purple keys, magical artifacts, or golden coins. This game moves forward through its story, which despite what the game's visuals may lead you to believe, is more involved than most of the era. On a planet populated with robots (move over giant insect creatures), the ruler "Mother Brain" has suddenly had a change of heart and has been shipping robots off to other planets as slave labor! You have been sent in to figure out why Mother Brain is doing this, and to put an end to it.

While "slave labor" isn't exactly going to win anybody over to Mother Brain's side, once the player uncovers the truth, there's some sympathy. Maybe. More importantly, your task will change to saving the planet itself from destruction.

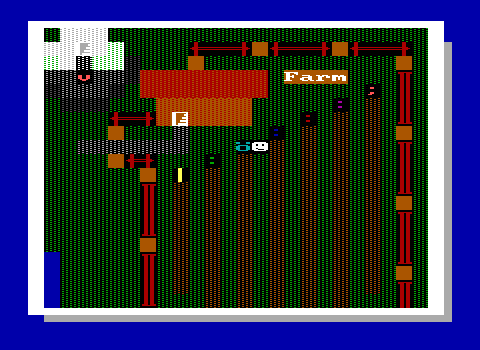

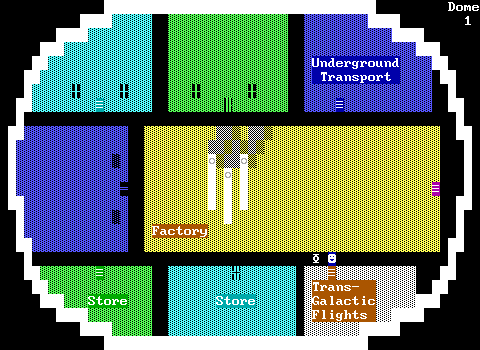

To do this, you'll explore the domed cities, traveling via underground transport from dome to dome, exploring various locations and trying to get to Mother Brain and confront her over her misdeeds. On your journey you'll explore four domes filled with factories, shops, and homes, take a trans-galactic flight to the moon Tycks and hopefully save the planet.

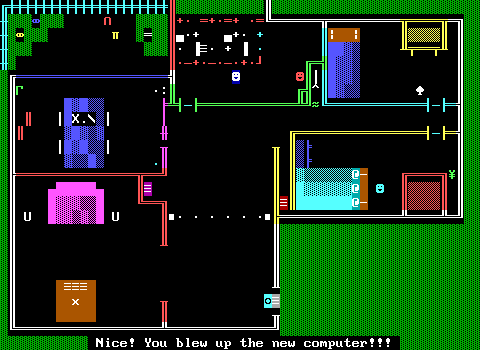

Gemrule features some great aesthetic choices with rounded boards enclosed within a protective glass dome, and building interiors being used as the setting for the usual challenges seen in ZZT adventures. Security systems are more than happy to atomize careless players that don't come prepared. Shops offers not just health and ammo, but useful equipment such a tool kits, a flashlight, and a pass for the local transit station. Money is a main concern of the game, and supplies are as hard to come by as they've ever been in one of Janson's games making this one perhaps the most difficult of all second only to perhaps The Three Trials.

Iconic moments include playing doctor for a malfunctioning robot child, meeting with Mother Brain herself, accidentally blowing up Gemrule, and of course boarding the wrong flight and winding up a slave yourself!

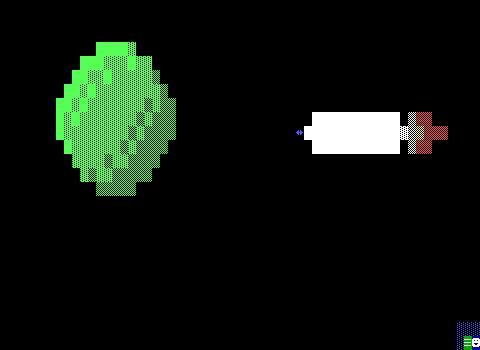

After so many instances of fantasy, Janson's sci-fi adventure breaks away from the forests of lions and centipedes, making Robots of Gemrule the most distinct of Janson's classic adventure titles, creating an imaginative world of robots, mad scientists, and casual space flight. (Well, except for the part where you do just so happen to explore a few boards of forest filled with lions and centipedes.)

Warlord's Temple

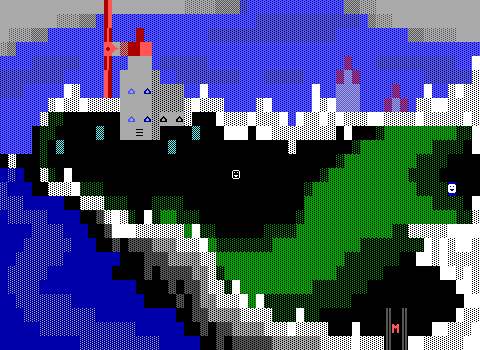

A Matt Williams release, and a classic of its own. Warlord's Temple is an early example of a ZZT world trying to do more. The player explores the temple and its surroundings fighting creatures and gaining experience to learn new spells for the climactic showdown with the dark spirit that has taken the temple as their own. Puzzles are no longer pushing sliders, or pulling levers to move walls. Instead things follow the a point-and-click adventure school of puzzle design of finding items that can be used with other items to progress.

Warlord's Temple is a short game going by board count, taking place over a span of about fifteen boards, ending sequence and all. Playing it however, takes a lot longer than you might think due to the various puzzles that need to be solved. It can take some time just to get inside the temple, and even longer to uncover all of its secrets.

The game is highly detailed for the era as well, being clearly designed with STK in mind from the very beginning, and taking advantage of it to create some very vibrant outdoor environments set against a blazing red sky. The game is quite nice to look at even today, and does a great job of utilizing basic fades to create some very striking boards. In addition, the attention to detail can be seen in some of the objects scattered throughout the temple. Arrows are the player's primary form of offense, and can be found in bundles of two or individually. The game uses a cap on the player's ammo to make fights meaningful. When you only have six arrows to kill anything that moves, you better make them count. Matt agrees, and touching one of those bundles of two when you have five ammo will result in collecting just one arrow with the object changing in appearance afterwards. Many games would have been content to just let the player waste an arrow if they tried to collect both, but Williams doesn't need gotchas to challenge the player and took the time to write the extra code for their benefit.

Once in the temple, much of the game is about preparing for the final battle, with several optional puzzles allowing the player to earn more experience and unlock new spells that will be essential to defeating your foe and restoring the kingdom to its former glory. This is presented as optional exploration, though winning the fight without being fully equipped may depend a bit too heavily on luck. Oh, and did I mention the final battle is a turn-based RPG battle? While frequently overused, in 1996 this engine was undoubtedly an impressive piece of work and the mark of a talent ZZT-OOP programmer.

Of course, even if you can show up to the final fight early, the world is so much fun to explore that there's little reason the player would even want to end their quest before they've seen everything Williams has on display here. Warlord's Temple does quite a lot with a little, resulting in a very polished feeling experience, and one that comes highly recommended.

Code Red

You were a normal sixteen year old. School, homework, friends, music, the perfectly average guy. Until one day. This day you got up the usual way and ate your breakfast the usual way. Then you turned on the TV...

The definitive "Wake Up And Save The World" adventure, and the game that countless imitated but none surpassed. Code Red is arguably Janson's most important ZZT game (not world, we're not counting Super Tool Kit here). ZZTers, typically being teenagers, had a nasty habit of promising the moon and delivering nothing more than hype, with every ZZTer promising something bigger and better than anything in the works right now. Whether Janson pioneered the epic mega game concept or was just the first one to actually pull it off isn't important. What is important, is that Code Red created a template for ZZT worlds so frequently emulated that for years after its release it would be considered to be the greatest work in ZZT.

Nearly thirty years later, the excitement has calmed down a little. Even so, Code Red remains an absolute must play, and is one of ZZT's most enduring games. A game so massive it has eight unique endings, Code Red tells the many possible stories of Kyle Lipschitz, a perfectly average teenager who keeps a rifle in his dresser. Code Red has the distinction of being the first ZZT game to contain one adventure spread across multiple files, utilizing a password system to move between them. The three worlds combine to a near-unheard of size of more than 800 kilobytes of data. The claim of eight endings is selling it short. This is much closer to eight games than it is to eight ways for it to end.

And it all starts in your family's suburban home. The player is treated to a multi-story house oozing with a level of interactivity previously unseen. "You can knock over a garbage can, spill garbage, and then get a vacuum to clean it up" is the sort of promise you'd hear from certain prolific professional game developers in the 2000s, but this describes Janson's creation accurately, no misleading promises.

This detail isn't pointless or just for show. Kyle's actions on the first few boards are quietly tracked and used to determine which story path he gets sent down. Will you grab some breakfast and go back to bed? Will you mail a letter for your mother? Will you unplug the Super Nintendo while your friend is playing and be left to die because of it? Only time will tell. It's the sort of game that after playing on and off for years I'll still randomly stumble across a new interaction I haven't seen before.

Your adventures outside the home can take you almost anywhere. You might go to a nearby amusement park. You might fly to the White House before the president is abducted by aliens. You might visit a TV station. You might get stuck crawling through a sewer maze. (They can't all be winners.) The game's opening plays out as a demonstration of the butterfly effect where seemingly insignificant moments can have a huge impact later on, allowing for quite a number of surprises when Kyle steps outside of his perfectly average family home.

In addition, Code Red is loaded with music. Janson's skills carried over to composing as well, and all of her works have at least a handful of sounds and plenty of sound effects to provide far more to listen to than typical ZZT adventures. Code Red takes it to the next level with several dozen themes consisting mostly of original compositions with a few ZZT adaptations of existing songs as well. Most ZZTers could try to emulate Code Red in terms of graphics or story, but few were up to the task of composing, making Janson's game still stand out today from the numerous imitators.

The game's legacy has ensured that it lives on as one of the high-marks of ZZT. These days the shine has dulled a little. With so many different paths to develop, it's clear some get more love than others. Some paths have lovingly crafted early STK graphics, while others look like the work of an average game of the era rather than a gem. Your actions in Kyle's house don't always make it clear when they've actually had an impact, which makes it a challenge to find all the possibilities without consulting a guide. It can be easy to disregard the game as just being a flashy introductory sequence followed by far more typical ZZT gameplay, an issue of focusing on quantity over quality. In fact, an early demo consists almost entirely of the initial home sequence. These days, the sheer size of the world can be daunting, and without knowledge of what path you're heading towards, those that haven't made the commitment to see the entirety of the three files may wind up picking a lesser path and finding the whole thing to be a bit overrated.

How well Code Red holds up today depends on how much time you're willing to invest and how much knowledge you have of the ZZTing era that surrounds it. By modern standards there are certainly more well-designed adventures with of a more manageable scope, yet the lineage of so many celebrated ZZT games can be traced back to Code Red, making it indisputably one of the most important titles in ZZT's history.

Coolness

...For an example of that lineage, there's Coolness, by Matt Williams.

Your name is Fletcher Long. You have just finished helping your dad, Marshall Long, at his workplace, the bank. You are now free to do whatever you want, using your wits and a small gun that you own. You had better be careful, for there's no idea what type of trouble might befall you this day. This, after all, is a very COOL day........

You can see the inspiration.

Of course, being a fellow Software Visions member, there's no hint of community drama to be had. Janson is even listed as a beta tester for this one.

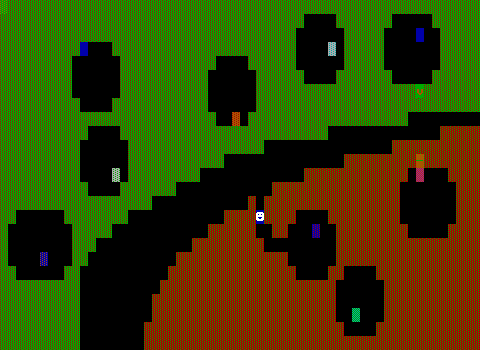

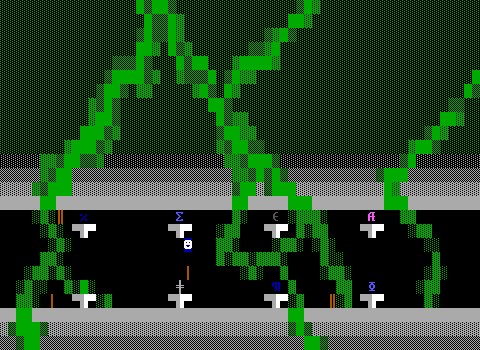

There are certainly a number of similarities, but it's a disservice to Coolness to merely call it a Code Red-Like. Code Red feels like the peak of early ZZT design, while Coolness feels like it's part of the next era of ZZT. Coolness seems to have been developed from beginning to end with STK graphics in mind, resulting in a game that looks more like a game from the back half of the 90s rather than the front. Environments are detailed more via use of color than the immense amount of interactivity seen in Code Red, and the game is more streamlined, with three major paths to take and a total of four endings between them. An issue of The NL, a ZZT community newsletter, mentions the difficulty of actually finishing a game being one reason why Coolness is content to scale back on the endings rather than try to raise the bar even further.

Coolness feels like its own game thanks to mysteries of the world it creates. It likely won't take players long before they discover that Fletcher's father has been keeping quite the secret from his family, you know, in the giant multi-story-high research lab hidden behind the backyard fence. Once again players may wind up going into space, or maybe they'll just stick to the local swimming pool instead. The world feels much emptier as much of Fletcher's travel is done on streets devoid of anything moving, giving it an haunting atmosphere that always intrigued me. Homes are empty, doors are locked, NPCs don't have time to talk, and the amount of interaction is much more limited than Code Red. Even so, there are moments that show that the lessons to be learned from Code Red were indeed taken to heart. Small touches like opening and closing drawers on a desk, and the flashing colors of security lasers give the world a little more presence than it might have had otherwise.

z2 era reviews of the game are generally positive, describing it as a "Code Red Lite", making it more approachable and easier to reach an ending in, especially with the focus on puzzles over action. The pacing is much slower with entire boards being used to depict small environments resulting in plenty of walking from place to place. Fortunately for an early post-STK release, the graphics are quite charming. This is as much a game to soak in the scenery of as it is to play. Very much a game with a unique feel despite the explicitly non-unique origin.

Mission: Enigma

Lastly, we have Alexis Janson's final ZZT release, the other big one, Mission: Enigma. After the success of Code Red and its immense size, Janson was faced with the impossible task of creating something bigger than the biggest. She wisely realized that making a bigger and longer game would be miserable to create. The solution instead would be to simplify. Rather than create something bigger, she would instead opt to see just how much could be crammed into as few boards as possible, resulting in one of ZZT's most well known adventure-puzzlers.

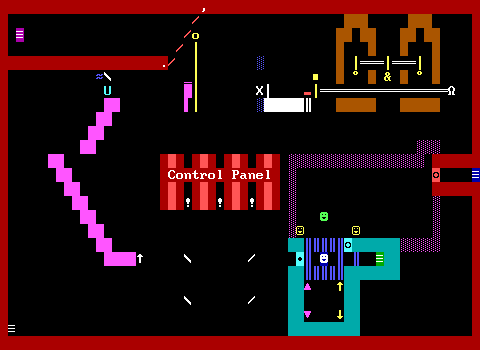

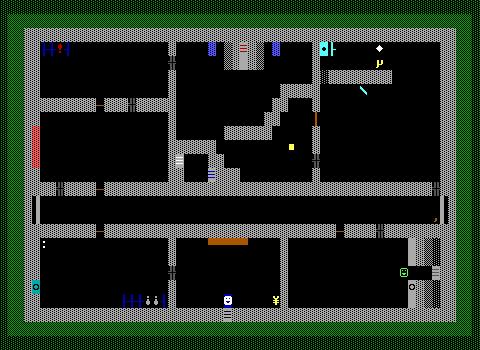

Rather than three files and nearly 200 boards, Mission: Enigma fits everything into a mere twelve boards. On these boards the player will infiltrate an old castle, stop Dr. Kris, match wits with a sentient computer, and catch that fucking knife.

The story is set in the year 2140 with the player acting as a spy working for DOVE in an attempt to find out what Dr. Kris's experiments are and to put a stop to them. Starting outside the castle gates, your first job is to find a way past the lookout guard and get inside undetected. From there, you'll have to fight your way to Dr. Kris's lair, solving a multitude of puzzles and defeating a number of guards. This is a task the player is woefully unprepared for, as to start off they have just six bullets and two torches, yet through their ingenuity they'll manage to emerge victorious.

Mission: Enigma continues the intricate detail seen in Code Red, but this time rather than transform the player's actions towards a particular path, the detail is necessary to progress deeper into the fortress. Visual effects to impress in most games are subtle clues here. If an object exists, it has a purpose. Shard of glass, corks for wine bottles, precious gems, and icy blasts from an all too powerful HVAC system must be exploited if you're going to survive.

This has a few unfortunate side effects that critics of the game are happy to point out. Mission: Enigma is loaded with instant game overs. Missing a shot can render the game unwinnable. Walking too closely to the cold can freeze the player solid. A leaky pipe can burst and flood the room so quickly that there's no escape. It's a rough game that will kill the player constantly, for making even the tiniest of mistakes, and in some cases for simply not thinking the way Alexis did.

Then of course there's the knife. Due to the game's success the knife has become the very symbol of Mission: Enigma's flaws. A deadly trap launches a knife through the air at the player, killing them instantly if it strikes. Unsuspecting players die to this, then reload, and deftly step aside brushing their hands as the knife smashes into the stone walls of the castle and breaks.

...Shortly thereafter the player encounters a guard that can only be killed with that knife that they were actually supposed to catch out of the air. Hopefully they have multiple saves.

Needless to say, a lot of people have been bitten by this over the years and many consider it to be a very ugly blemish on an otherwise quite impressive title. They're not wrong. I certainly don't like how the sequence is handled either, but the knife is really no different than anything else in the game. Everything has a purpose, and nothing is to wasted. This is the ethos that created this game and that is the ethos expected of the player as well. The sooner the player realizes that nothing in Mission: Enigma is superfluous, the sooner they can begin to appreciate just how tightly designed the world is.

Yes, you'll have to save before you do much of anything, but that's good practice in most ZZT worlds regardless. Players that come to terms with the fact that dying is a part of the process will have a much better chance of getting into the head-space the game expects.

Deeper inside the fortress, beyond a point where knife-missers will ever reach without cheating things quickly scale back in terms of how much there is to do. I suppose this is another instance where Mission: Enigma and Code Red aren't so different after all. Later boards tend to be larger individual puzzles, though after getting through the initial gauntlet, it's a bit of a relief to slip back into that more relaxed puzzle solving mode where what needs to be done is obvious and any progress is made explicit to the player.

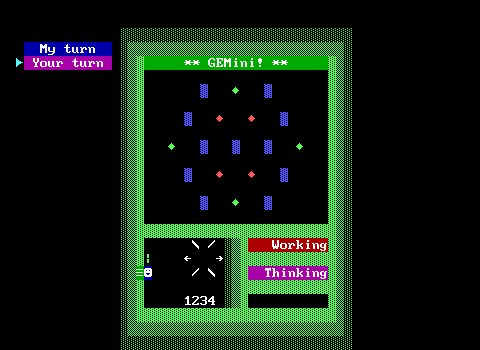

For players that make it far enough, they'll be rewarded with a showcase piece of ZZT programming, the "GEMini" minigame. This is a simple strategy game played on a hexagon where the player and an AI take turns moving their four gems around in an attempt to line them up in a row. It's no chess, or even checkers, but it is quite impressive to this day to see a "computer" opponent in ZZT playing a game like this. As is the case with many ZZT programming tricks, it's more smoke and mirrors than anything else. The computer simply picks random moves and thanks to the small playfield it's easy to look at the computer's decisions and be able to rationalize them as a deliberate choice. It's easy to be fooled, especially with the depth of the initial boards still in the back of the player's mind. Mission: Enigma pushes the limits of ZZT in truly astonishing ways for something so early in ZZT's history.

For years there was debate as to whether Code Red or Mission: Enigma was the superior Janson release. These days we know better than to pit two vastly different experiences against one-another as if they were somehow opponents and that there was somehow a fair metric by which they could be objectively measured. Not every ZZT world should be aspiring to be the next Code Red, nor should they be aspiring to be Mission: Enigma either. Besides! These days we also know that Mission: Enigma is the the superior Janson release.

Teasing aside, Mission: Enigma feels more cohesive, polished, and better designed than Code Red's sprawling "anything goes" attitude. For many years it's understandable for both styles to have their share of proponents. They truly are different games and the enjoyment (or lack thereof) for either has no impact on whether or not you'll enjoy the other. Today, the short focus style of Mission: Enigma strikes me as being more more in tune with today's tastes. It's game that could have come out just this year and still received just as warm a reception, while Code Red comes off as a bit unwieldy. You can, and darn well should, just play both, but if we're turning art into the Pepsi challenge, I suspect the average player today will enjoy their time with Mission: Enigma more.

Again, it's still a stupid thing to debate. Both are iconic, expertly made games, with some of the finest legacies in ZZT. It's a mistake to only support one when we're so incredibly lucky to have both.

While Code Red's impact was on gameplay and story, Mission: Enigma was a much tougher nut to crack by those seeking to emulate Janson's successes. You can witness the inspiration fueled by Code Red by pressing "P" on dozens on title screens throughout the 90s. For Mission: Enigma, its legacy can be seen by waiting on numerous title screens instead.

Mission: Enigma takes ZZT's traditionally fairly static title screen and turned it into a lengthy animated sequence unlike anything else at the time. The entire opening animation is a whopping five minutes in length, revealing characters, showing magic spells, cracking jokes, and making references to the Energizer bunny. After Mission: Enigma, every game had to do basically just this, with many demonstrating the same kind of spells and making the same jokes first seen here. If you've ever found yourself desperately wishing you could just play the game already from a ZZT title screen, you have Mission: Enigma to thank.

Oh, Also...

In addition to including the registered copies of all of these worlds, the ZZT Pack is full of extra text files to help you navigate them. There are the games' official readme files of course. Many games also include a map file that also includes general purpose hints. Code Red comes with a complete solution file that makes it easy to get on the right path to any of the game's endings while also providing directions to see those paths through. It's an invaluable resource for completionists that shouldn't go unnoticed.

A slightly earlier version of the pack (old enough to include the original Cannibal Island) has had its original disk dumped as well. If you're willing to load up DOSBox you can see the original presentation given to these files, with a very MegaZeux inspired interface for installing everything. While most non-Epic ZZT games asking for money felt like cash grabs, there's an astonishing level of professionalism and presentation put into the release. For as often as ZZT companies were just playing pretend, Software Visions was more than capable of convincing you that you were making a purchase from a proper business. It's no wonder that these registered worlds survived while for so many others it's dubious whether or not registered versions ever existed.

To this day, Software Visions remains the most financially successful third-party ZZT company. The quality, ambition, and programming prowess on display went above and beyond expectations of the era, and helped give clout to Alexis Janson's own game creation program MegaZeux, the most successful of all ZZT clones by a significant margin. These games are the roots from which modern ZZT and the entire MegaZeux community stem from. They are undoubtedly some of the most influential and important releases in ZZT, and some of the most important and best examples of what can be accomplished with ZZT. If you haven't explored the Software Visions catalog, it's an absolute must.