Zenith Nadir's Realm

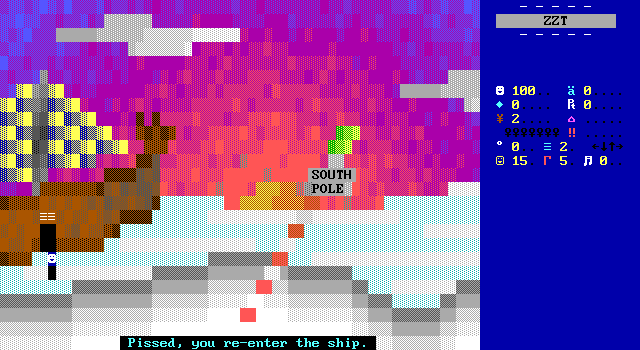

In your search for the fire elemental of

IF, you somehow find yourself in the

middle of a frozen tundra.

YOU: Dude! How'd I get here? And since

when was I searching for a `Fire

Elemental'?

Uhh, you took a wrong turn, and somehow

managed to make your way through a worm-

hole deep inside the Earth's southernmost

continent, Antarctica. And the `Fire

Elemental' is Zenny, fyi. HE IS PYROMANNN

YOU: Ahh, damn! I'll have to find another

hole. Back into the ship, class!!

• • • • • • • • •

Okay.

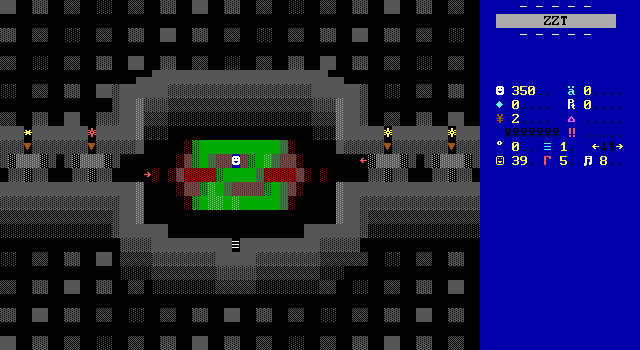

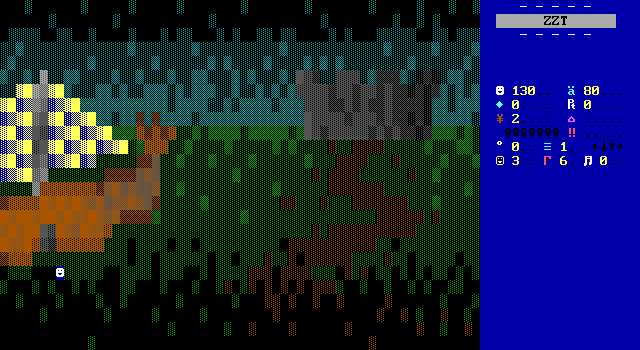

Nadir also is quick to drop the serious plot-line for the opportunity to make a joke of Haplo accidentally landing on the south pole. I can hear it now. Nadir is a ZZTer particularly known for his artwork and this board is no exception. Sunsets in ZZT are frequent, but this is definitely a step above the perfectly horizontal horizon line gradient stretching across each row homogeneously.

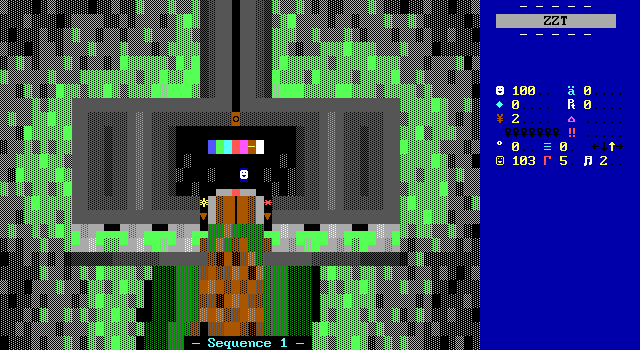

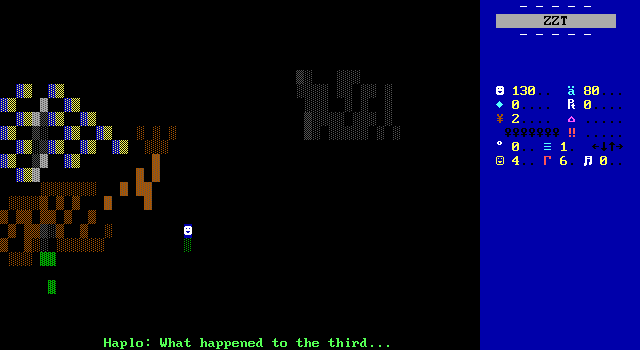

That's better. Nadir's realm takes place in a mysterious jungle temple. The path looks quite curvy and fades nicely into the distance as Haplo approaches. It's almost certainly not going to be serious, but my hopes were high that Nadir could maybe give Haplo something to do for a change.

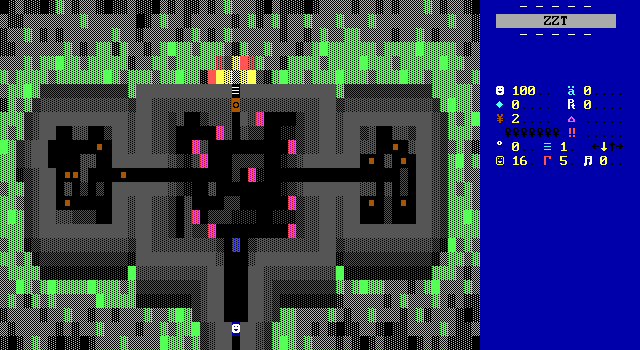

Nadir's temple dungeon offers some authentic ZZT temple gameplay. There are puzzles to solve and monsters to fight. After a lengthy intro followed by a flat second chapter, even playing some Simon seemed like it would be enjoyable.

And so a finger curls on the monkey's paw.

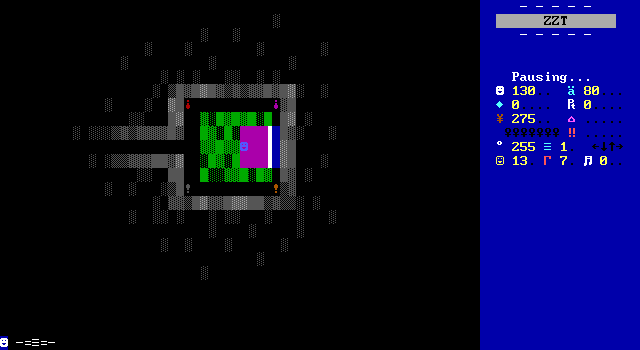

Nadir is far from the first to do a puzzle of this design in ZZT, and I mean, it's Simon. It's not some amazing experience to rush out and tell all your friends about. You press the buttons and move ahead. Except this is brutal Simon. The pattern begins with three notes and adds an additional three each cycle. Each tone plays immediately after the previous ends, which requires you to be incredibly quick at noticing which color flashes. Like Hercules's quiz, making a mistake starts the whole thing over. I wound up slowing down the game's speed so I could write the solution down as I went along. So, while Nadir finally gives us some gameplay, it comes in a form that makes you wish you were back in the realm of Hercules.

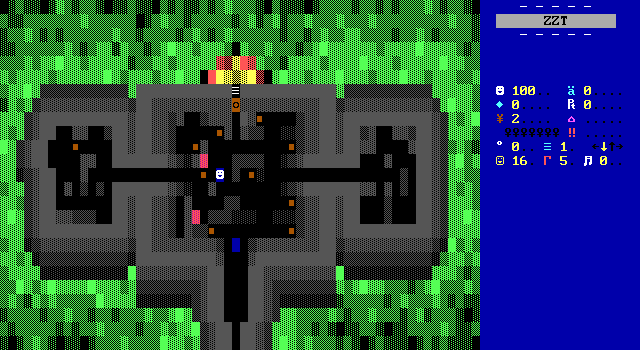

This is then followed up with a Sokoban puzzle. Again, hardly the first ZZT game to do this. This isn't even the first time Nadir's done a Sokoban clone himself. By this point in time, these kinds of puzzles in ZZT worlds have been done so often that Nadir doesn't even provide an explanation for either of them on what you're meant to do. This one fares a little better, as you can go at your own pace, and the way the left and right rooms both funnel into the middle makes it easier to feel confident you're on the right track with each block.

ZZT also offers the slightest of advantages in that you can push multiple boulders at once, which is rarely helpful in such tight corners, but there's a little more leniency in theory than if this were in an engine solely dedicated for this kind of puzzle rather than ZZT.

#if alligned to ensure they're not being cheeky.

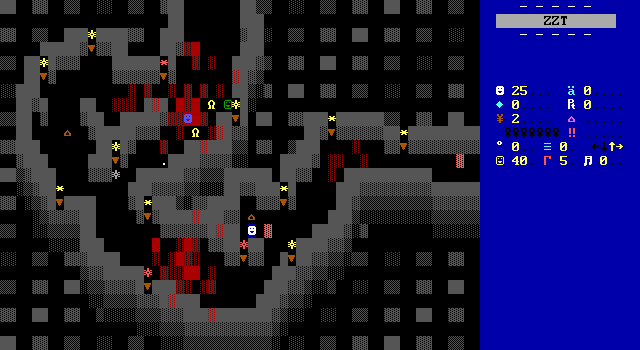

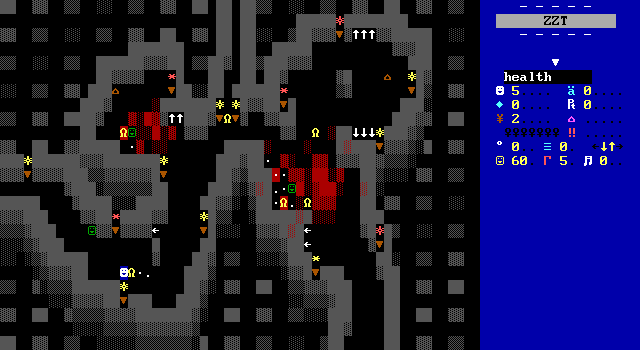

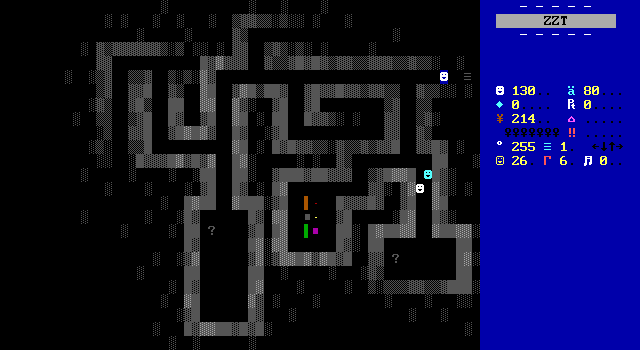

With both of the puzzles complete, Nadir moves things to what he describes as "the action part". This plays out like your typical ZZT dungeon crawler with the player using melee attacks on objects trying to attack them before they attack you. Nadir also adds a bit of nonlinearity within his realm here as there are two paths that can be taken which both lead to the same exit. I welcomed the introduction of some gameplay with a little more meat to it. Nadir's realm is basically a short standalone game itself, which is a welcome change from the lack of things to do in the prior two realms.

Nadir also has a little bit of experience with this type of gameplay in psyche, which plays up the name "Zenith Nadir" by offering a comedic Zenith path and a grimdark Nadir path. The game was well-received, and something I should probably check out myself sometime.

Both paths are close enough that you're not really missing anything. They share enemies and a general aesthetic of irregularly shaped caverns with animated torches set over a patterned background. Enemies include fleas, "ZenClones", and "KingLions". Along the way Haplo needs to also dodge traps like the usual flying darts (an instant kill), arrow launchers, and spinning blades (also an instant kill).

These boards do break away from the Anthony Testa/BlueMagus mold by being solely melee focused and taking place across well-lit boards. Which is superior is a personal preference, though the lack of any extra complexity here means that you run into a situation where every piece of treasure you find is just more health.

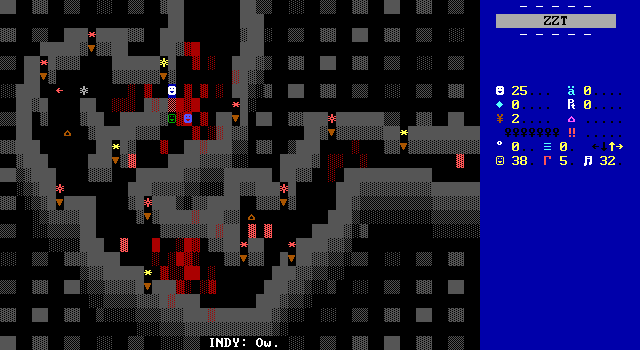

Keeping things silly, throughout the temple you'll find the horribly injured bodies of famous fictional explorers like Indiana Jones, Lara Croft, or "Girl". This is all they have to say, but it's at least fun seeing who gets their little cameo next.

So, this would seem to be a big turning point for the game. It's no longer Haplo safely exploring how to get from point A to point B, but rather him actually having to fight his way through either with brains or brawn. Death Gate is good now, right?

...well.

Unfortunately, much like how combining the talents of several highly skilled and notable ZZTers hasn't worked out, Nadir's jungle temple dungeon crawl extravaganza is also a flop. The difficulty here is way too high and requires too much luck to actually be enjoyable. The flea enemies die in one hit, but the other two are only damaged if they're attacked while being pushed into a wall! In order for attack to land #if blocked opp seek has to return true. This information is never shared with the player, so in practice you're just wondering why objects so randomly do or do not die. They also take four or six hits in this manner to die. Even when you do manage to hurt one, there's zero feedback. No character change, no message, no sound.

It's a disaster to get through this section, and even with all the treasure chests providing plenty of health, I still had to cheat for more.

This is an absurd way of doing melee combat in ZZT. Checking against psyche, Nadir did not do this there, nor is it the case in the Frost series which also features some melee combat sections. What we have here is a failed experiment that takes what would be a much-needed addition to Death Gate and ruins it.

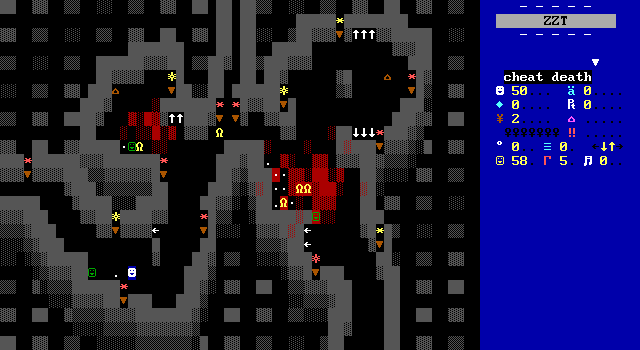

The real saving grace here is that when you die, Nadir coded the objects to stop moving. If you cheat death by using ?HEALTH,

you can wander the board you died on mostly safely. Objects will still wake up if you touch them, which may be necessary if they block the way forward. It all works out, it's just not at all what the intended experience is meant to be, I'm sure.

YOU: Zenith!! I found you! What're you

doing in here anyway?

ZENITH: Agh. I'll come clean. I don't

wanna leave. I'm perfectly happy in this

realm, actually.

YOU: Well, you have to come with me! It's

your duty as an Ancient Council member!

ZENITH: Bah. Fine, I'll come, but first

you'll have to beat me in combat!

YOU: Ha! No problem there.

ZENITH: You'll see...

• • • • • • • • •

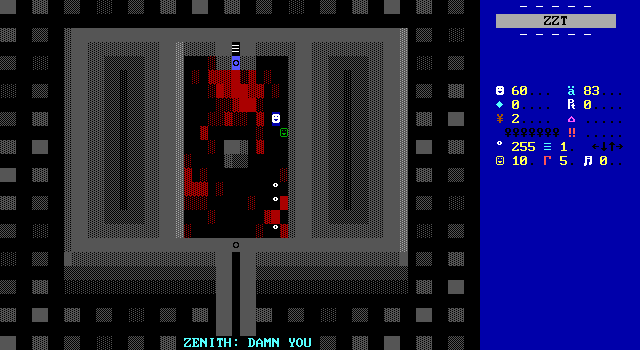

Zenith Nadir is at the end of the temple. Haplo isn't even named here. There's one sentence about Zenith being a member of the Ancient Council and that's all that really ties this realm to the greater storyline. Zenith is also the first person on the council to not just blindly heed the call. This is resolved through combat.

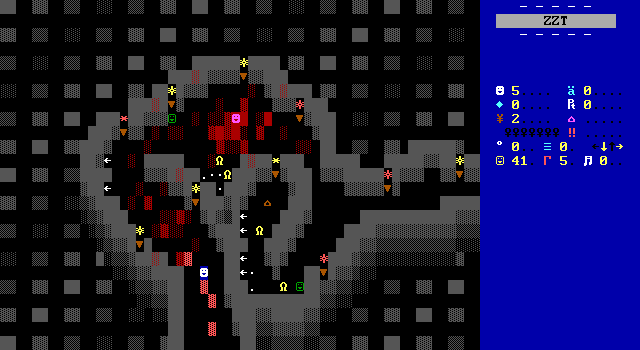

Thankfully, this breaks away from the awful melee system from before. The fight against Zenith is just a run-and-gun shootout. Zenith moves fairly erratically, shooting bullets if he's aligned with Haplo at certain moments, and has one special check for alignment that results in a star being thrown instead. The player receives 100 ammo to fight with, and needs to land a dozen shots. This is also not a very good fight. Because of how he moves, the only real chance to land shots on him is by standing against a wall to increase the chance that moving randomly will fail to move him at all. You basically have to stun-lock him in order to reliably hit him more than once. Either you use this technique and take almost no damage, or you don't and you get yourself killed quickly.

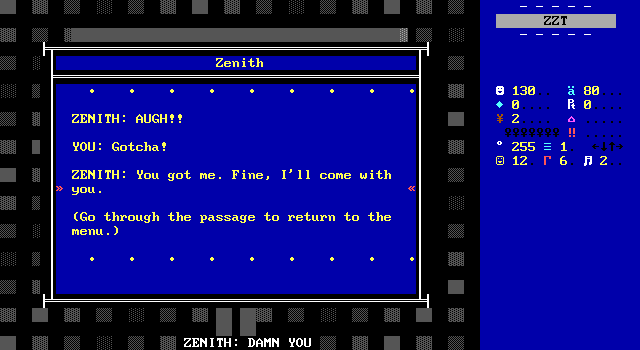

After being sufficiently shot, Zenith gives up and agrees to leave the realm. No cool artwork ending this chapter.

The Verdict

So close, and yet so far. Zenith Nadir's Realm is full of ZZT action staples that could have been worthwhile if they were used effectively. After two chapters of conflict-free walks through pleasant scenery, Nadir shows up ready to provide a bit of challenge and a much-needed increase in excitement. There's effort put into this one, and it goes to waste. Multiple paths and some puzzles are an opportunity to create some memorable moments. This is botched by its terrible combat system and the highly demanding Simon puzzle that instead make it a slog compared to the brisk progress made in previous chapters. Unlike Aetsch's realm, Nadir does at least make something that feels finished. It just still doesn't feel fun.

WiL's Realm

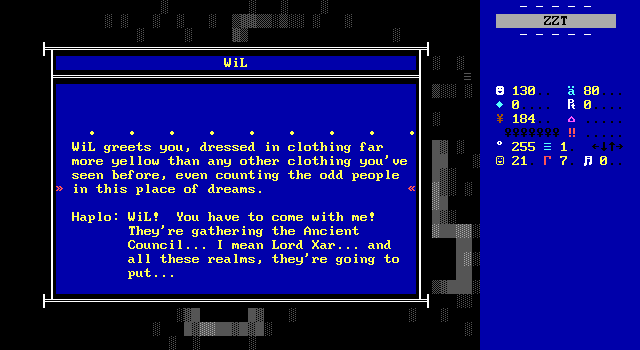

With that, it's time to enter the final realm by WiL. Like with Zenith Nadir, I did have enough familiarity to expect something worthwhile here. At this point though, putting all my hopes on WiL feels unfair to him. It's too late to go back to being a hard fantasy with the grave seriousness of the fractured world and the war between Sartans and Patryns. Both Aetsch's realm of sauerkraut and plastic explosives and Nadir's realm of killer fleas and Zenith clones saw to that. He could also play it silly, of course, continuing to undermine whatever vision Death Gate originally had.

I wanted it to be good for my sake rather than the project's.

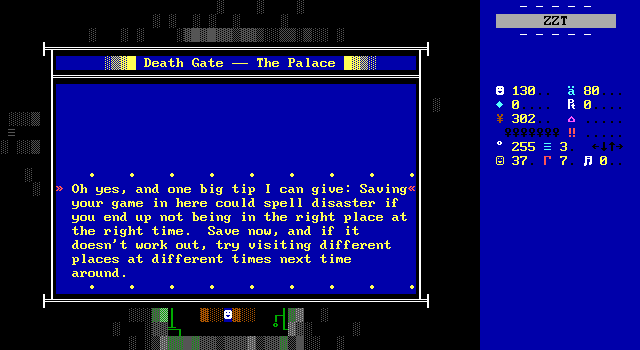

WiL is of course a showman and opens things off with a clever cut-scene in which the player is pushed along a path, breaking away from the usual ZZT cinema standard of sticking the player in the corner and watching as thing unfold. Haplo heads towards a nearby castle that has no visible entrances, but is quickly caught by one of the occupants of the unusual palace.

Sure enough, ZZT is unresponsive. You are totally locked down here unable to perform any actions. The trick WiL has up his sleeve here is to have modified the player to be the normally inaccessible cycle zero. Every time ZZT checks to see what stat elements should act on a given tick, cycle zero elements are skipped over. Needless to say , making the player cycle zero doesn't happen very often. In fact, it only works here because the board is entered via passage, which starts the game paused and allows that player to move once to unpause before returning to the usual stat loop and being stuck.

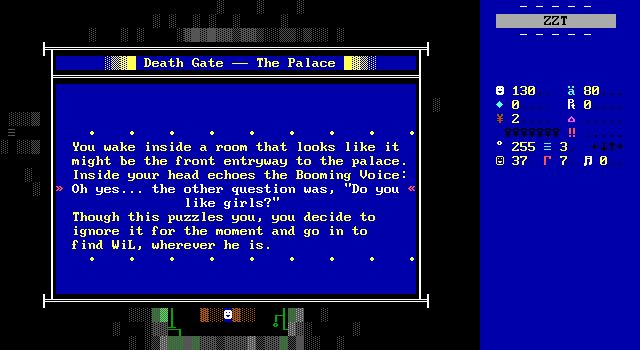

The mysterious voice requires three questions to be answered. Firstly, by asking who it is that wishes for an audience with their master. Hey, just like that, WiL is making his realm connect to the main plot as Haplo namedrops Lord Xar, the council, restoring the world, and even The Sundering. Good job WiL.

Haplo is forcibly put to sleep as the screen fades to black. A player clone is produced next to an invisible passage with instructions given to move left which warps to the castle interior.

WiL's realm has a surprising amount of light exploratory themes of gender and sexuality packed in during an era in which it's wildly unexpected to see such things in a context that isn't meant to be played for laughs. In addition to its ambitious philosophy, it's also ambitious in structure:

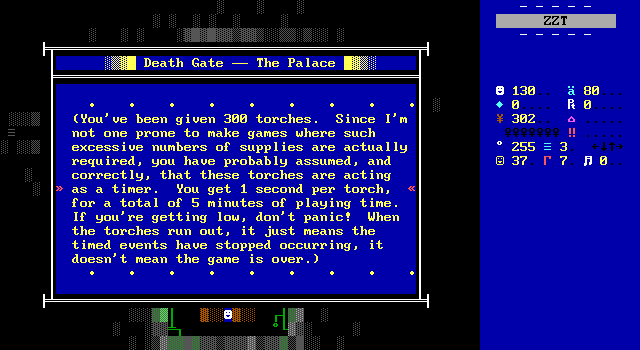

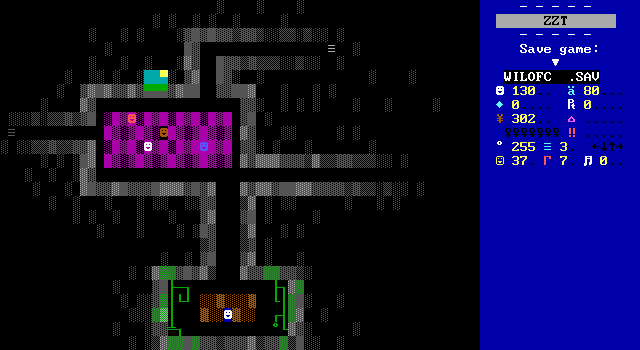

The realm is rather experimental in nature, taking advantage of its status as a smaller piece of a larger project, which allows WiL to create something that can't really scale to a full game in ZZT, but which can be done for a few boards. WiL's realm is designed around people coming and going in real-time. Torches are used to track the current time and objects will appear and disappear as if the NPCs were off doing their own thing, with nothing more than chance meetings with Haplo.

When time expires, the final state of every object becomes permanent, offering a potential saving grace to maybe clean up any loose ends with whoever happens to still be around. The idea here is that your exploration will mean you have reason to go back and forth across a few boards repeatedly.

However, while innovative, this structure is a fragile one. You can not only find yourself in an unwinnable state, but not even realize it. A dead man walking scenario is a pretty nasty thing amplified by the fact that while the timer is five minutes in length, it won't be decreasing when you're reading text. It's hard to say offhand how much time may be lost by having to restart the entire palace sequence from scratch. Death Gate's two more negative reviews (I mean, they still give the game a 3.0 and 3.5 out of 5.0) harp on the frustrations of this realm. Meanwhile, I got through it just fine, only making a mistake on the final scene and just restoring from there. The exact timings are of course hidden away, so I can't say if I was just lucky to avoid frustration or if these reviewers struggled with something that shouldn't have been a struggle to begin with.

The theme of finding others and learning from them. of course, means that this realm is going to be rather dialog-heavy. The story told here, however, has little to do with the council or Sartans or anything like that. It's a brief vignette that could have worked just as well as its own small release.

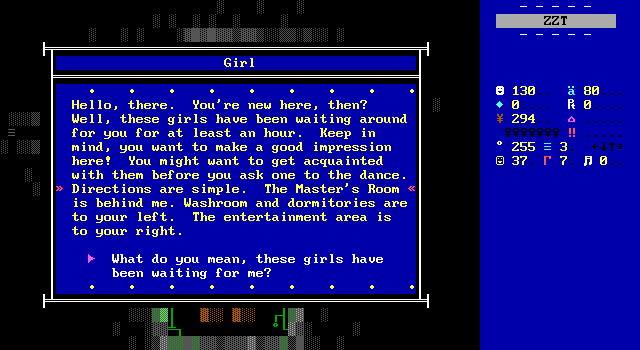

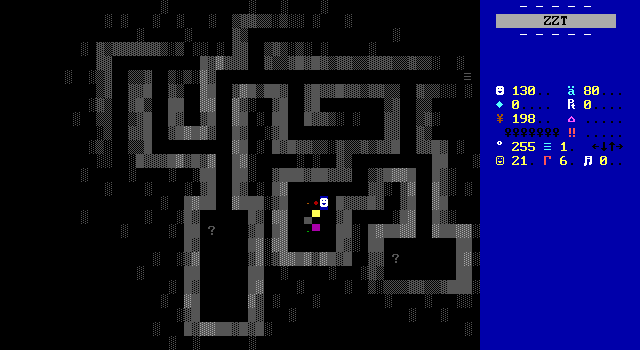

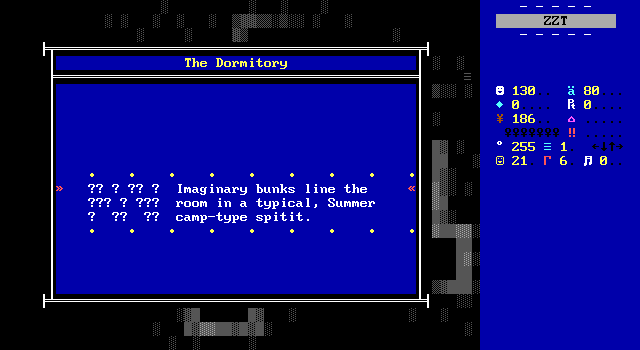

The palace itself is rather small, consisting of four boards in total, with one locked away until the final scene, and another only having reason to visit once. To some degree this undermines the unique timing mechanic, as being in the right place at the right time means being on one of two boards. The central hub here consists of a small greeting area currently populated by a small group of women. To the north lies the master's private chamber. To the west are the bathrooms and dormitories. Lastly, to the east is the ballroom.

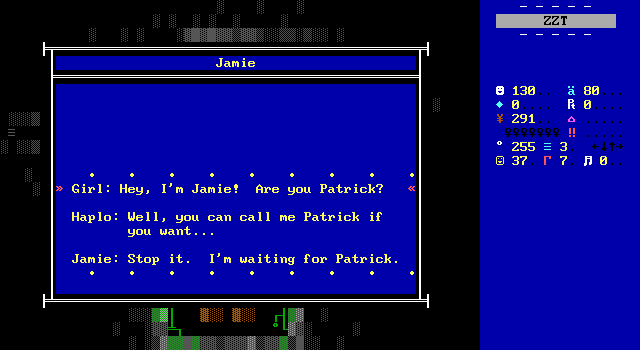

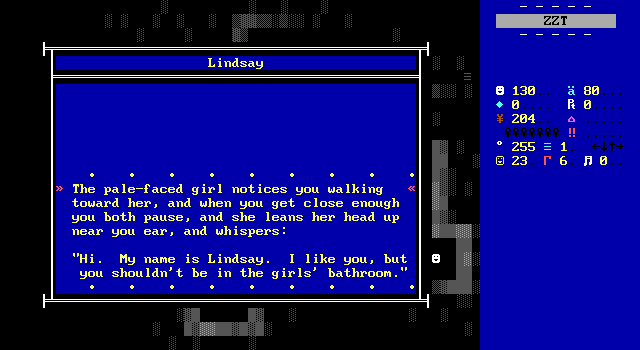

Much of the realm is based on socializing nicely. One of the girls mistakes Haplo for somebody else before realizing she should be sending him directly to the master so that Haplo's trespassing in the realm can be properly dealt with. Haplo describes the scene a little before actually speaking with them, surprised that the women are a perfectly average-looking bunch rather than some harem of unmatched beauties.

Despite not being particularly impressed with their physical aspects, Haplo nonetheless is more than happy to make a shitty attempt at flirtation and instantly gets shot down.

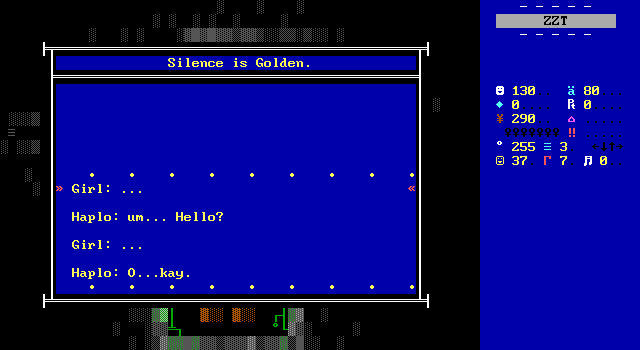

Another girl is silent. Perhaps she overheard Haplo's haphazard wooing.

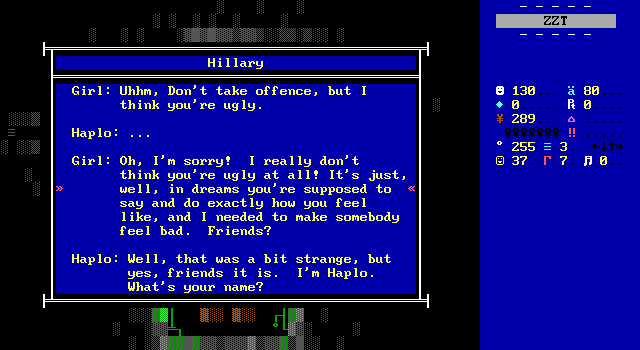

Lastly is Hillary who reveals the conceit of this palace. She immediately turns the tables and calls Haplo ugly to his face. This isn't because she thinks of Haplo as ugly, but because she felt a need to make somebody feel bad, and dreams are all about doing what you feel like.

The master's chamber is where much is revealed. Haplo isn't dealing with WiL here, but rather the same girl who give him a quick rundown of the palace just moments ago.

"Do you know where you are?"

Honestly, you answer only that you know

you are in WiL's realm, or at least in the

realm where WiL can be found.

"This is the realm of dreams. Here I am

master, or mistress, as the gender forms

would dictate. I can exist in more than

one place, as you have seen. I cannot,

however, deal with trespassers."

• • • • • • • • •

The previous events begin to make sense. Haplo had to be put to sleep in order to be able to enter the palace. The master uses the masculine "master" over "mistress" (sometimes!) while using she/her pronouns. None of this is dwelled on, nor is it a big deal in the least. It is, however, something you'd be hard pressed to find in the cis-boys club of ZZT in the early 2000s, and its existence is a delight.

The master goes on to ask Haplo why he trespassed, and learns all about Xar, Haplo's quest, and why he must speak with WiL. She admits to being aware of this due to clairvoyant dreams, but insists that Haplo has still trespassed, and as such she won't give WiL her blessing, making it up to Haplo to find WiL and convince him to meet with the other reincarnations of the council.

Upon returning to the main hall, everybody has left except for the silent girl. Heading west leads to the dorms and bathrooms, though in practice these spaces are incredibly undefined. Other hallways fade to black and prevent Haplo from exploring more of the palace. This being a world of dreams, I had assumed they might be tied to the clock or story events, but that's not the case. What you see here is all there is to see of the rest of the palace, which again makes me wonder how easy it is to actually miss any events.

Haplo, why are you so bad at interacting with women?

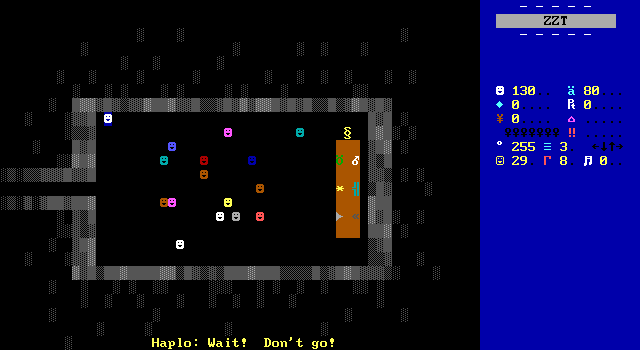

The men's room, of course, has sparkling colorful lights flickering in the middle of it.

Some rooms have question mark objects that offer a description of the contents. It's a rather unusual approach for a ZZT game to not portray the contents of a room through the artwork. I suppose this is the dream theme coming into play, as the dead ends describe themselves as halls leading to "a place you have not yet imagined". Perhaps everybody perceives these rooms differently?

Fooling around as I did worked out, and WiL soon made an appearance, giving Haplo the chance to explain everything to him. WiL finds it unlikely that they'd all be able to mend the realms together. He points out there's no way it will work as there's no way the entire bunch could be convinced. He explains that he himself has no intention of leaving. WiL (the character here, I must stress) believes that his realm functions as a place of peace and that the pleasant dreams here provide more than a unified Earth could.

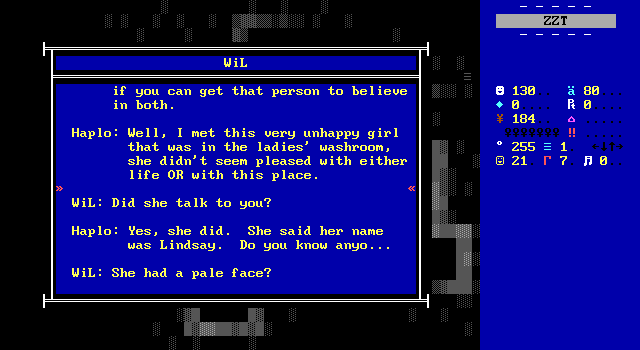

Haplo counters with a dare to prove that dreams are less important than the reality that sparks them. WiL agrees to a deal where if Haplo can find somebody who is having a bad time in their real life while also not liking dreaming he'll hear Haplo out. Furthermore, if Haplo can convince that person to believe in the chance of a good life and believe in the power of dreams, he will agree to go with Haplo on the spot.

Haplo immediately brings up Lindsay, the girl he met in the women's bathroom, which is pretty wild because I suspect most women don't seem happy when a man barges in there and starts striking up conversation.

Still, WiL is rather surprised and impressed. Lindsay has been totally mute to everybody since she arrived. Haplo hopes this is enough to get WiL to go with him, but WiL believes that nobody will be able to find her to help her after the world is combined again. Instead, Haplo has to help her now before the realms can be reunited. His goal is now to bring her to the evening dance and convince her about the promise her life has.

Back in the lobby, some new faces are there. Georges offers the simple advice that the best way to convince somebody that you like them is to give them a gift. The other, Nancy, talks about how the dream realm was actually cooler before WiL and the mistress took over. Another boy named Jes confesses to stealing some of the sparkles from the men's room which apparently are not supposed to be touched. Whoops. Jes offers some to Haplo who expresses interest in them being a gift. You can probably tell where this is going.

There's a little more back and forth between the two rooms as the timer clicks down with at least one more person to speak with though they don't seem to provide anything needed. The timer system makes interactions very opaque and perhaps some of these minor characters are just intended to be hints as you simultaneously make your way through the actual interactions. Maybe it's possible to miss out on Lindsay and thus being able to deal with WiL and these characters serve as last minute reminders to give the player something to look for.

Of course, if that's the case, there's little that can be done. If a person isn't available to speak with, knowing you need to find somebody to invite to a dance or find a gift won't do you any good. I'm still a bit lost as to how one would actually break this system and render it unwinnable as there are honestly only a few people to actually talk to and it's very easy to just talk to everybody on one board and then move to the next, alternating between the two until time is up. There really isn't any rush from what I can tell.

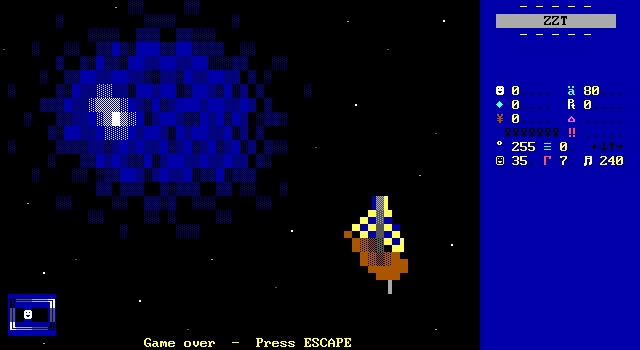

The dead man walking scenario is at least hinted at, though it's rather pointless of WiL to let the game proceed when he's aware this is the case. One last girl that appears is excited when the dance starts and asks Haplo to join her. If Haplo has met with Lindsay he'll turn her down. Otherwise, he agrees to go with her but comments on how he feels like he's missing out on something. This will eventually lead to a proper game over at the dance, but it may give the player the wrong idea that there's something they can still do during the dance.

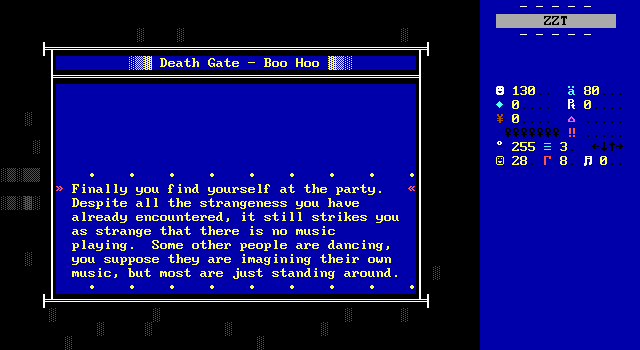

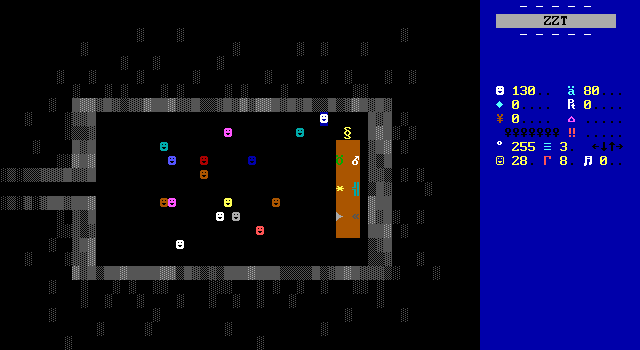

This dance sucks. There is no music playing. Even by this point in time, WiL had a well-established reputation for his compositions with the 5th edition of #play having been released earlier this same year. Death Gate's title screen theme music is actually credited to WiL. WiL is of course under no obligation to compose piece after piece, and here the lack of music is even called into question by characters at the dance themselves making it clearly a cheeky and deliberate stylistic choice for the dance to be silent.

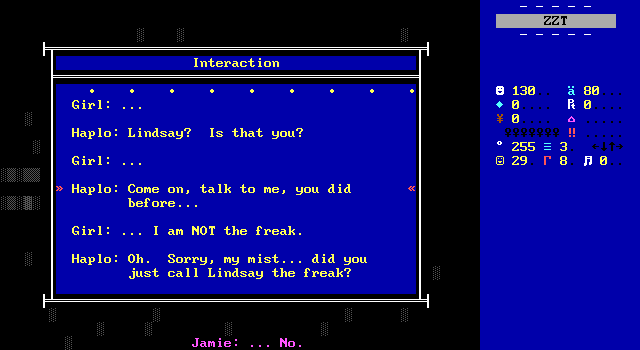

But then, drama! Another silent girl is mistaken for Lindsay and this girl makes it very clear that she does not welcome the comparison. The two get into a tiff with Haplo defending her worth as a human being regardless of how much she may speak. The other girl is not swayed and simply dismisses Haplo remaining unsympathetic.

The reason it's so hard to find Lindsay is that she isn't actually there initially. Her object is kept invisible in a corner until some time has passed, and even then she doesn't reveal herself until the player becomes aligned with the object. Due to the layout of the dance board, what's most likely to happen is that Lindsay won't show up until Haplo aligns with her vertically by attempting to leave the dance entirely. With the scenario announcing that you may potentially get stuck, I wonder if anybody ever assumed they messed up in some way by just talking to everybody and not finding Lindsay.

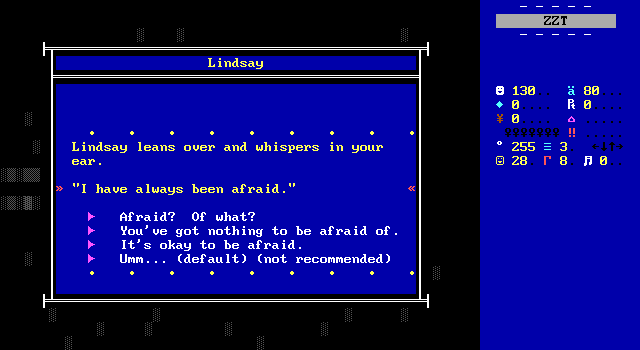

While Haplo is ostensibly doing this solely to get WiL to come along, I think he receives enough characterization through his conversation with Lindsay that their connection feels genuine. This puzzle is basically a guessing game as the player tries to understand how Lindsay feels and what might get her to open up. Sometimes multiple options will continue the conversation, while at other times, one is correct with the others causing her to give in to her fears and leave.

WiL's literary prowess here shouldn't be understated. Haplo is pretty much a blank slate outside of the introductory sequence and neither Aetsch nor Nadir really attempted to give him any personality at all. WiL meanwhile has provided Haplo with empathy and done so in a sincere enough way that when you do make a mistake and cause Lindsay to wake up and thus leave the dance, Haplo's cry feels like it comes from genuine concern for Lindsay and not a recognition that he just blew his best shot at convincing WiL to join him.

With one last roadblock to make sure Haplo picked up the stones as a gift, Lindsay is convinced Haplo is genuine. I like the little philosophizing here. It's refreshing that this doesn't boil down to "a boy was nice to me so now I'm no longer shy". You do have to be honest with her that it takes time and effort for people's perceptions of her to change. That she needs to take initiative herself, talking with others like she does with Haplo to get those people to see what she has to offer. At the same time, other conversations show that this isn't her individual responsibility alone. Others need to extend her respect as she is in order for her to be able to blossom into her positive aspects. It may be true that most people want little to do with the girl who never says a word, but Haplo makes it clear through his own conversations that not fitting in by no means makes her worthy of ridicule.

With her leaving happily and with a promise to believe in herself because Haplo believes in her, WiL agrees to go along. There's an extra cut-scene of the two boarding the ship that recycles the opening cut-scene. Except this time the player is indeed in the corner and watches along as normal rather than the cycle zero shenanigans seen prior.

The Verdict

I genuinely have no complaints about this one. While it might still not fully integrate with the fantasy theme Hercules tries to establish, the realm being one of dreams allows for WiL to be more playful in his scenario without straying into its own thing entirely divorced from the plot of the game as a whole. The timer idea is an interesting experiment that I am really unsure how to feel about overall. In my personal experience I didn't notice it at all really. I never had to wait for something to do, but because of that I'd also have completely been unaware it was even a thing rather than a series of linear events to follow that makes characters come and go. Ultimately that's what it is, just tied to your torch count instead of flags as the player goes from object to object. The reviews out there for the game, however, did seem to run into trouble with it, and given that a smooth experience with it doubles as one indistinguishable from it not existing at all, it's probably an experiment that ultimately wasn't contributing enough to justify itself. However, a tiny set of boards in a collaborative world like this is also a great place to be a little more experimental. No harm was done by including the system (to me), so while I don't think it benefited the players, I'm sure it at least scratched an itch for WiL.

The writing makes this realm significantly more interesting to play than any of the others. Had the other contributors been more grounded in the world Hercules was creating, perhaps Herc's own realm would hit harder in the long run. Instead, it's the first chapter of a book that never got written. WiL's spin on things is still thematically attached enough that it would be fitting in reasonably if the other realms were more aligned with Herc's ideas, but still maintains enough uniqueness that it can hold up on its own as it ultimately has to after Nadir's and Aetsch's realms.

If I had defied the order presented in the game's main menu, and managed to go from Hercules to WiL, I'd simultaneously be more impressed with what Death Gate was doing while also being far more let down by the other two realms. Instead, WiL's realm got to serve as a reward for sticking around to see the game to its finish.

The Vortex

Finally, once all the council-members have been collected, access to "The Vortex" opens up. This is a single board cut-scene that makes up the game's ending, not a final chapter. Since the player is free to complete the last three realms in any order, it just has to have its own spot on the main menu in order to easily funnel the player into it.

The finale is hardly worth the effort of seeing it. "Reuniting the world" isn't exactly an easy thing to portray in ZZT, but this feels like a rushed cut-scene to just get the player out of here already. The little objects connect once more and everyone lived happily ever after. I wonder if Hercules had originally planned for Lord Xar to have an ulterior motive as in the books or if he was content to just have everything work out for everybody. I still would have liked to see the effects of this ritual in some form. This would have been a nice opportunity to have each member of the project submit an ending screen providing an epilogue or even just a glimpse at what the people of each realm are up to. The one constant in the abilities of all the authors of this game is in making some solid artwork. Admittedly, though, half the realms lack characters for the player to really return to. I'd love to see Lindsay making friends or Harazi flying in his balloon over a whole new world. With Aetsch's realm, our only other character is an old man who could be eating more sauerkraut? Nadir's only other characters are dying adventurers that exist as jokes and nothing more. I suppose there's only so much one can do.

Final Thoughts

An inspiring disaster of a game.

I feel like every ZZTer had to learn the hard way of the difficulty of creating group projects like these, learning that there's a tremendous gap between enthusiasm at the idea and actually getting somebody to create something. It's always so easy to just ask a room of people if they'd be interested in participating only to realize that nobody actually will. There are some things that Death Gate has going for it that many other ZZTer group project concepts did not. Firstly, it's being arranged by Hercules and Hydra of Interactive Fantasies. There's significant clout there compared to other projects like 2008s Collabyrinth (not to disparage Nupanick's attempts, it just has the rarely seen aspect of there being a project dump available). Second is that it's a flexible concept. While four realms are absolutely enough to let the game's story work, it could easily have worked just as well with a dozen or more. You don't need everybody who says they'll contribute to actually do so. Third is simply the good fortune of the timing on this game. 2001 is perhaps when Interactive Fantasies was at its peak. ZZTers were still very much interested in making ZZT games and not just participating in community social spaces. This is your best bet to get people actually onboard with this.

Alas, good intentions don't mean a quality title. The reality here is that Death Gate isn't a particularly rewarding experience. It seems to have trouble from its conception and those troubles are reflected in the submitted realms. Nothing feels cohesive, making the game feel more like a series of vignettes with little in common beyond playing as Haplo and a ZZTer getting on a ship at the end. The story established in the beginning feels like it has no impact on the chapters of the game beyond the first. This could just as well have been a world designed for Interactive Fantasies members to combine smaller, more experimental projects into one world for increased visibility. Every realm in this could have fit right into a ZZTV channel: Herc's as a demo for a game properly based on Death Gate the game/book; Aetsch's as a project dump of a surreal adventure game; Nadir's as a mini-dungeon crawler built for the channel; and of course, WiL's experiment with incorporating time into what options the player has available. WiL's could genuinely have functioned as a small standalone release honestly.

Death Gate starts out as a potentially interesting fantasy game before two of the authors toss most of it out the window. With tweaking, Nadir's realm could have been serviceable and I think that or a lengthier Aetsch chapter would be enough to make the game overall worthwhile even if you're really getting very little of the actual "Death Gate" concept. Instead of Herc's chapter setting the standard for what to expect in each realm, it winds up feeling pointless, laying groundwork for something that never gets made. This just leaves us with WiL's chapter, which breaks the mold enough to be very much worthwhile, but it's dragged down by the rest of the game. You'll have the most fun with this game by just editing it to start at WiL's chapter and going from there, and if only one contributor to a group project contributed something of value, there's no need for there to have been a group project in the first place. Death Gate shows that a ZZT game can't coast on name recognition alone (though if you read the initial reviews, it certainly did for a little while). The star-laden author field only makes for a bigger disappointment here. Whether the issue was too little time, too little information provided to contributors, or just a lack of experience in organizing a group effort, Death Gate is unable to rise to its potential as either a straight-faced conversion of the source material or a showcase of what a group of ZZTing all-stars of the early 2000s could do.