Introduction

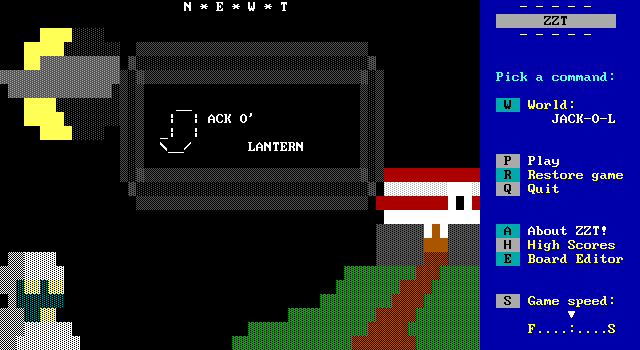

Twenty years ago, on Halloween itself, I released Jack O’ Lantern. It’s a short Halloween adventure game that aspires to horror. As a holiday-specific game, it’s in surprisingly rare class of ZZT games.

I made the game, so even now when I play it, I see certain things others don’t. That’s true of anything anyone makes, I expect, but I feel like this game in particular has secrets that glare at me from every board that no other player could be privy to. Jack O ’Lantern is a sort of conversion or port from a game that has never existed anywhere except in my own mind.

That statement arguably applies to a lot of the games made in ZZT--and maybe even more broadly to a great swath of creative works, distorted actualizations of ideas in someone’s mind. But it’s especially true here. In a sense, Jack O’Lantern was the ZZT game I spent the longest time developing (until my release of Nibblin’ a few weeks ago), because I had initially drawn up plans for it even before I discovered ZZT in the summer of 1997.

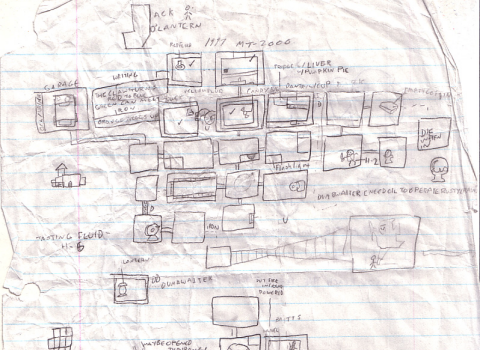

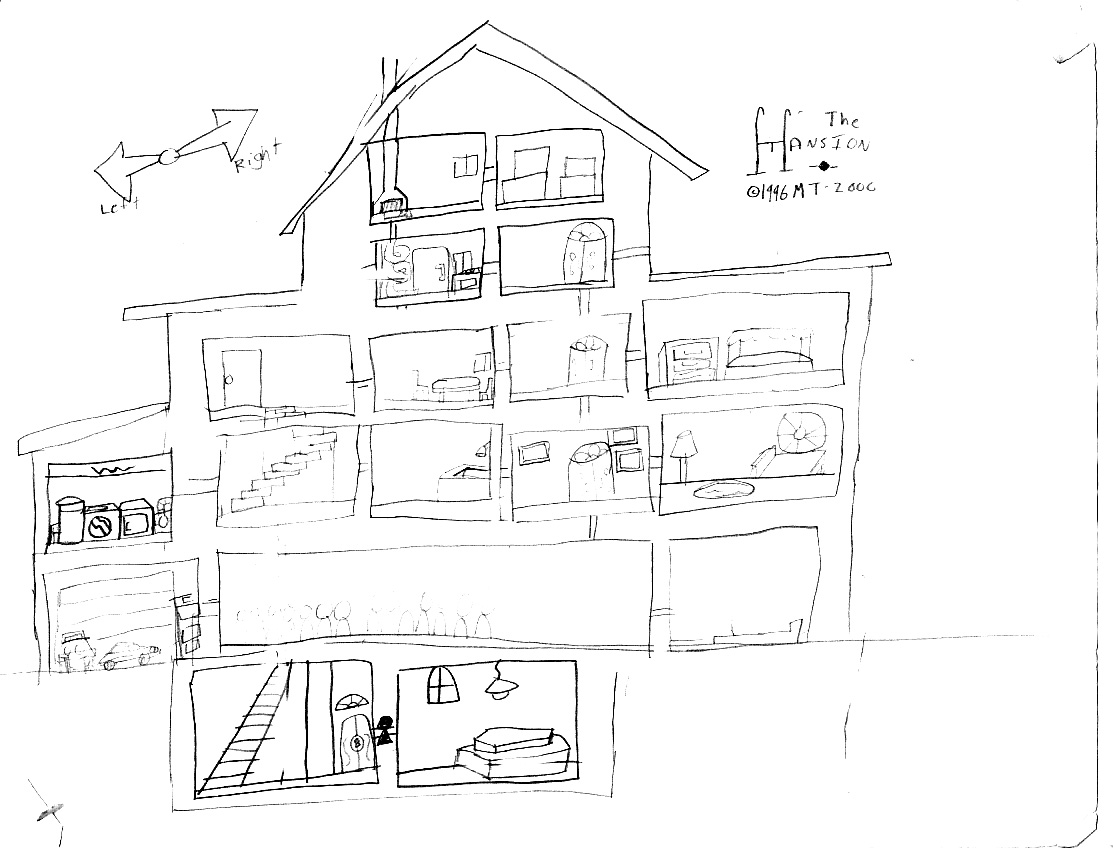

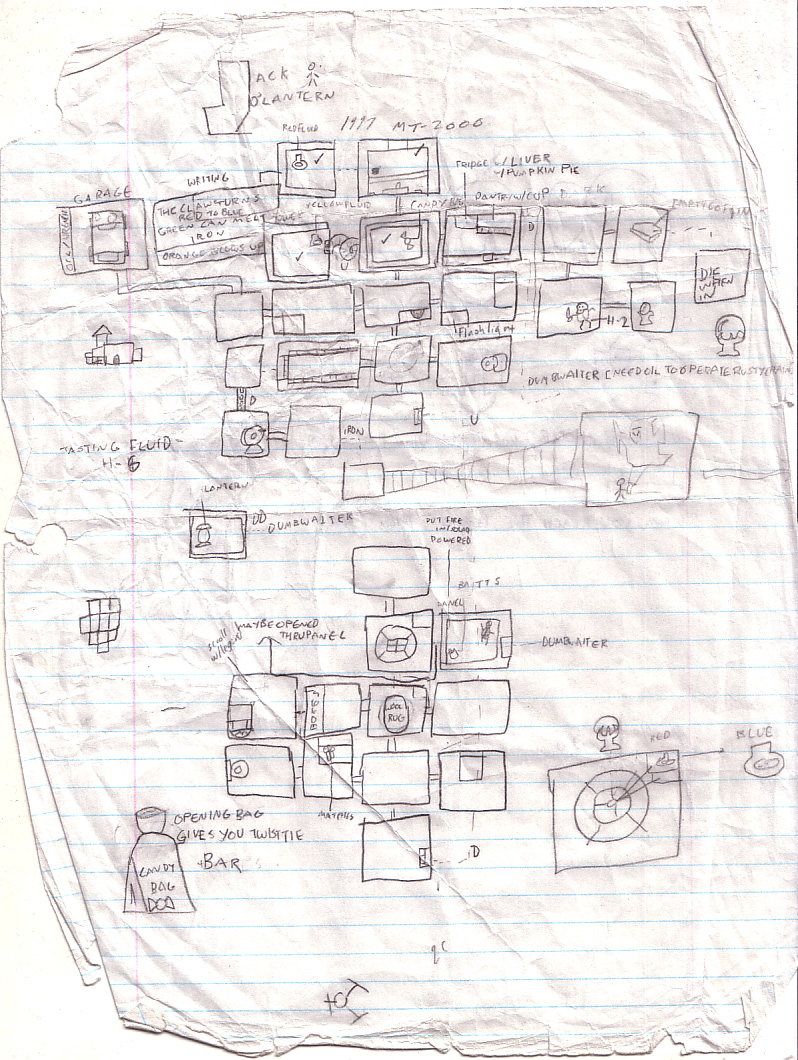

Before I embarked on creating this ZZT game, I had finished a complete design for it as an intended QBASIC text adventure originally called “The Mansion,” the earliest version of which was conceived in 1996 and planned to be released by my bedroom programming outfit, Moore-Tech 2000.

The game’s systems, inventory, and map fully existed on paper, though in terms of programming I only ever scratched the surface of the stage where I was adapting the text parser and inventory system from a previous project. I don’t have most of my old QBASIC files anymore, but I think I really only ever got as far as designing the same ASCII logo that graces the ZZT game’s title screen. Anyway, this is the complete floor map for the game’s mansion in the last document I have for the QBASIC version, still planned for Moore-Tech 2000.

When I set about adapting the aborted QBASIC game for ZZT I used the very same design documents to structure it. It was in a very real sense a faithful port of a text adventure that doesn’t exist.

I’m not sure exactly when I started development on the ZZT version. I think it was in the spring or summer of 1998. It’s impossible to say now, but I’m pretty sure it began before any of the games I released over the summer of 1998--Parallel Universe, The Punctuation People, and Night Conjure--meaning that it spent a longer time in active development than anything else I had made up to that point.

Earlier this year, I watched an archived stream of this game recorded by Dr. Dos in October 2017. There are some weird things in the game that seem baffling to most. But I know why they’re that way. The maps and plans I’d made are still in my head. When I look at a board from Jack O’ Lantern, I see it on multiple levels, from what was intended to what is there.

One last thing before we dive in to the Closer Look-style play by play: In 1998, I was fifteen years old and had hardly seen any horror movies and had not played a single horror game.

Title Screen and Splash Screen

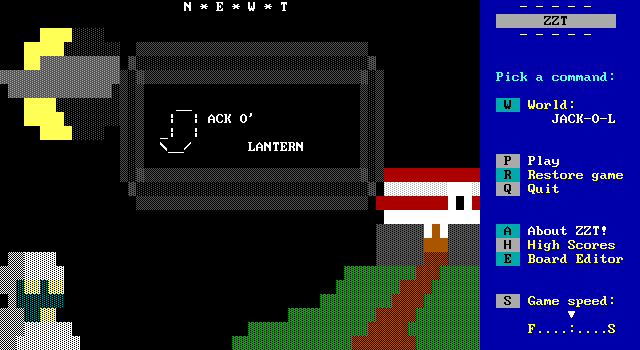

The title screen has nothing flashy on it. Nothing moves and no text scrolls.

Now’s as good a time as any to address the fact that this game’s title doesn’t really make sense except to flag it as a Halloween game. There are no pumpkins or jack-o’-lanterns anywhere to be found. There’s no guy named Jack O’ Lantern. The title screen attempts to set an eerie mood with the oversized moon, ominous walled house on the hill, and the mysterious figure in the lower left. Who is that? You won’t see the character--a ghost--again until the third-to-last board. It’s supposed to be a creepy tease of things to come, but now I’m skeptical it comes across that way.

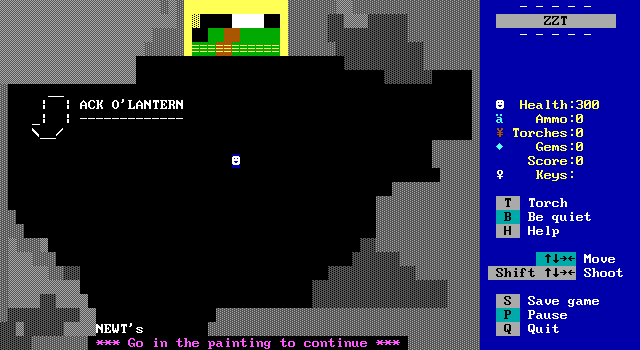

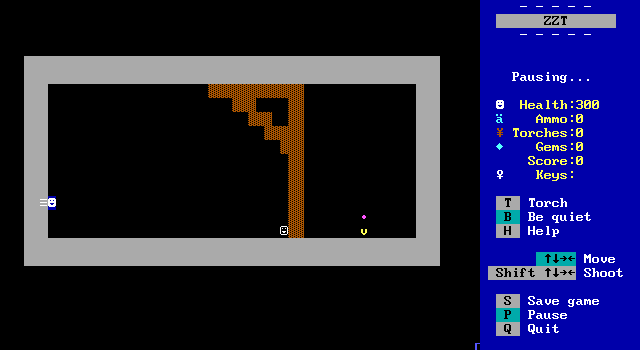

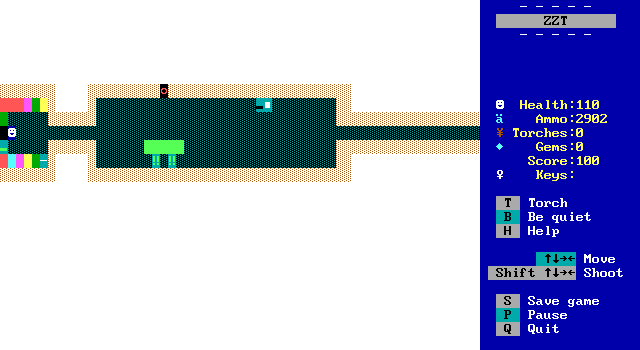

By late 1998, starting an adventure game off with a menu screen was pretty common. Credits, system explanations, and advertisements could all be crammed into a space separate from the diegetic experience of the game. Jack O’ Lantern does something a bit different. It starts you off in a closed-off cavern of sorts, with the game’s title hanging in the void and an authorial credit hanging out awkwardly below. At the top of the screen is a recreation of the title screen in miniature in a yellow frame.

Before you can really take all this in, though, a text box pops up giving you the exposition that sets the stage:

| | ELCOME to the the game JACK O'

|/\| LANTERN. You were on your way to

your friend's house for a Halloween

Party. Suddenly a bright light

flashed before your eyes. After you

cleared your eyes, you saw the house,

seconds ago full of life and music --

now "dead" silent. You peer in the

window and see nothing. It is

deserted. You feel an impulse to run

to the police station down the steep

hill. However, the sad and lonely

house beckons to you and you cannot

leave.

• • • • • • • • •

One wonders why this couldn’t have been better told through a story board or two. At the very least, it might have made more sense to put this on the first proper game board. The setup is frustratingly vague and generic, though the prose more or less set the stage for an adventure through a somber, eerie house.

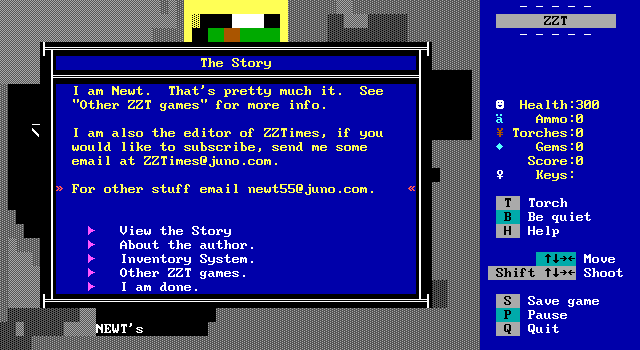

Other options in this initial dialogue menu are “About the author,” “Inventory System,” and “Other ZZT games.” “Inventory System” is actually required reading, which I assume is why I forced the player to choose “I am done” before exiting this menu (it will open itself again and again if you simply try to press escape).

I claim that the “inventory system is sort of based on Chronos’[s].” But I assure the player “He approves of to it’s okay,” in case you were worried about intellectual property theft (a hot topic for any ZZTer in the 90s). The inventory system is pretty simple, with an identical item placed on each board drawing up a list of inventory items on screen based on flags set when you interact with objects throughout the game. There’s a certain kind of object that can be interacted with through the menu, but we’ll get to that later. I recall that encountering inventory systems like those that Chronos used in his Chrono Wars series are what inspired me to attempt to bring my item-dependent text adventure to ZZT. It seems I sought Chronos’s permission to make the inventory system for my game patterned after his, though it also seems like I didn’t steal his wholesale. I can tell because the labels used in the ZZT-OOP for my inventory objects are the kind of random nonsense words (“erd,” “yay,” “vader,” “hola,” etc.) that have plagued my programming for over two decades now.

Anyway, the “About the author” section basically refers you to the “Other ZZT games” section, while getting in a plug for ZZTimes, an email newsletter I ran from a Juno account during 1998.

In the “Other ZZT Games” section, I advertise past games and upcoming games as well as, strangely, Jack O’ Lantern itself. Curiously, there’s a description of Zem that reads:

“In this mini-game to be packaged with Jack O’ Lantern and probably downloadable separately, you take on a unique interface to try to save a Lemming in a Creepers-style game.”

I’d forgotten that when I started it, I viewed Zem! as a kind of experimental minigame rather than a proper release--like, say, Jack O’ Lantern. I don’t recall actually packaging Zem! and this game together, and I think Zem! came out a month or two later, though it’s impossible to prove definitively now. I also apparently was working on an adventure game for Super ZZT called Four Silver Coins, though I have no memory of what this was supposed to be. The goal, as stated in the preview blurb, was to “collect the silver coins and destroy the evil,” so I am confident the world is a poorer place for this narrative masterpiece failing to come into being.

When you at last close the initial dialogue box, text appears at the bottom telling you to “Go in the painting to continue.” And that’s where the game begins.

The Adventure Begins

If there’s one thing that I think is of interest in these early boards, it’s the cohesion between the title screen, the splash board, and the first. The way the game is set up, you don’t see a full view of the mansion, so instead the game seeks to give you a sense of scale as you approach the place. That said, this first board is agonizingly sparse.The amount of space devoted to drawing the lawn makes the scale seem out of whack--a recurring problem with scale throughout the game, as we’ll see.

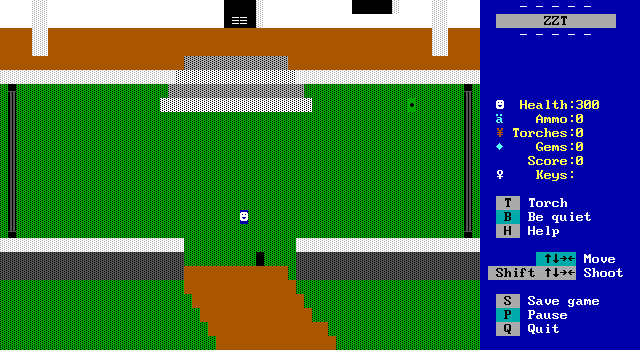

This is a ZZT adventure, so I’d imagine the first thing a player is going to do is try to touch everything that looks like an object. There is precisely one of those right here, a black dot near line walls on the right side. I’d imagine a player is going to touch that first. Touching the dot tells you both that it’s a rock and that having touched it triggers a mechanism that sends the gates underground.

Here’s where there’s a frustrating gap between what can be accomplished with a text adventure and the crude way I translated that plan into ZZT. A text adventure description of the house might’ve told you about the presumably metal gates that section off the walled front lawn, the pillars on the front porch, the rock, and maybe a few rogue elements. Inspecting the rock may have done nothing. It would only have been when telling the text parser that you want to “hit” the rock that it would trigger the mechanism. ZZT has a very limited number of ways to interact with objects. “Touching” stands in for any verb that might’ve been applied for a text parser. There are ways to design around this limitation, but I either didn’t care about those, or didn't want to exert the effort.

With the gate descended, you can head to the right (the left is still blocked off). The lawn continues and against the far wall, you see a red item and an odd-looking piece of wall. Touching the red object lets you know that you’ve taken “the red potion,” which will now show up as “Red Fluid” in your inventory menu. You can click on the hypertext to examine it further, but all it tells you is “It is a red fluid. It bubbles.” The odd spot on the wall to the south of the potion gives you a necessary hint for what this might all be about--though, curiously, this gives you the option to read or not read it when you touch it.

• • • • • • • • •

It says:

-=-=-=-=-=-

This crude poem presents the solution to the central puzzle for the whole game. In a sense, this isn’t a bad way to start off the game, in hindsight. The primary way you’re going to interact with the game is by picking up items and touching things in search of clues, and the very first clue you receive is going to be one you need to hold in mind for a long time. It would be more compelling, though, if the puzzles that followed were structured more interestingly.

For now, there’s nothing left to do but go back one screen and enter the mansion.

The Mansion

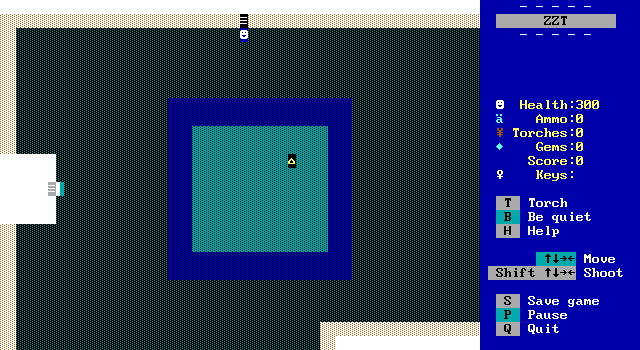

It’s quiet in here, as advertised. It’s also exceedingly roomy. Touching the object next to the passage on the left reveals that “It’s a door,” which isn’t terribly helpful. On top of the rug is a “Candy Bag.” When you touch it, the game makes a lot of decisions for you:

So, yay, you get a twist tie in your inventory.

You’re evidently out of things to do in this room, so you have one of two ways to go. Let’s go east first.

This kitchen is really weird looking! The game’s scale issues are evident here, as I awkwardly mapped the floorplan of the adventure game to a ZZT board grid. The appliances look somewhat jarring and out of place as does the “pantry,” in no small part because of their rather careless appearance using only stock ZZT colors and not the Super Tool Kit-inflected visuals that populate most of the game. There is an exception, of course, and that’s the dark red space alongside the bright solids on the pantry, er, shelf. In my original plans for the game, this was supposed to be a hidden passage behind the pantry, accessed by moving some old box or something like that. Instead, it draws a lot of attention to itself and makes you wonder how the hell your friend hasn’t wandered back here. You just might be tempted to think it’s a passage. And it is! What does it lead to?

It’s an awkward miniboss battle (with the ever-present inventory object not even disguised in the lower right corner)! The game tells you “You find yourself faced with a skeleton. He carries a sword and disappears now and then. He screams and attacks you.” The skeleton, I suppose we can presume, isn’t always here and is an effect of whatever dark magic that has gripped the house. The orb in the room, though, is anyone’s guess.

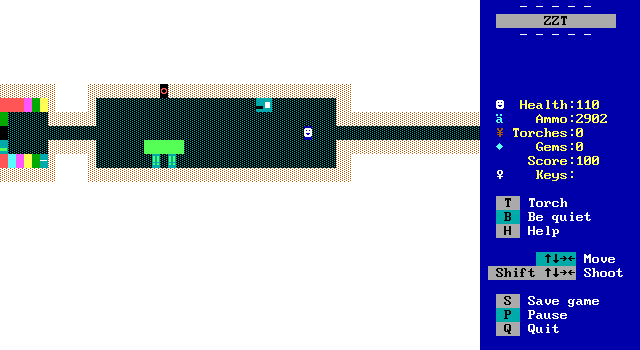

Anyway, there are a limited number of ways to do combat in ZZT and this isn’t an especially creative one, so the game gives you 3000 units of ammo and makes you bullet spam a skeleton enemy that bullet spams you in return. The appearance here seems to be a side-view of a room, but both you and the skeleton can fly around freely. The skeleton screams things like “ARGH” and “Grrrr…” when you successfully hit it. This is the only board in the entire game where your 300 health has any use. When you defeat the skeleton (which gives you the game’s only points--100 of them) after an inordinately large number of successful shots, the brown support beam fades away and you can get access to what was behind it.

I was surprised to find the sword-wielding skeleton was indeed part of my original text adventure plans, though I have no idea you would’ve fought it in that version. It would hit you for two health points, though.

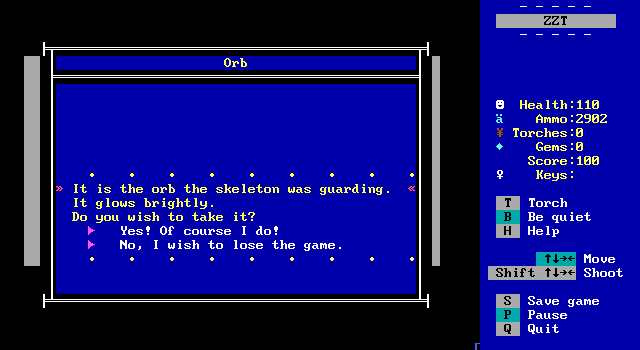

Touching the yellow object lets you know it’s an orb holder. Touching the purple object above it lets you take the glowing orb itself.

My writing couldn’t resist the awkward, strained, desperately ironic self-awareness of my age (both in terms of how old I was and what year it was, I mean--this was the height of applying a Mystery Science Theater-derived glib mockery to everything), I’m afraid. If Jack O’ Lantern was aiming for a consistently eerie, lonely tone, between the weird skeleton shootout and the dripping smarm here, I think this board might have just squandered it.

Back in the kitchen, we can touch the stove to find out that it’s hot to the touch, though that has nothing to do with anything, apparently. Touching the line object in front of the southern passage gives the cryptic message “It is a rusty wire to the dumbwaiter.” I believe this should be something like “This is a dumbwaiter, but when you attempt to operate it, its rusty wires refuse to move.” Your way blocked, there’s nothing left to do here for the moment.

Going back to the room south of the entrance, we find a technique that probably should’ve been used more lavishly in this game: multiple rooms compressed into a single board.

You can take the object by the fireplace only if you profess your love of the flame. Otherwise, the game low-key shames you for being a momma-loving baby, apparently.

You can enter the bedroom. You only find out whose room it is--your friend, whose name is Ted, apparently--by touching the nightstand. Otherwise, the room is mostly a vehicle for references to ZZT.

No one has actually said anything about Ted’s tastes, but okay. Nothing like a little bit of smug, satisfied self-referentiality.

You can open the closet door and enter it. The game lets you know that Ted is much neater than you, the sole bit of characterization the otherwise anonymous player character gets in this game.

When you enter the room off the board and across the hall, a message tells you it’s Ted’s sister Jennifer’s room. That’s nice. Jennifer has a fishbowl, though it’s unclear if there’s a fish in it or if aquatic pets disappeared along with the occupants of the house before you got here. There’s nothing to do in here otherwise. Jennifer doesn’t even have a closet. There is, however, an extraordinarily large amount of blinding white space and this board is an eyesore.

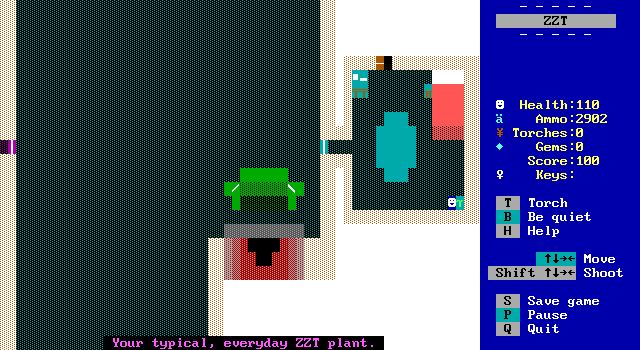

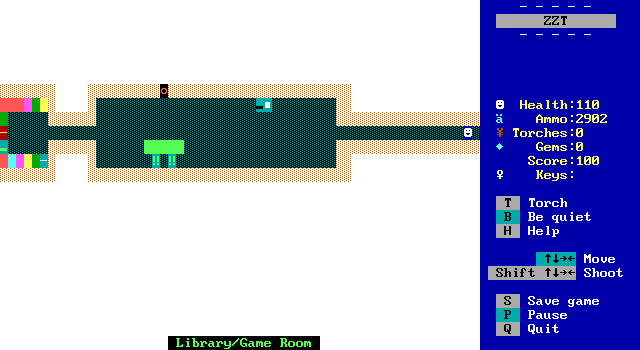

Continuing south from the previous room, there’s a bathroom with a “ZZT standard toilet” you can flush and a sink. By 1998, ZZT toilets were known as a kind of community meme and a ZZT tradition, and I relished participating in it. Entering the room opposite takes you to the game room and library.

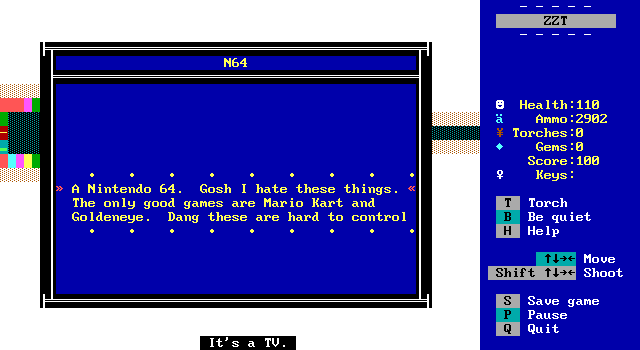

While Ted may have great taste in computer games, his taste in consoles is dubious by this game’s standards, apparently. In the middle of the game room is a line and a box representing a Nintendo 64 and a television.

Touching the N64 gets you access to a rant with my rather severe opinions about 3D gaming in the year 1998. This was, of course, intensely embarrassing. Even more embarrassing is that this rant is, in fact, the entire point of the game room portion of this board, since the other objects only identify themselves.

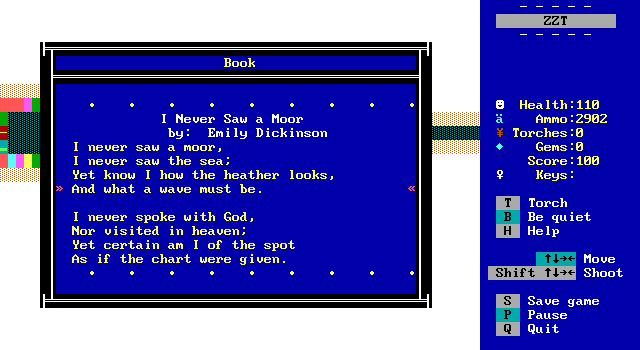

However, the library has a few things to consider. A few of the books (the ones with STK-derived colors and markings on their bindings) can be interacted with.

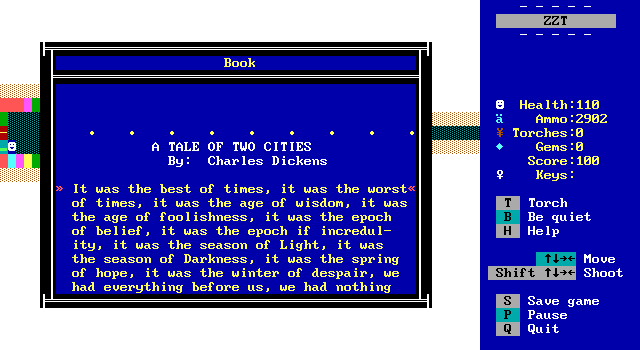

The library is where I put a weird amount of effort into verisimilitude. One book contains an entire Emily Dickinson poem and another the first paragraph from A Tale of Two Cities, both of which were assigned reading for my ninth grade literature class.

When you tell the third book you want to read it, though, the object simply dies, opening up an entrance to the next board.

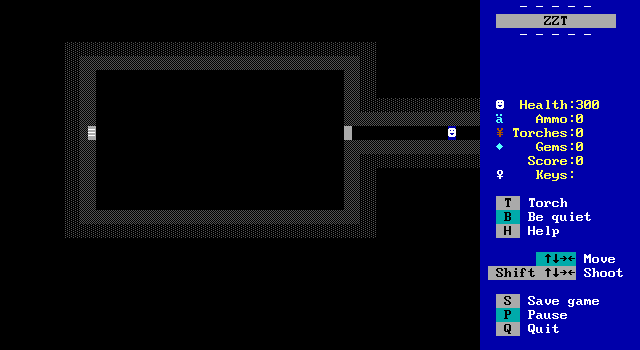

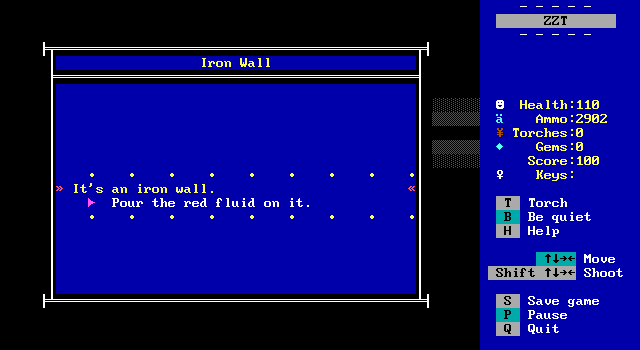

Now we’re in a sparse, dark gray room with a single light gray wall. While the previous board was too loud and noisy with its bright white voids, the darkness of this room does feel like a nice, gloomy contrast. Touching the wall gives you the option to pour whatever fluid(s) you might have in your inventory onto it. That might seem to be a weird thing to do with an iron wall, but that’s where we’re at. Right now we only have the red fluid. Attempting to pour it on the wall does nothing and mercifully leaves the red fluid in your inventory.

It is painful how long it takes to traverse these nearly-empty rooms. I wonder if I’d thought the incredible amount of negative space in each room justified my calling the house a mansion when in fact it’s not really that large.

Back to the last junction, we’ll take the passage at the end of the hall.