One of the fun things about documenting these ZZT games, is finally going back and getting some closure on games I played when I was young, but was unable to actually complete. It's been really something playing through the complete works of Alexis Janson and getting through lengthy games and series like Fred! Episode 2 and Chrono Wars. Many of these games have had reputations as being classics, which was half the reason I'd checked them out in the past to begin with. Revisiting these games now with a far sharper eye for seeing what works and what doesn't, it's always compelling to discover whether they live up to their hype or not. Even when a game turns out to not hit as hard as it did to high school aged kids at the turn of the century, it's hard to truly say a game doesn't deserve it. ZZT has always been about compromising your vision, finding a way to transplant something from your imagination to a shareable file that anyone can play. The limits often lead to authors painting themselves into a corner, and one suspects they're just as aware of the flaws as anyone else.

It's hard not to have sympathy, and good intentions were pretty clearly enough when your audience consists of fellow ZZTers who would have made the same mistakes and been just as incapable of finding ways to somehow bend ZZT into making games too complex for the poor little program. So when good enough is as good as its gets, games that are good enough get to be elevated to high status. Darkseekr doesn't have this reputation. Anthony Testa was prolific at the time, and a number of his other worlds still hold up strong even now, but not Darkseekr. This is one I played a bunch as a kid and was very inspired by with its unique form of dungeon crawling that made it unique from Testa's more traditional dungeon crawls that rely on active spelunking rather than patient, plodding exploration. I was hoping with this one that a game I loved, but struggled with, would just be a case of being too young to succeed, or at least yet another case of a game where a little extra health and ammo via the cheat prompt would be enough to get some mileage at it.

Folks, what I got from Darkseekr is the realization that a game I loved is a train wreck, and worst of all, one where the tiniest effort being put into prevention would have not just kept the train on its tracks, but probably made for one of the smoothest and most luxurious rides around. A near-classic that instead chose to be nearly-functional.

I Gave My Blood To Dark Entities And All I Got Was This Lousy Kidnapping

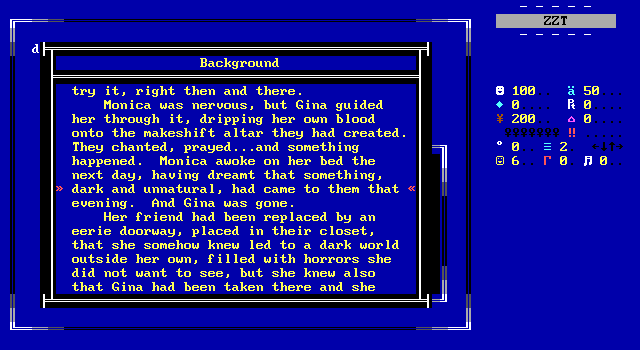

Darkseekr includes an in-game backstory you can read before jumping in. It tells the story of two teen-aged girls, Gina and Monica. Gina is a bit of a rebel, trying to break free of her overprotective parents. Monica is the introverted computer nerd. (She has a laptop.) Both ladies became friends over their shared love of the occult, and it's that interest that leads to trouble.

The two rent a cabin in the woods for a weekend, planning to perform a ritual to summon a spirit from "the other side". This is no Ouija board seance. Blood is spilled on their makeshift altar with the appropriate chant and... something happens. Monica awakens in bed the next morning with no memory of the events of last night, just a unpleasant feeling that it wasn't anything good. Her fears are confirmed when she first discovers that Gina is nowhere to be found. A second discovery of a portal in the closet leading to a dark world convinces her that Gina has been taken, and her life is surely in danger.

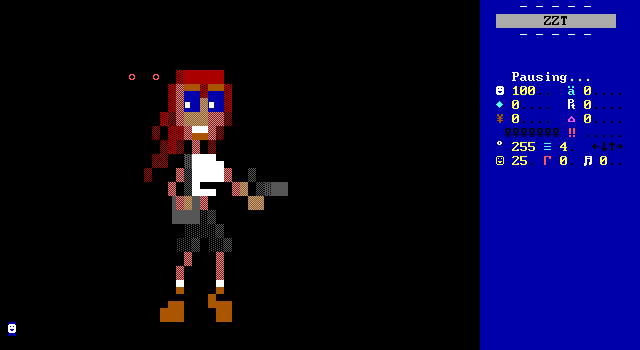

Monica dresses for combat in a classic Lara Croft-era 90s outfit, grabs Gina's handgun and enters the portal not knowing what waits her on the other side...

In order to reach Gina, Monica needs to fight her way through six floors of a demonic temple filled with all kinds of terrifying monsters and ran by an order of manic religious figures that use the temple for both ritual sacrifice and unholy experiments in creating life. Gina's gun is Monica's only companion, but if she can find some of the temple's treasures and pawn them off to merchants she may stand at a chance at finding her friend and making it back home alive.

The introduction sets the scene nicely. Darkseekr strives to be a creepy game of player versus demons as they make their way through a temple filled with gruesome scenes. Yet the structure of the game makes it difficult to do compared to Testa's other dungeon crawlers, or most any ZZT game really.

Crawling

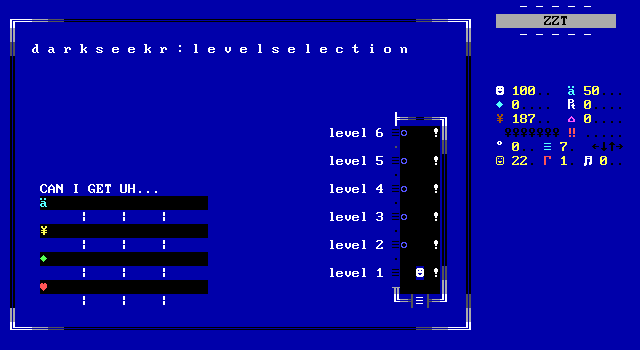

Unlike a traditional ZZT dungeon crawler, Darkseekr uses a series of engines to handle everything in the game.

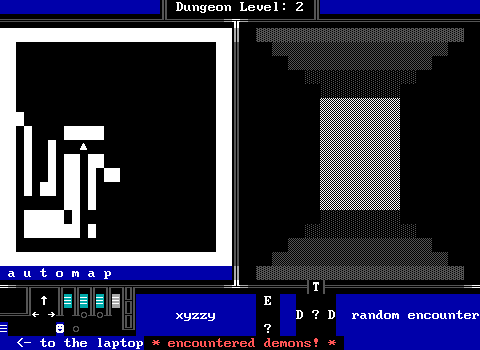

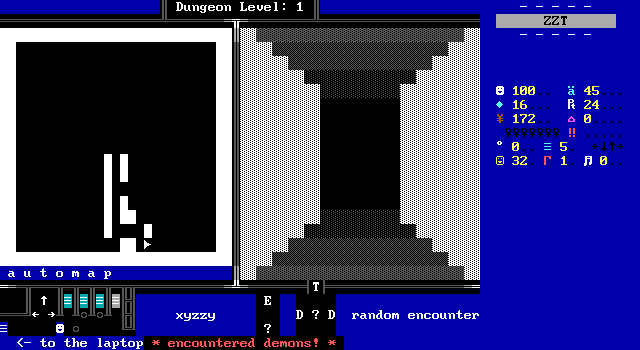

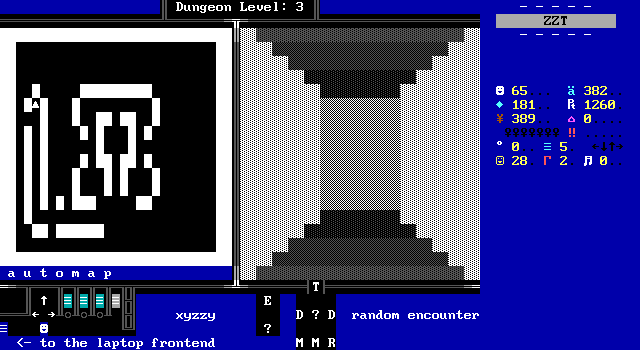

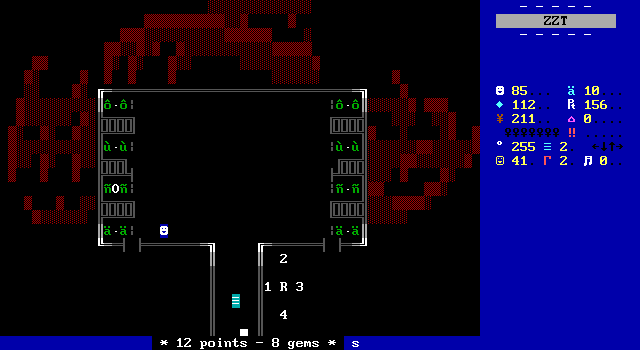

The crawling of Darkseekr takes place on a dedicated map screen that makes use of an engine similar to the "first person ZZT" engine demonstrated by JMStuckman's Maze 3D from 1996. Players are tucked in a corner with some arrows that move Monica forward or rotate her facing. After a move is processed, the marker on the map checks which directions its blocked in, placing walls on the automap and adjusting the visibility of some invisibles on the first person view to give players a sense of what Monica is seeing.

After each input, the game rolls to see if players get a random encounter, and then what kind of encounter it is. Your exploration is regularly interrupted by discoveries good and bad, and you better get used to it. The encounter rate is quite high making exploring even a single floor completely a rather daunting task, even before the mechanic of torchlight is considered.

Interacting with the map at all consumes a single torch for every step you take, rotating in place included. Resource management is the core mechanic of the game. If you run out of torches, the game is over. Though if things get that bad, there's a mercy system which allows you to trade fifty health for one hundred torches. It's an offer you can't refuse.

Odds are though that if your torches ever get this low, your health isn't any better, but at least Testa is thinking about you.

This engine is certainly clever. A number of games over the years have used it as a way to mix up exploring a maze, and be able to claim its impressive 3D work thanks to the first person view. Players meanwhile have without fail looked at that 3D view had their moment of recognizing how cool it was, and then proceeded to navigate entirely by the map instead. Testa's programming is (at least in the beginning) in a good place, but nothing in the game was really pushing boundaries even then. Darkseekr combines a few ideas to create a memorable delve into the darkness, opting to wow players with solid design principles that create an engaging experience.

Navigating via map is inevitable as the first person perspective only shows walls immediately surrounding the player, and the lack of colors accessible in ZZT-OOP makes it impossible to add any kind of texturing or markings to differentiate one T-shaped intersection from any other. Later ZZT games like Angelis Finale would have players adjust the game speed and use the extra processing time to have the marker scout out more of is surroundings, providing a slightly larger field of vision. Even here though, the automap remains king.

But Darkseekr is closer to Town on the timeline of ZZT releases that it is to Angelis, and the idea of increasing ZZT's speed deliberately just wasn't a thing back then. The "first person" feature is true technically, and the term should be treated as seriously as the idea that Canid Productions is a real company that produced Darkseekr in a professional capacity.

While it's not what an outsider expects when they hear the term, to the ZZTers all playing pretend with one another, it remains an impressive piece of tech. The limitations are after all ZZT's fault rather than Testa's. Surely Testa would have wanted a larger field of view, but his hands were tied. ZZT doesn't do that, so this is a 3D as it was in 1996 and as 3D as it remained for nearly another decade.

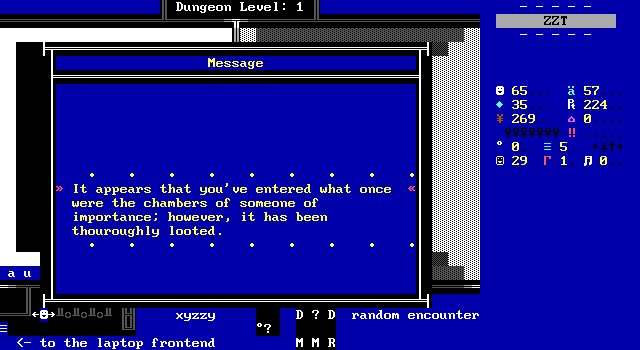

With nothing but white walls to look at throughout the entire game, Testa has to find another way to make his temple come off as anything more than a 3D maze. His solution is to place special landmarks unique to each floor. Upon reaching one of these spaces, a text window opens which describes a richer scene than the labyrinth can provide on its own. Afterwards, they're drawn over with walls like any other tile making them one time events and not annoying popping up every time you pass the point.

The messages cover a wide range of events. Some are as simple as discovering a pile of bones. Others provide special one-time bonuses, like wandering into an acolyte's chambers and stealing their gems. In at least one instance, the messages interact with one another. A weird old man searching for his bucket dejectedly wanders off, but it's possible to find the bucket elsewhere and decide to take it. Doing so nets you some extra money as a reward for helping out.

Due to the one time appearance of these messages, it can feel a bit contrived. Monica doesn't have any reason to want to take a bucket prior to meeting the old man, but if she has met him, then he's already long gone and the bucket becomes pointless.

You'll find typical dungeon features in these events as well. Look out for fountains of tasty water, fountains of less tasty blood, dismembered corpses and so forth. There's the occasional hint that others have been here before you when Monica finds a dismantled uzi and salvages some nearby ammunition. The strange world players find themselves in doesn't get explored in detail. Whose temple this is, where they are, what has happened to those who have found themselves here before are all questions that Testa has no real intention of answering.

The most you get is at the end of the game when the priest that has taken Gina and plans to sacrifice her provides his motivation of binding her soul here so that he may free his to travel back to the much nicer Earth.

It's not just at the end where players can run into the temple's denizens. Special events also cover meeting up with some dark priests which in turn tells the game to force an encounter.

The encounter function in this regard is kind of clever in how it gracefully degrades in these moments. Nothing stops the game from rolling a normal encounter at the same time as these special events, however the door opening to one encounter passage blocks those to the right of it. The same flag is used to track when you're in any kind of encounter, and so if two doors are open, you're stuck going in the leftmost one and having the rest close off. The game prioritizes enemies over treasure over merchants, preventing players from ever getting a lucky break that lets them skip a fight.

The encounter rate is really high. Every time Monica moves (or rotates) the game has a 1/4 chance of generating an encounter, which is then broken up into which type of encounter it is. Demons are a 50% chance, with merchants and treasure each having a 25% chance. Due to all the passages being manually entered, a lot of time is spent not moving through the dungeon, but just just walking from the navigational controls to the encounter and back.

Another, even later Commodore game came up with a solution to this constantly reoccurring downtime. Psychic Solar War Adventure checks when the player leaves a location and return to the world map, with an object recognizing when the player is aligned with it that then pushes them back to the main controls by using #PUT with some boulders to move the player multiple spaces instantly. I really found myself missing such a quality of life feature here. Again, it's a level of polish you shouldn't be expecting in a 90s ZZT game, where the walk is part of the cost of the dungeon crawling engine rather than being another problem to solve within the engine itself.

With the simple task of moving being handled by an engine, it's the game's combat that ends up relying most on what ZZT provides without code. As Monica is packing heat combat the vanilla type, with players running around a board and shooting at enemies. Traditional action in an otherwise very non-traditional game.

Demons get to be shot just as if they were lions or ruffians or any of the more standard adversaries for players to face off against. With the player element not actually wandering the halls of the temple, the usual technique of sprinkling enemies along the way as obstacles can't be done here.

Instead, when an encounter with demons is rolled, players head to a dedicated combat board which handles all the combat for a given floor. A randomly fired bullet chooses from four sets of demons to fight, with two enemies being released and the passage out being closed off until the player defeats both of them. Players are rewarded not for finishing the fight, but for each monster defeated. The difference doesn't matter early on, when enemies only drop gems and provide points, but later foes will drop ammo as well, and getting extra ammo during each fight is greatly appreciated.

This re-usable fight scene is admirable in some ways, yet noticeably lacking in others. Repeatable combat in general is not something ZZT is very good at, and at the time of its release, this system is something ZZTers would have taken note of. Even with a small pool of possible fights, there's a sense of variety here. It's not long before you'll see which doors open at the start of the fight and either breathe a sigh of relief or grumble to yourself.

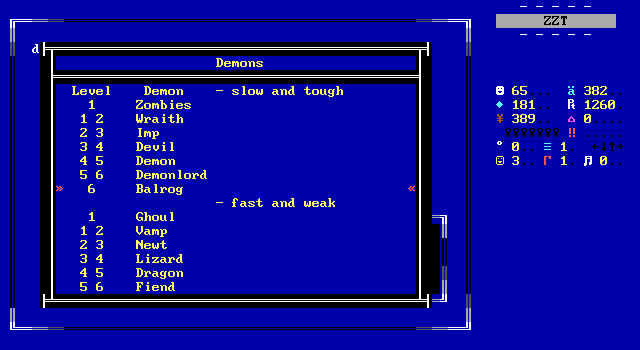

Testa includes a bestiary in the menus that divides his enemies up into "slow and tough" and "fast and weak", listing their names and which levels they can be found on. I'm always a big fan of knowing exactly what you're up against, and appreciate having better ways to refer to enemies than "an e with umlauts". Zombies, wraiths, demonlords, ghouls, newts, dragons, and even balrogs make an appearance in Darkseekr, at least according to the reference material.

Sadly, the unique names of everything are never brought up when you fight. You simply encounter demons with generic "The demon attacks" messages when you're struck. In Defender of Castle Sin, the game's updated release transforms lines like these into specific nouns and it really makes enemies more memorable and less like an arrangement of HP/damage/speed stats. Darkseekr would benefit from such a thing, as the engine gives Testa very little opportunities to craft a narrative.

Monsters can't be built up as big scary threats when they all duplicate in the same way as any other battle. I could only identify a single enemy by name after playing through game, and even that is because I wanted to double check their code early on to see if they really were as much of a menace as they appeared to be. (They were. Fuck newts.)

Combat is also lacking in terms of enemy variety. While there are more than a dozen demons to do battle with, every single one of them is dark green. Nearly every character used is an accented letter as well, save for a few ligatures. These characters feel very arbitrary. Thinking about it, the characters used here are ones that are usually seen as ripe for replacement with custom character sets. If Testa had wanted to to really give the enemies an identity, this would be the way to go.

With no nouns ever appearing to tell players what they're fighting, every enemy feels too similar. The code situation makes it even worse as every enemy also follows the same basic loop, just with adjustments to cycle and damage as needed.

The shared engines also lead to a lack of variety in the arenas in which you fight. It's the same rectangle with a narrow hall attached every time. An empty arena provides no cover other than the passage you enter the board in and does not make for exciting fights, especially when fighting the same enemy for the fifth time. There's no meaningful variety here other than slow or fast monsters.

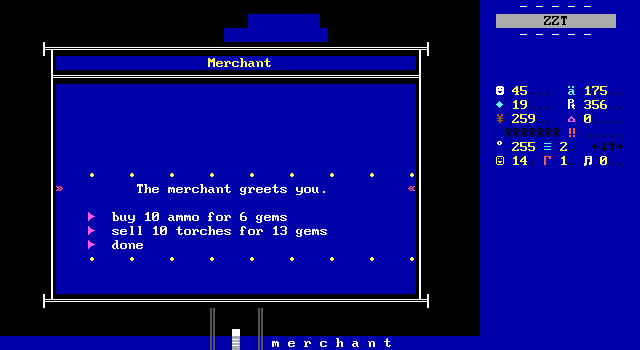

Resource management comes into play here as well. Monica's only offense is Gina's gun which makes ammo management essential. Enemies are annoyingly sturdy, often taking five or more shots to kill. Due to the randomness of what supplies players find and when they'll find them, running out of ammo is an all too real possibility. This is especially true early on when players lack much of a buffer of spending money making it possible to run into merchants that would be all too happy to sell you some bullets, only to tell you to come back when you're a little mmmm... richer.

A dagger would do wonders here. Even if it was meant only to be used in the most dire of situations. It's annoying to miss your shots and run out of ammo during a fight, but it's even more so to have so little ammo, roll a fight, and not even have to enter the room to know that it's game over already. It's even stranger considering the mercy system for torches. At the very least, extending it to ammo as well could prevent a lot of game overs that are inevitable if your ammo is too low for the fight.

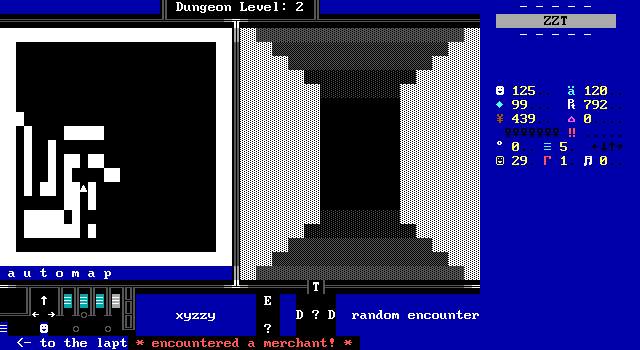

Treasure and Merchants are the other encounter types, and ones that you have to roll if you're going to do anything other than run out of supplies. These take on a much more passive form, to the point where they could have been handled entirely from the map screen. This would have meant losing the awesome art though, so the walking from passage to passage is worth it honestly.

Both of these encounters have an object moving in random horizontal directions that will always be blocking a single object above it. Touching the main object to see what you've found has those objects figure out which is blocked, and then display the appropriate merchant/treasure according. Seven options can be rolled, with the specifics of each encounter changing on every floor.

Treasure is treasure. Free gems, torches, or ammo in varying amounts, with a chance of a trapped chest instead to make the encounter not be a guaranteed positive. Players do have the option to not open chests, but unless a trap will kill you, it's not worth passing up the rewards. Even if you are critically injured, it's still worth playing the odds rather than skipping out on a lot of other supplies until healing can be acquired elsewhere.

The merchants are straightforward as well, however they have a lot more nuance to them. Each of the game's random merchants offers different items, in different quantities at different costs. This lends itself to strategic purchasing where a player getting low on torches might pass up the opportunity to buy some if the asking price is too high. At the same time, if players are foregoing a purchase, they run the risk of having to take an even worse deal if their supply gets dangerously low. The randomness of the game makes everything a balancing act where the player needs to figure out what level of risk they're comfortable taking. The more cash players save between purchases, the more they can take advantage of a good deal should one show up.

Adding to the logistics, a few merchants also let you sell items back to them. The amount of money received combined with how hard supplies are to come by make this a mechanic that rarely feels worth taking advantage of. Selling items seems like another move designed only for desperate players that can let them restock on an item they're dangerously low on knowing that it won't be long after that they're just as desperate for the item they opted to sell.

This loop of exploring a level as the player repeatedly gets into the three kinds of encounters makes up the entire game. Things are only broken up by the occasional unique message, though these are very easy to miss. Without any real landmarks, exploration is just picking directions at random, hoping to stumble across the entrance to the next level. While the game's menus get into the spaces you're exploring and what horrible things have happened there, it doesn't translate to the gameplay. Whether you're in the sewers, the inner sanctum, or the laboratory, nothing sets these spaces apart from one another. You'll see everything there really is to see in Darkseekr on the first floor, but that's enough to realize that the simple formula can be a highly effective one.

Testa's design is brilliant in its simplicity. The game sets itself apart from others, even Testa's many other dungeon crawls, by making everything a resource. Each step you take in the dungeon means one less torch. Enemy encounters drain ammo, only providing gems which are useless until you can convert them into something useful at a merchant. Health is the hardest resource to come by, only "reliably" accessible at a specific merchant. Each roll of the dice narrows the possibilities and recalibrates what you're hoping for. Obviously it won't be treasure every time, but you'll be praying for good deals or for the healer to show up. Even in encounters, the four possible fights mean focusing on the set of doors you hope are about to open, or perhaps the ones you really want to see stay shut.

One other quirk of the way the game is arranged is that players are welcome to revisit any previous levels and continue exploring them. The game scales it encounters, so treasure chests found on floor four will have greater rewards than the first game. This applies to demons as well with weaker foes on the upper levels. In theory, if you're in a bind, you can try retreating to an upper level where you can get through more battles with less health and ammo than on your current floor. It's hard to say if this is advisable as torch drain is constant, and the torches you'll find for sale or in chests early on are going to be in smaller quantities as well making you more likely to run out there than later on in the game.

I suppose if you really wanted to go for broke, you can encounter a merchant on the floor you're on, not actually enter the passage, and then go back to a previous floor to safely farm money. You'd also be able to put off an encounter with demons you don't want to enter this way. The game would slow down immensely doing this, so I wouldn't advise it. You're better offer just savescumming to avoid demons if you really can't fight them due to a lack of health or ammo. It's very much possible to savescum treasure and merchants until you get the one you want, though the way those rooms randomize their encounter make it harder to get a specific roll.