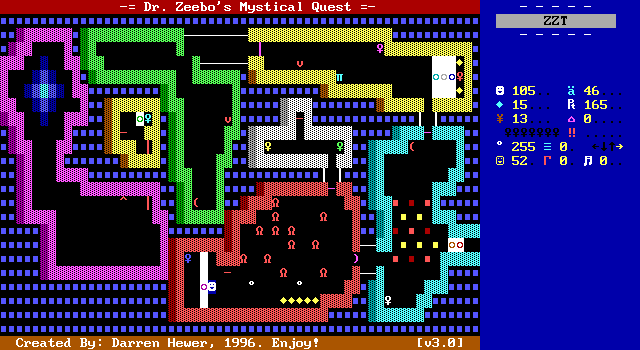

This month's patron-picked subject for a Closer Look is Dr. Zeebo's Mystic Quest. A game with a top-tier name in which players seek out the mystical Dr. Zeebo to learn the secret of the meaning of life. This particular release is the final one which makes use of Super Tool Kit graphics to create a vibrant and colorful quest. On their journey, players travel through a series of rooms covering a wide range of obstacles to fight your way through. There's plenty of action, as well as a few puzzles, and the occasional maze, or just whatever the author can come up with. It's a bit like one of Sweeney's original worlds, without the purple keys or open-ended layout.

At the time of the original 1995 release, this style of game was beginning to fall out of fashion. ZZTers had plenty of other games to take inspiration from well beyond ZZT's official worlds. 1995 brought us some longstanding classics, ranging from simple story-focused adventures like Legend of Brandonia or the first of the Link's Adventure series, to more complex games that pushed what could be done with storytelling and player choice as seen in Warlock Domain. ZZTers had come to realize that they could use a story to give purpose to the spaces players would run and gun their way through, finding ways to turn a room full of lions from an obstacle on the way to the next purple key into a tribe of trolls that control the woods. The more abstract piecemeal boards were giving way to interconnected worlds. Authors were promoting their games not with promises of hair-pullingly difficult puzzles and frantic action, but rather detailed worlds for players to explore with unique characters, places, and conflicts. ZZT was evolving from a text mode arcade game to a medium capable of playing with players' emotions.

But the older style never truly went away. Because it is, after all, a good one. Making ZZT do what ZZT was designed for might not drop anyone's jaws, yet it sure could keep players entertained for an hour or so. The numerous creatures and puzzle pieces, with just a hint of scripting to enhance the experience is really all you need. Any programming was to create the kind of things you might imagine would be available out of the box in a hypothetical ZZT v4.0 rather than to prove ZZT to be more capable than it appeared.

Dr. Zeebo is such a game. It's a series of boards each of which offers their own idea on how to challenge players that could pretty easily be played in any order, never seeing a need to try and explain itself. Instead, players are sent on a journey through anything author Darren Hewer could come up with. It's a real kitchen-sink of a game, but don't let that fool you into thinking that it's a haphazardly constructed one. There's an unmistakable spark of enthusiasm that runs the entire duration of the game.

Hewer's broad range of ideas treat players to all sorts of fun surprises, with rarely a dull moment. (There are dull moments, the game does fall back on mazes a bit much.) For fans of old-school ZZT, Dr. Zeebo's Mystic Quest is a shining example of the fact that while the format's popularity may wane, it will never truly die.

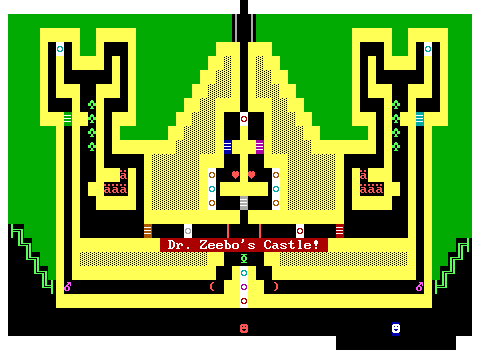

Before even beginning to get to the game itself, it's worth pointing out that it's only this final release of the game that finally sees fit to have a title screen. Prior to this, the game was a title screen starter, going for the absolute minimum time from loading the world to playing it.

Now, the game fits in more what everyone would expect. A nice little logo, a name for the creator, a little drum beat, and of course flashing text to explain to players what they're about to get themselves into.

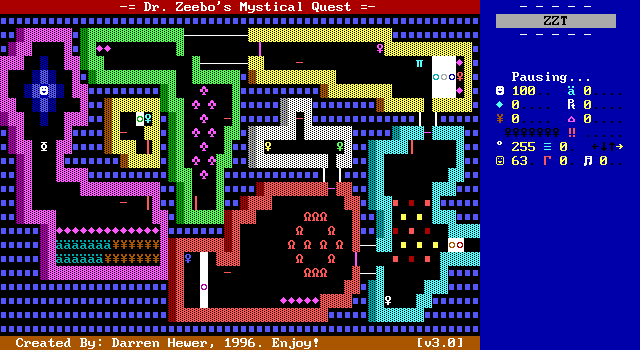

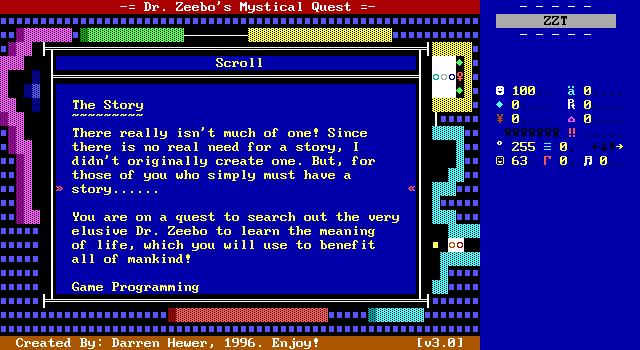

Despite the new title screen, Hewer's former title screen still carries signs of its former role, providing the repeating the title screen's information along its border, and sticking a nigh-indistinguishable copy of the story into an opening scroll.

That scroll is actually a great artifact for the game, going into details on how it was first made in 1994 and went unreleased, with the occasional return to it to touch up the game and make it more presentable.

There's even a declaration of Hewer's goals when making the game. He wants it to be both enjoyable and unique. These two things, we'll soon see, are something the game very much excels at.

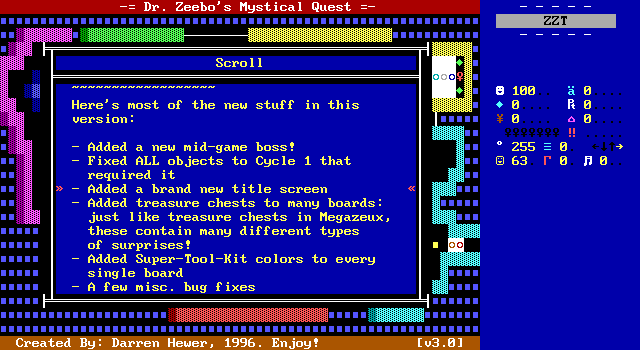

It even features a detailed changelog documenting a removed board, speeding up some objects to run at cycle one, new bosses, bug fixes, the addition of STK...

But I think one of the big ones is replacing a lot of items that players would previously pick up in large patches with treasure chests inspired by the ones in MegaZeux instead. These are a lovely addition that looking at previous releases definitely save player time. They also mean that what you get goes from being known to a fun little surprise. You don't really think about the contents being hidden until you first find yourself running low on ammo and getting that sense of relief when you pop one open and get exactly what you needed.

That's not to say that every pickup is now a chest. Hewer's changes add a little bit of variety that make Zeebo stand out. There's no blueprint the game ever follows perfectly. Every rule can be broken if it looks like it would make for a better experience at the moment.

For the introduction, players grab their supplies and are immediately presented with a choice of which transporter to take. Zeebo has a good number of boards like this that break up a board into individual sections connected by transporters. These usually rely on another staple of the game, the use of keys and doors to force players to engage with every section, and as a goal to eventually let them proceed to the next screen.

Players will quickly discover that a number of transports are one-way, making unraveling the entire space effectively to reach the next key/door needed a real process. It's all in good fun as you're unable to get stuck and the delays added if you overlook an exit feel shorter than if you stopped and studied the entire route before making any moves. The penalties are so light that players can get over it right away while still feeling pleased when your path is undeterred.

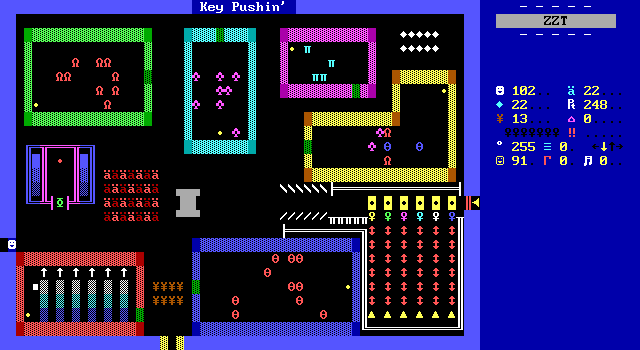

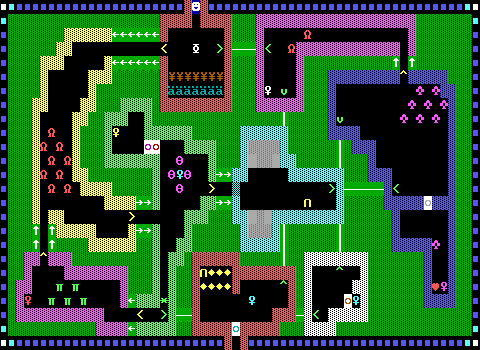

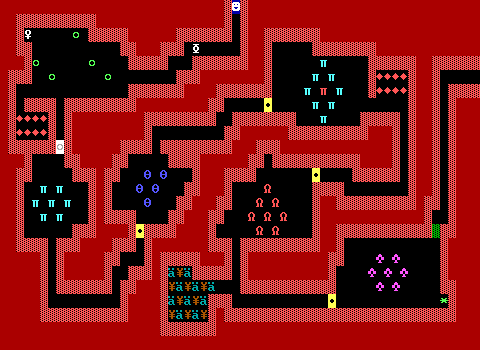

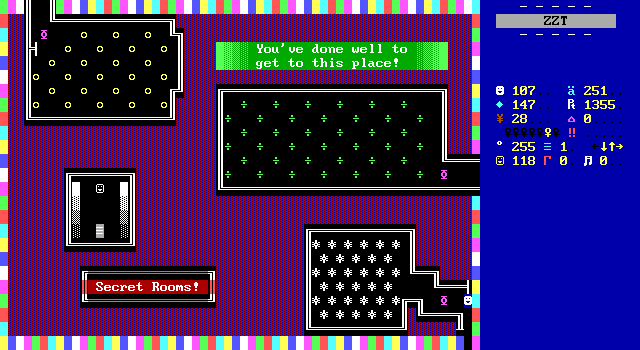

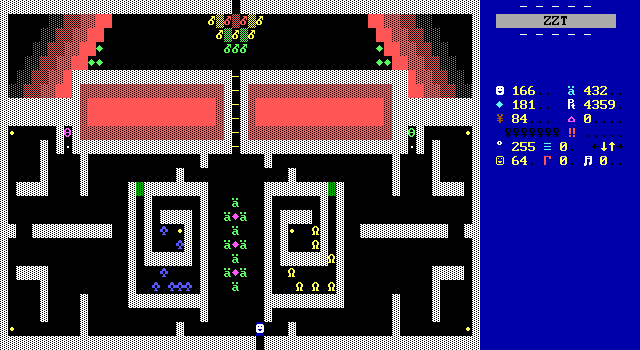

The board is followed by a real sensory overload of a board. It makes use of all the colors of the ZZT rainbow!

This time, players are much more free to choose where they want to go first. While the goal is again to grab a near full set of keys, each of the rooms here has a button instead. What would otherwise by a vacant part of the board is instead a whimsical contraption to dispense the keys when they're all ready to be grabbed.

Thanks to the buttons, the key collecting is done all at once, with a satisfying sound of jingle-over-jingle as they're all rapidly collected. It's a dopamine hit compared to grabbing one key per chamber.

Any decision paralysis leads to another tiny penalty. The red chamber's spinning guns slowly chip away at columns of breakable walls that can serve as shields. If you're attentive and notice quickly enough, you can get some refuge from the guns when you cross as there may be breakables remaining. If not, no big deal. Hewer seems well aware that he gets no benefit from punishing players for not thinking like he does. For an open-ended board like this to work, having a correct order would defeat the purpose.

The upper chambers offer no surprises. Pick a built-in to shoot, and go for it. The lower room with the centipede heads, features a tiny number of invisible walls, again, just enough to surprise the player without having so many as to make navigating the space unfun. It's just two columns at the sides, and four additional walls forming a diamond in the middle.

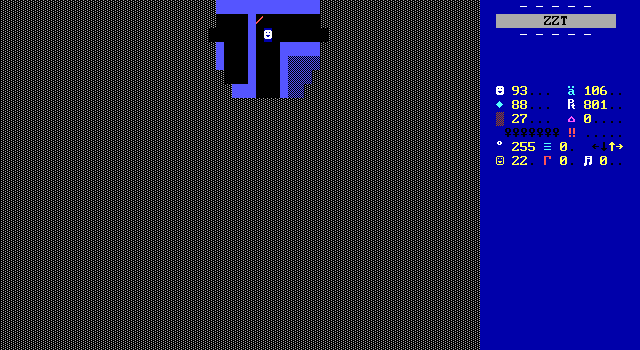

The strong start is quickly followed by my pet peeve of a maze with no danger other than the unrealistic fail state of running out of torches. This dark maze is the first of a few, but despite being so early into this adventure, this isn't a sign of Hewer lacking in the ideas department.

Despite the simplicity Hewer still has plenty of signs of smart thinking even when the concept itself is flawed (imo at least). For one, I found myself admiring the use the half blocks around the doors. It's a small touch that makes the board more interesting to look at, as if the doors themselves are an addition that wasn't part of the original maze.

The maze has a few other attributes that make it not as bad as countless others. There aren't actually a lot of branches to take, and most of them terminate pretty quickly. Every dead end also throws players a bone by being filled with collectibles, which also serve as the introduction to the treasure chests. Will it be ammo? Will it be health? Will it be more gems? Players will want to explore these corridors to find out.

Lastly, a lever on the final path out is interpreted by the unnamed protagonist as perhaps a light switch. Anyone familiar with ZZT will be able to tell you that such a thing is impossible, so what does it actually do?

...it makes the walls color cycle for a bit. A real light switch rave. Small moments like this give Dr. Zeebo something simple to remember it by.

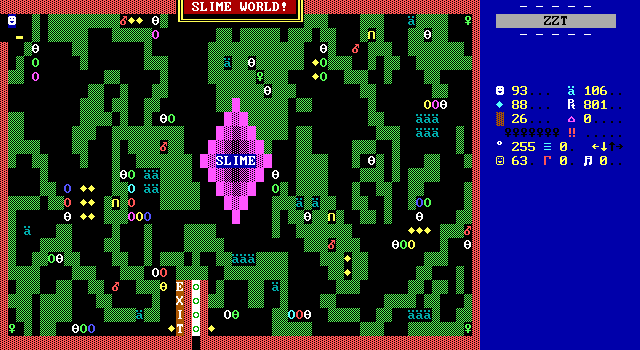

SLIME WORLD!

Despite the name, there aren't any slimes present on the board. It's all been pre-slimed. A messy arrangement of breakables gives an equally messy structure to a board that would otherwise be entirely open. Players get to tunnel directly to their destination should they have ammo to spare, or may focus on conserving resources and trying to prevent enemies from having a direct route to reach the player by.

Look closely, and you'll see that outside of the keys, one bullet to get into the room is enough to reach nearly everything else. Once again, Hewer leaves it up to the player to decide how they want to tackle a room.

Lots of ammo is provided, with bits scattered across the board along with a box of ammunition at the start to give players a jump-start. Early on ammo is much more of a concern, so it's certainly appreciated here.

More can be found in some chests too of course, but players better make sure they get it before they light any of the nearby bombs to blow up some leg-room for themselves. This is the other property of chests, they can be destroyed in explosions, forfeiting their contents. Hewer doesn't often do this, since all these chests were once just more resources that couldn't explode to begin with.

It adds one more thing to consider with how you approach the room. Do you need that ammo that badly? Can you light a bomb and while waiting for it go to explode grab from the chest? Or maybe you should play it safe and make sure to empty the chests before lighting the bombs.

The board does have a more contentious setup as well. This board repeats the same key which means a trip to the exit doors after each one. I don't think this benefits the game any. There aren't that many enemies, so by the end of it you'll likely be walking to a key without any worry of a few remaining 'pedes getting in your way. This kind of back and forth is best done with persistent obstacles like duplicating enemies or spinning guns. Perhaps if an object were spilling out slimes to transform the landscape there might be more of a reason to do things this way.

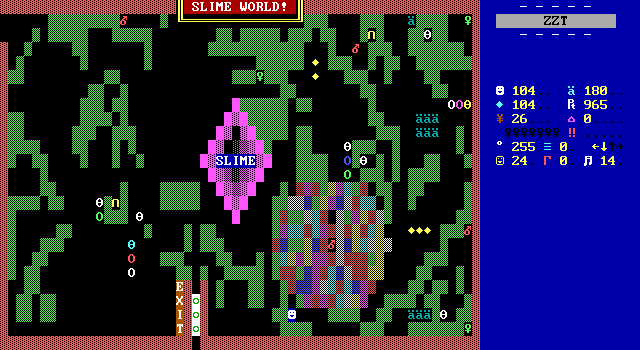

Another transporter maze similar to the starting board follows. Now though, Hewer is willing to up the ante, creating a tougher challenge by making the room dark and including more enemies than previously.

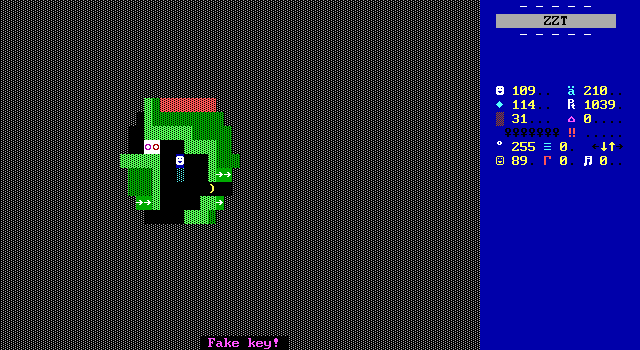

Fake keys are another fresh mechanic for the board, tricking players into thinking they need to get to one place when they should be heading to another. The only fakes here are ones out in the open so there's no risk of opening a door and needing to reload your save. That would be a bit cruel.

And although things are dark, there are still some really appreciable navigational aids. In torch light, players might not be very confident about where a transporter will lead. For guidance, some arrow objects are used to communicate that a transporter is a one way trip , while those connected on both sides get a line drawn between them.

Even when players can't see a transporter in their light, sometimes it's beneficial just to see some of the guidelines and know that if you try to head in that direction you'll reach a transporter.

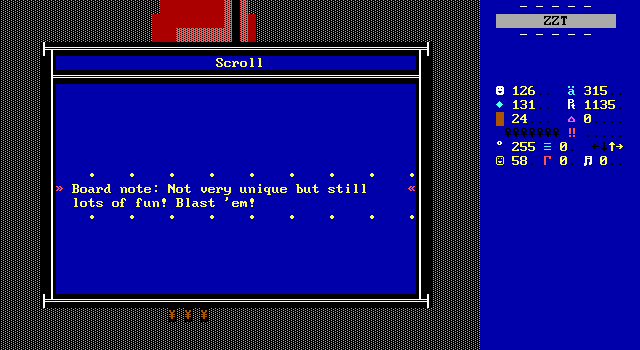

Players soon find themselves using their keys to enter the red caverns. In contrast to the much more open-ended action boards before this, here it's just a straight gauntlet of monsters as players go from point A to point B.

Hewer admits that it's not the most original concept. He's right though that it doesn't stop the board from being fun to fight your way through!

These caverns are the first time players encounter a new type of enemy. Here, some bouncers endlessly go from wall to wall. There's no information given to the player, making it up to them how they decide to approach the situation.

They don't actually do anything to hurt the player directly. If you shoot one as I did, it will deflect the bullet back at you with a rude "PING".

I'm not a fan of them and not just because I got owned by one. It's so weird to me to just introduce these things that only move back and forth in an environment where that doesn't matter at all. If this was an introduction to them before they showed up in more involved scenarios later, then sure. These guys however, never really make another appearance. Any potential they may have had as an obstacle just goes to waste.

Each of the rooms are closed off until players open a door. Hewer sees an opportunity for "enjoyable and unique" here and takes it. Most games would just have the door quietly open and disappear or maybe move out of the way. Dr. Zeebo has other plans.

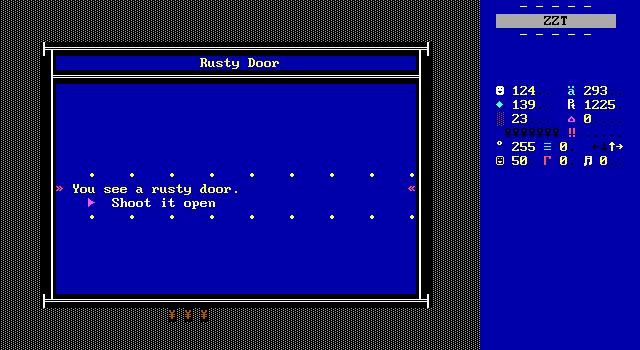

Each "rusty" door can't be opened by normal means, giving players a single option to choose for how to get past it, each with its own description. What would normally be nothing of note, is instead a humorous series of actions the protagonist suddenly proves themselves capable of.

One door gets shot open. The next has its lock picked. The third has a glass window to punch through and unlock the door from the other side. The final door depicts an exasperated hero's complaints being heard and the door vanishing with no explanation. It's a cute gag that really shows how capable Hewer is of making the mundane memorable.

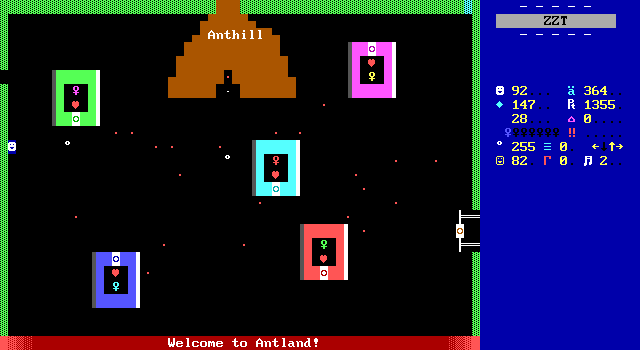

The anthill marks the second attempt at creating a new enemy, with far more success this time. These ants are the sole adversary on another key collecting board. They move slowly, following a pattern of seek, idle, random while looking to see if they can bite the player at each step.

First off, kudos to Hewer for actually checking if the player is next to an ant on every cycle. A lot of games of this vintage don't care to repeat #if contact over and over again which dramatically reduces the ferocity of custom enemies, especially when they're operating at slower speeds.

The ants differentiate themselves from other ZZT creatures by dealing less damage (just five) and also taking two shots to kill. The first hit causes them to stagger away from players for a bit before returning to their main loop.

For a board reliant on a single duplicator, the balance is remarkably good. With a considerable amount of enemies already on screen, and a fast but not maximum rate of duplication, I found myself having to alternate between running to grab the next key and having to stop and slim down the horde a bit. Everything here feels like a natural fit for what the board asks. Hewer avoids the more common and more extreme scenarios of enemies flooding the room or enemies being cleared away significantly faster than they spawn in.

Hewer also does something here that's so elegantly simple, yet has such a huge impact that I can't believe it's not common wisdom. The ant has an extra line of code to compensate for the duplicator spawn. The first thing the object does is move south three times as a one time operation before entering its main loop. This helps alleviate congestion, keeping the area where the duplicator first places enemies clear, and since ZZT won't advance code until those /s commands are successful, it's also an effortless way of preventing a source object from running any code before it's considered spawned.

For the ants, that's not a concern, but in other ZZT games, where maybe an enemy sends a message out when it's aligned with the player, the author can be confident that it won't fire from the source enemy that isn't meant to be in play. This is a technique to remember. I wouldn't be entirely surprised if it's been used elsewhere, but it's the first time I've ever noticed such a thing.

Speaking of noticing things, did you notice the anthill board had a mis-colored wall up top? I did! And for my keen observations I was treated to the first of a few secret bonuses. These only provide points, which keeps the game from being ruined by players suddenly gaining 1000 health and ammo (looking at you Fred! 2).

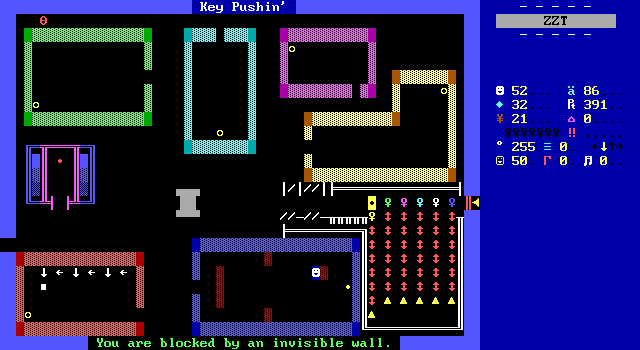

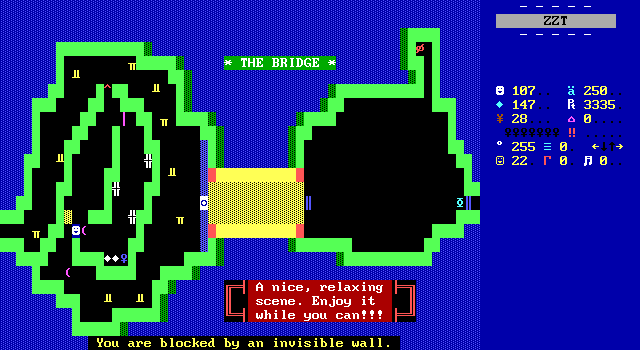

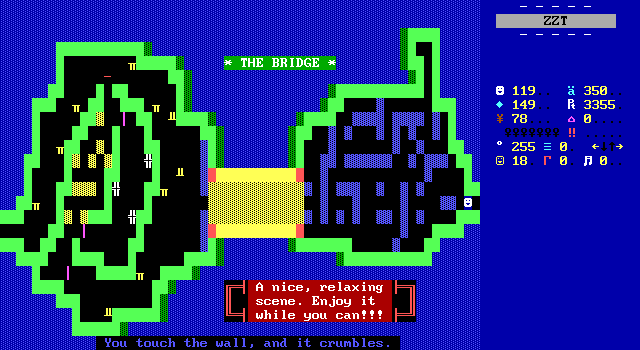

Beyond the anthill lays the bridge, another board whose looks are deceiving. This time the path to the key has a number of pushing objects that once again look like they're going to crush the player if they get too close only to do nothing at all. Though this time it's probably less of a surprise thanks to the text telling you to relax on this board.

There's some good use of invisibles on the left side. Once you're through the transporters, the path has just enough to make heading forward a minor obstacle. After taking the next transporter to get past some blink walls and grab the key, you need to retrace your steps, so hopefully you remember where things are clear lest you bump into any yet revealed walls. It's still nothing more than a time waster, but if a time waster gets me to use my brain to remember how I moved previously, is that still a time waster?

Any invisible wall philosophy goes out the window on the right side of the bridge. This is just a tiny maze whose only saving grace is that it's a tiny maze. A pouch with a considerable amount of supplies is an optional goal, with a scroll at the exit strongly encouraging players that skipped it to go back and get it while they easily can.

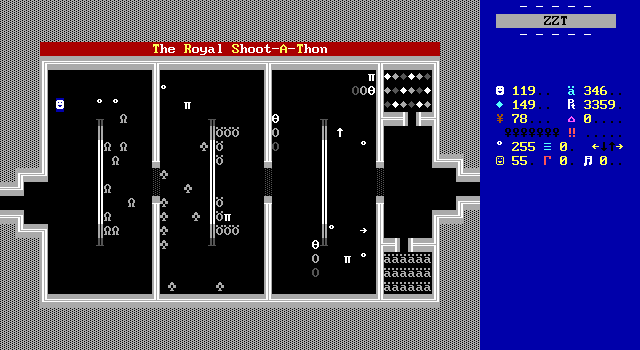

If you've been taking the game's colors for granted, the "Royal Shoot-A-Thon" offers a glimpse into ZZT's dreary late-90s future, or a budget PC buyer's past. For one board only, color is verboten. A scroll proposes that the game may have switched into mono mode, and then players are sent on their way through another animal attack sequence.

Just as always, the placement of enemies around the shape of the room feels deliberate. The zero-shaped sections match the creature's intelligence settings, allowing them to fan out slightly but not really reach the player. You get to engage on your own terms, and pick the initially identical paths to give yourself an advantage.

Up until now, the game has been pretty much exclusively action, with the only real puzzle elements consisting of non-dangerous mazes or finding an appropriate transporter. Neither of which had any way to fail.

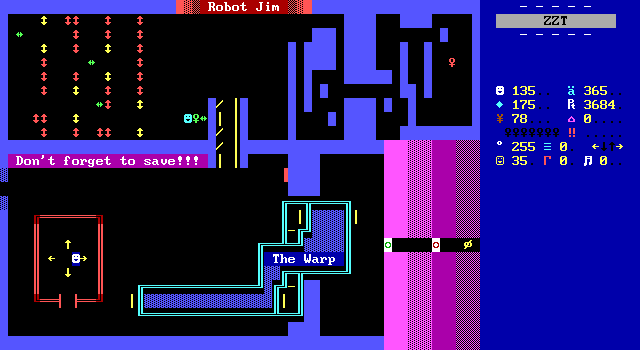

Enter Robot Jim.

Robot Jim is one of those classic remote-controlled objects that players use as a proxy for sections they can't access themselves. Jim can be steered with the arrows and push some keys onto a conveyor so players can continue.

Usually these boards are little more than a novelty. In City's Processing Department, the centipedes can't really do anything, and the only mistake you can make as operator is to push a key against a wall where it can't be recovered. Even in Nightmare, the smash hit released right around the time of this update, has a dud in the Sandman's workshop, where the only difficulty is in figuring out the unlabeled controls for the robot.

Hewer instead comes up with two different puzzles. One key is trapped behind some sliders, and the other, a sequence of small Sokoban-esque layouts. Neither is all that difficult, but I couldn't help but hesitate at times, double-checking my work to make sure I'd be able to push the green key out and to confirm I was next to the arrows I wanted to push to steer the robot. This works and doesn't overstay its welcome.

And for some extra fun, instead of a boring old walk to the the doors out, we've got "The Warp". Hewer keeps it silly by using transporters instead of yet another doorway.

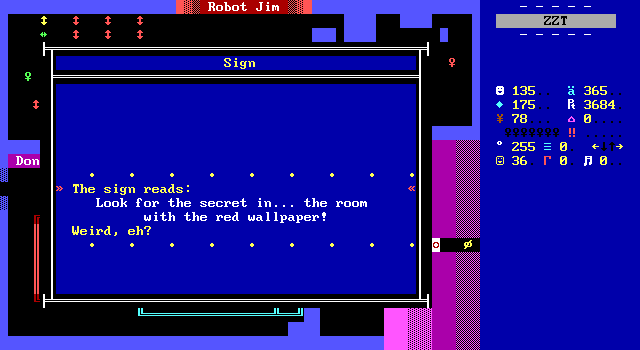

Also included is this not very cryptic hint about the location of the next secret room. This is a nice way to go about it. "Red wallpaper" gives you a color to look out for, but doesn't make it entirely obvious what you'll need to do when you see it. How long until it shows up? And will the player still remember when they'd want to, or will they be distracted by everything else going on in the board that they'll overlook it?

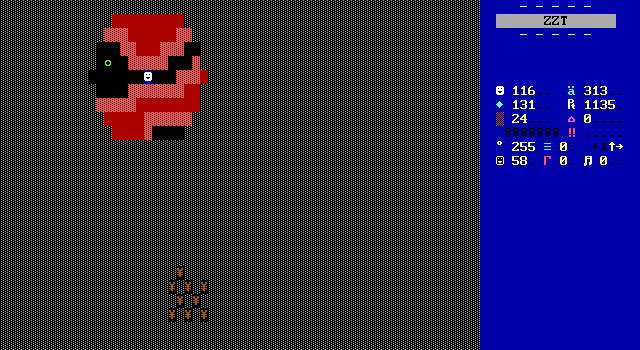

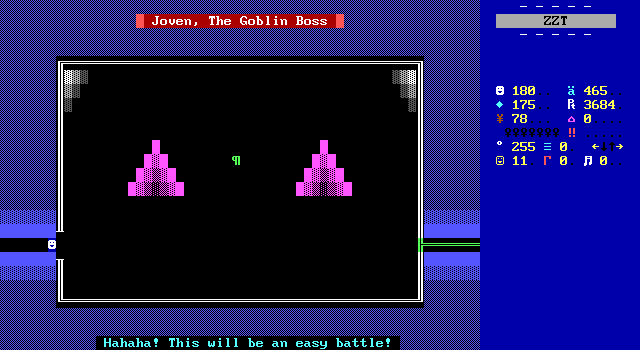

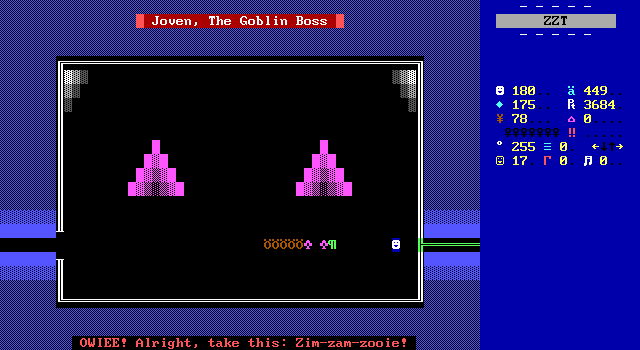

One of the ways Zeebo updated over time was the addition of boss fights. One in the 2.5 update, and a second in this release which players encounter here.

As Zeebo only has "go find this guy" as its story, Hewer has to come up with a reason on the spot for there to be someone trying to kill the player. Joven starts his introduction with a simple "this is my turf" before coming up with something more interesting. One of the upcoming boards is "Goblin Town", and Joven knows that to get through there, you'll have to hurt his friends, so he's going to kill the player first.

While things start out as a simple chase the player and shoot when aligned fight, Joven's magical abilities show up after a few hits to make the things interesting.

I love this dork. His spells summon in creatures to aid him that change as the fight progresses, starting with bears, before more challenging enemies (ruffians and then tigers) appear instead.

Wisely, they're all spawned away from the player, so holding down the fire button won't instantly destroy the summoned creatures. A well-placed idle after the :SHOT label and before the #ZAP SHOT and creature spawning prevents spamming bullets from accomplishing anything more than a stalemate.

Boss battles tend to be just okay, as the limitation of ZZT's tile-based combat limits effective tactics for bosses and player alike. Hewer doesn't do anything spectacular here, making a decent little shootout with a few enemies to draw the player's fire away momentarily. It's the characterization of Joven that makes the fight more memorable in my eyes.

He's no random lackey. Dr. Zeebo didn't hire an assassin. Yet he has a very valid reason to want to stop you, something you rarely see. It's hard to think of him as a bad guy, and I couldn't help but feel bad that I had to fight this guy until he gave up, knowing full well that Goblintown was very much in danger. Danger of me.

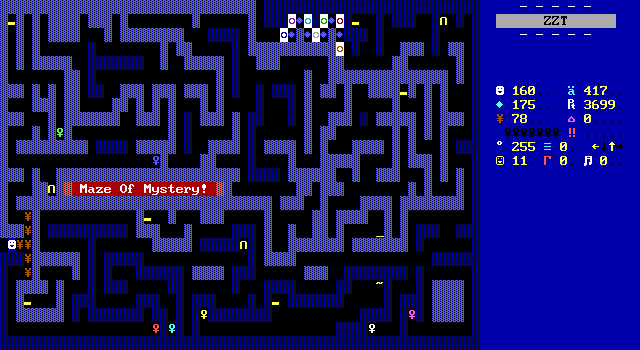

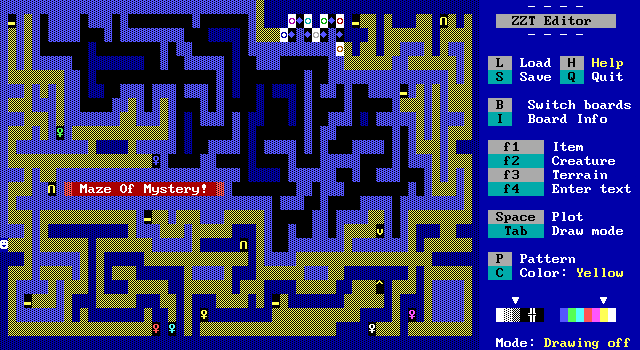

Oops it's been like two board since we had a maze, so it's time for another maze. This one is the worst yet. It's denser and larger than previous instances. Players are forced down corridors to get keys before they can leave. The reward for checking out dead ends is now gold bars that give points only (the health from gems is going to be far more tempting a benefit). It ain't great, though at least it's not dark, though the torches at the entrance make me wonder if at one time it was going to be.

The one saving grace is that it's not actually as big as it looks. Roughly a third of the maze can't actually be reached making the board shorter than it appears at a glance.

Break free of the idea that mazes are a necessary component of a classic ZZT adventure. The world will thank you.

The surprises slow down a bit here on this next board, one of only a few without a title displayed on the board itself. (The editor calls it "Doorways To...".) We've seen buttons to open doors back in Key Pushin'. The recent "warp" made exiting a more whimsical process and here that whimsy is found by blasting open the exit where some bombs have been placed. Even duplicated enemies showed up with the ants.

Quick thinking is once again rewarded, (see the spinning guns in Key Pushin',) this time by realizing it's going to be safer to press the switches currently devoid of monsters first, before too many enemies can make things more dangerous. The blocked off switches that already have monsters inside are a finite number, which may be tempting to get rid of early to lower the current monster count, but will lead to more genuine danger later from extra duplicated enemies.

The presentation is nice though. I dig the red diagonal walls marking the exit. And no, they are not the curtains for the secret room.

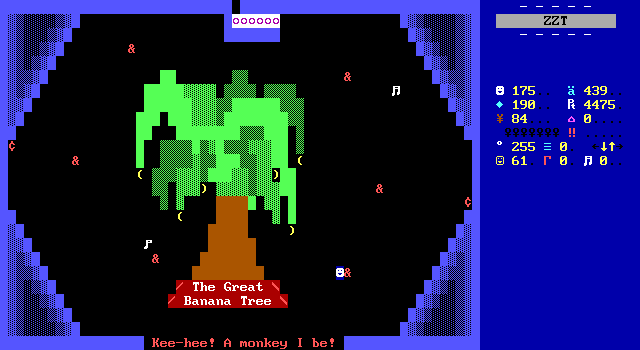

The surprises come to a full stop on this next board, which is immediately recognizable by anyone that's ever played Super ZZT's Monster Zoo. Just as in that game, players pick all the bananas off the tree and give them to some hungry critters. This time instead of grues its monkeys who are waiting to exchange a key for a banana.

I guess this board is kind of a time out. Things have been pretty non-stop in Dr. Zeebo, so it's not so bad to have a moment where you can catch your breath before jumping back into the fray. A nice little homage like this provides that break while keeping you smiling for being a good little reference-knower.