Choose Your Own Adventure

The defining feature of Knight's Saga is something that extremely few ZZT games have done since, giving players a real opportunity to guide the story.

There have been games with multiple paths through them, like NextGame 33 or Code Red. These games branch in very distinct directions, and very early on, offering multiple scenarios more than different possibilities for a shared one. With Knight's Saga, players always follow the story of Derek's false accusation of murder and the Dark Gladiator that stalks him. Your decisions are mostly rooted in dialog, deciding how he treats others, and what role he wishes to play in the plot.

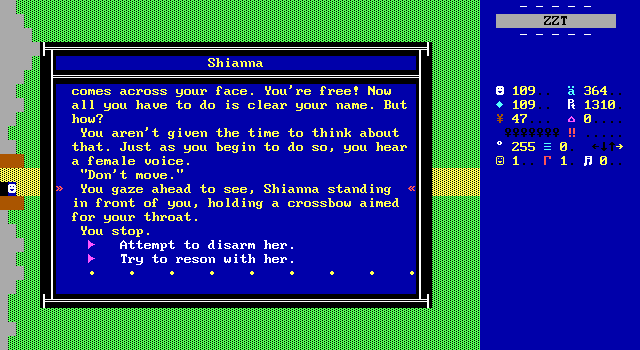

In some ways it's less interesting, as unlike those other games where the experience is unique 90% of the time, in Knight's Saga, replaying it to make other decisions, mostly leaves the game unchanged. Whether or not the player gets along with Shianna, they're still going to travel through the same forest. Even when the differences get more substantial, such as if Shianna tries to capture you for your supposed crime or not, she'll be waiting at the other side of the river, well aware that you're an innocent man.

This was originally going to be my biggest complaint. Every path eventually returns to a common spot. Yet actually, Hensley does eventually add one meaningful split to the game that changes the details of events for the rest of the game.

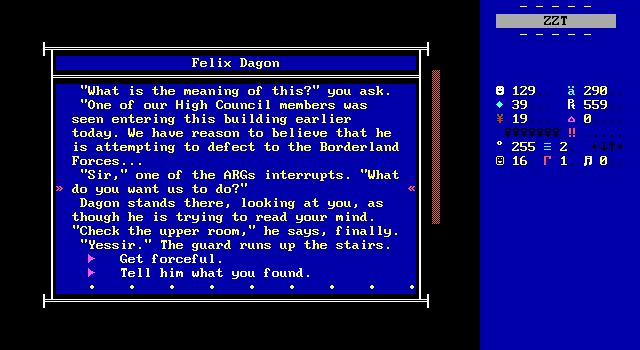

Ironically, it's the one choice in the game that players are mostly likely to believe isn't a real choice: whether or not to accept the mission to obtain the Talisman of Light from the castle. When the question is "Do you want to get the thing that will let us save the world?", rarely is saying no an option.

When Hensley's the one in charge though, yeah, do what you will. There's an entire section of the game that I didn't see by accepting the obvious mission. If Derek refuses to return to the kingdom where he's currently wanted for murder, it falls on Shianna to retrieve the talisman. Derek has to fight his way through the tunnel that runs under Mount Dragon rather than through the sewers into the castle. In turn, by the time he arrives, other ALM members have already done much of the fighting. It's the coward's route really, with the so-called protector of light being too scared to go where he's most needed, and instead becoming little more than one of many trying to fight off the demonic invasion.

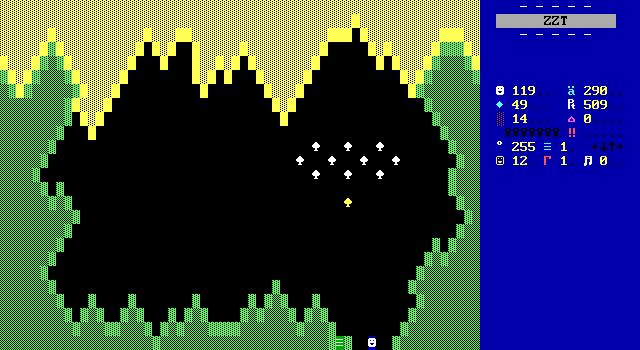

By the time Derek even arrives, the battle has already occurred, with the bodies of a number of demons littering the mountaintop.

Both options see Derek eventually facing off with the Dark Gladiator, but in two very different contexts. Namely, if Shianna is the one trying to obtain the Talisman, she fails in her mission, and the Dark Gladiator mockingly shows you her severed head as his latest prize! Needless to say, on this route, Shianna and the other ALM members aren't present when Derek reveals Dagon's crimes to the queen.

Which in turn has one final effect, without Shianna still alive, the final decision that determines your ending is no longer a choice. Derek, even when scared, has to uphold his oath and continue on as Gladiator. One can only hope he becomes comfortable fast, as the beings of darkness won't be waiting.

The tech required to make these dynamic plot points happen would be easy enough for anyone with a decent grasp of ZZT-OOP. We saw last time however, that Hensley didn't yet have that, and while I had hoped that might change for the sequel, it absolutely hasn't. Just as before Hensley uses no flags, still relying on keys on to get the job done.

That was a bit awkward before, having NPCs that gave you a key to start a quest #DIE afterwards, and then when players returned to claim the reward using another key they found to mark the quest as complete in order to access it. This time, Hensley wants to do more, changing dialog and sending the player to different places depending on the choices they make. Keys and doors alone aren't enough.

The solution he comes up with is an extreme one. Players make their choice and get a key for it as before, and then when a dialog branch needs to happen later based on that earlier decision, he puts down multiple doors with unique passages to convert key back to the appropriate dialog.

This means that if a character needs to behave in two possible manners, Hensley has to duplicate an entire board and adjust the dialog as needed.

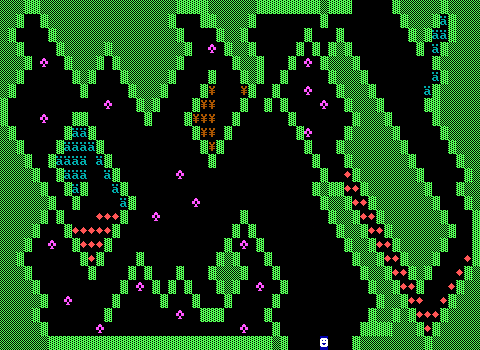

This has a number of unavoidable side effects on the game. The most obvious is that the board count is bloated, sometimes even more than necessary. For the first quest you have two copies of the forest entrance screen, one if Derek was kind about working with Shianna and the other if he was a jerk about it. Shianna needs to treat the player differently resulting in a split.

But Hensley wants the player to be able to navigate the forest as an open space which means players need to be able to return to their screen that had Shianna on it. In turn, the other boards for the forest which have no dialog whatsoever also need to be copied. The three boards of forest are forced to become six. It's only when the quest is completed that Hensley can place a passage at the end of each route that returns the player back to the castle where the split merges back together. This is kind of insane.

Alternatively, Hensley could have had the two characters converse on dedicated boards for it and then dropped a different key for each one. Players could then enter a shared forest, and the same multiple passages behind multiple doors system could have been used to handle the ending dialog split as well.

Either way though, this is an awful system. Hensley needed to put in twice as much effort if he ever wanted to adjust the gameplay boards that are split up. He's discouraging himself from making small improvements once a board is "done" and copied.

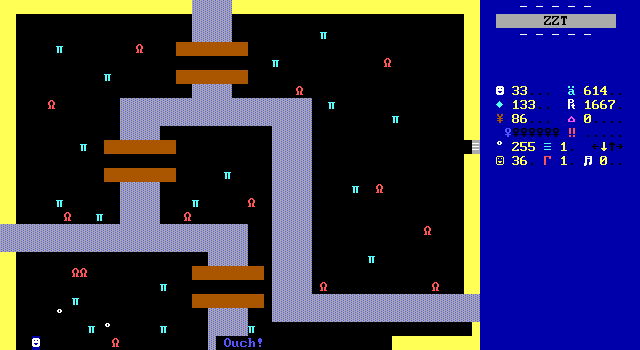

You can in fact compare the the two first forest boards and see some minor differences. The walls that make up the entrance differ, and the path where players are rude has extra torches scattered around as Shianna will be quite stingy with her torches if she dislikes Derek.

This technique also makes dialog adjustments more of a pain as well. Plenty of dialog remains identical regardless of what board it appears on. (The queen is going to congratulate you two for a job well done the same way.) Any typos found later would need to be fixed twice to remove them completely. Given how much effort Hensley puts into the game's writing, which goes above and beyond the previous game, adding an extra cost to editing dialog surely had some impact on the final text.

Thank goodness ZZT's editor lets you export boards or I don't think this game would have happened at all.

While most decisions have only a minor impact in practice, they feel more weighty when encountered. There were some moments where I really paused and considered what I wanted to do. The meeting with Shianna at the river in particular. I played on the path where I had been rude to her, and that had me wondering if I had made a permanent enemy or not. Even little decisions like whether to use an alias or not at the tavern on the kingdom's edge are the difference between having to fight and kill another mercenary or becoming friends over a drink. Emerging from the underground tunnels beneath the castle only to encounter Dagon had me opting to take my stand now, not believing he could be convinced to listen to reason. I managed to evade him and take down a number of Atherian guards before, so why not do it again?

The choices make the game feel much more personal, making players active participants rather than merely observing what happens to Derek.

.

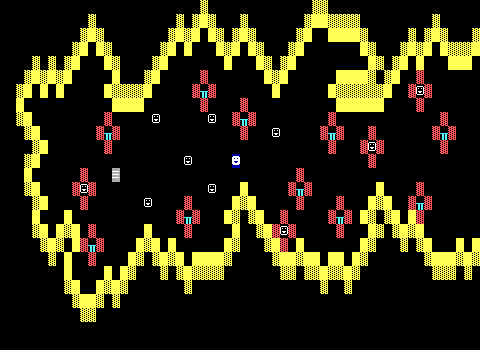

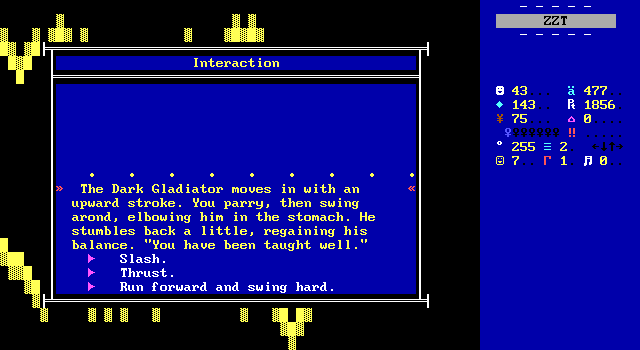

And we can't ignore the battle against the Dark Gladiator. The fight plays to Hensley's strengths, a menu-driven sword fight for the finale. We've seen this kind of fight in Question Mark's The Guardian, in which every enemy action gave players a list of ways to react, asking players to use context clues to determine which option was the most likely to lead to success at the moment.

Hensley only does this once, so it definitely avoids the tedium of repeating the same scenario with the same enemy every time.

As your foe here isn't some beastly abomination (merely a demonic abomination), Hensley gets to include banter during the fight, with the Dark Gladiator commenting on Derek's skill, or lack thereof. In return, Derek can try his own tough guy act, masking any difficulties in fighting, and boasting confidence as well.

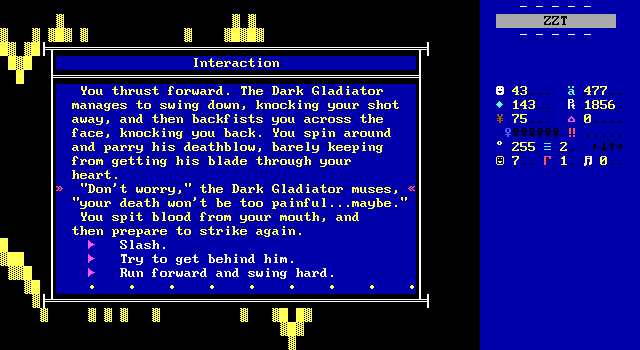

The consequences for mistakes are far more dire. Making the wrong play with the Dark Gladiator usually ends in an immediate decapitation. If you're lucky, you'll only be knocked prone and have a chance to dodge his next strike.

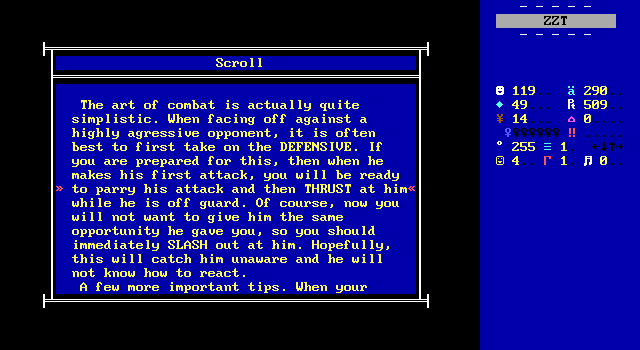

Making the correct decisions is a test of whether or not the player paid attention significantly earlier in the adventure. Way back when Derek was simply going to listen to a worried council member's fears, one of the only buildings outside the castle that can be entered is the office of the royal scribe.

The scribe mostly serves to integrate the history of the world that was a separate text file in Gladiator directly into the game, teaching players about the Knights of the Eternal Order, the prophesied Sundering (which is the subtitle of the unreleased third chapter), the Gladiator sword, and so forth. The rest of the building, true to Hensley's minimalist design is nothing more than some brown text used to suggest shelves of books. Save of course, for the bright flashing scroll collecting dust in the corner.

This scroll is the cheat sheet for your fight with the Dark Gladiator, with emphasis about how against an aggressive opponent you should prioritize DEFENSE against their initial attack. Make sure to THRUST before you SLASH. That sort of thing. Amusingly, these instructions suggest that rather than do any heavy sword attacks against a prone enemy, that you should do something quicker, like kicking them when they're down! Always uphold light indeed.

Not everything is so obviously communicated, with some other tips requiring more than just looking at capitalized terms.

It's hard to say how I feel about this method of teaching players how to win. It does come off as just giving you the answers and either you remember them or you don't, but I like the way it's more than remembering the order of capitalized words. It is written as a generic strategy to use in combat, and the order doesn't perfectly reflect the actions the Dark Gladiator takes. I was repeating "Thrust. Slash. Kick." to myself over and over as I played, not expecting that there would be more to remember when it mattered.

The only real complaint is that this information is just... lying on the ground somewhere? The delivery method leaves a bit to be desired. Surely there's a better way than this. But I'm at a loss as for what. I mean, a character could deliver the information at some point (and in fact, the scroll is credited to Garadene, the ALM member that fights with Dagon in the throne room), but that's not all that different. I could see splitting the information up over the course of the game, with Shianna giving you one tip, and the mercenary in the Borderlands tavern another, which would certainly be more natural. It could be integrated into the choices you make, requiring Derek to make himself likable for others to share their knowledge, but that would come at the cost of there being no wrong way through the game, replacing player freedom with "do this so you learn this".

Even if not a perfect system, Hensley's implementation of it is solid, and makes for a very satisfying battle. Realizing that you need more than just capitalized words creates a sense of tension when you really have to rack your brain to try and remember exactly what the scroll said. I'll take this over another run and gun, an RNG-dependent RPG engine, or Hensley's previous method of merely touching the enemy to start the fight equaling victory. It's different, and well executed, and I think a valid option modern ZZT worlds could consider as well with a little refinement.

The Bugs Are Back

With the first Gladiator game, Hensley's grasp of coding was shaky at best, requiring him to find non-code solutions for things ZZT is more than capable of. This meant keys instead of flags, NPCs being unable to ever update their dialog, and NPCs that provided supplies having to stop existing to prevent players from getting infinite items. There were a few passage errors too that through luck never actually broke the game. In the end, the writing was good enough to look past of it. Besides, it looked to be Hensley's first game, so cut him some slack.

For the sequel, you can expect more of the same. Along with some new issues, thank make Knight's Saga a disappointingly less well-built game, that once again gets to coast on its good graces thanks to the much more exciting story and stronger focus on character interaction. Still, it's always a let down when the issues of an author's earliest work continue to persist. You'll find a number of problems with the game that are even more obvious than in its predecessor.

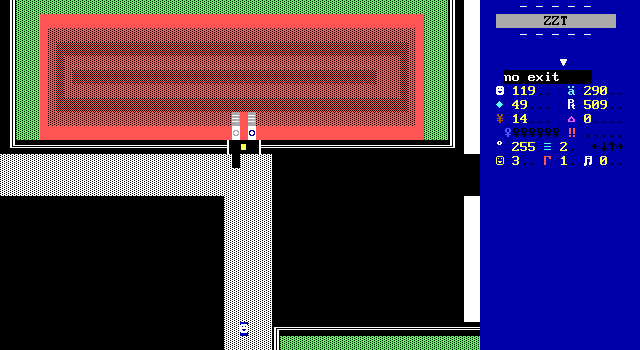

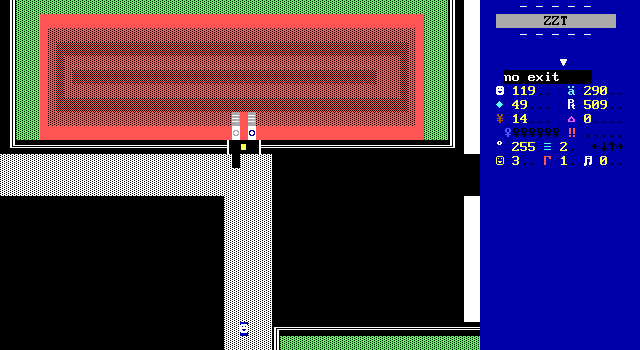

The first big problem appears before Derek even begins his first quest. As quickly as you gain access to explore the castle town, you may very well lose it. The northeastern board mistakenly has no board exits set, forcing players to move counter-clockwise if they want to see the rest of the town.

Luckily, the board players get trapped on is the one that advances the plot, allowing the game to continue as intended rather than rendering the entire game unwinnable. This is a pretty severe error though, as vanilla ZZT has no cheat to forcibly change the current board. It's a fifty-fifty chance that anyone playing the game got to see the entire town. For the unlucky ones, they had to either restart the game from the beginning, or do some ZZT surgery, renaming save files and using ?+DEBUG to open it in the editor and change boards.

All that effort would be for little benefit too. Players won't know that all they're missing out on are some basic shops in a game that keeps players as well-stocked as its prequel.

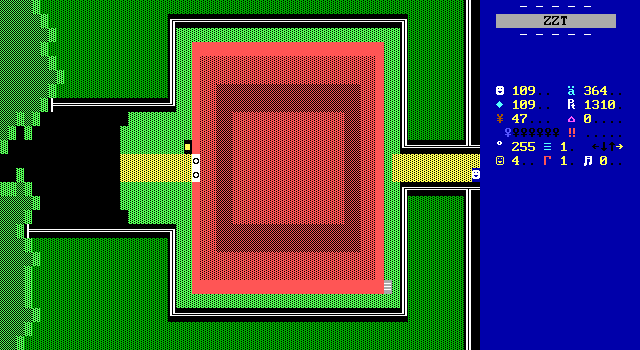

One of my pet peeves rears its head too of course. Some games get spared this indignity, but if your Closer Look gets a section for bugs, then I get to gripe. We've got us a mis-aligned exit. There's this nice path for players to use as a guide for where to enter the board from, and then they wind up bumping into a wall on the other side.

In a game that already had some outright missing board connections, I had a brief moment of panic that this was going to be another one, and one that couldn't be worked around.

Knight's Saga also continues its predecessor's tradition of not understanding how ZZT's passages work. Both games have a tester list. I will never understand how these continue to pop-up in so many ZZT games, even otherwise high quality ones like this.

Here, when Derek is making his way out of the castle dungeons, he gets to skip a board with roaming guards (lions) and a few keys to grab before reaching the exit, instead, starting on the exit and reaching the doors on the other side.

Derek Knight Vs. The World

Little has changed in the gameplay department. It's as perfectly adequate as ever. Except now it's in the company of some great story scenes that also give players the opportunity to make decisions themselves. The rising tide does not lift this boat, leaving it feeling adrift. Barring the final trek through an underground waterway, the action of Knight's Saga falls a bit flat as the one (intentional) aspect of the game where Hensley doesn't really show any signs of improvement.

As before, there aren't really any clear faults to find with the gameplay. It just continues to be the weakest part of the game. I found myself in a hurry to get through it now, thanks to being much more interested in seeing where the story went, caring more about the destination rather than the journey.

The choices which make Knight's Saga what it is, never really have an impact on these environments. They come off as detached from the rest of the game, as if one were to just grab some boards from Caves of ZZT to fill the space between story beats. About the only exception is right at the beginning, where there's a small generosity for players that happen to be rude about working with Shianna. The version of the forest for Derek (rude) gets a few extra torches scattered around to compensate for the lack of support received from Shianna.

It wouldn't be an easy ask to find ways to integrate the story decisions into the gameplay sections, but the first game did have peaceful NPCs that sometimes showed up during these segments. The sequel scraps them entirely. I think there could have at least been some small acknowledgment of current events. Derek on the run could meet a traveling Borderlander that's unsure if they should trust him, providing an opportunity for players to consider if they wanted to break ties with Atheria completely or not.

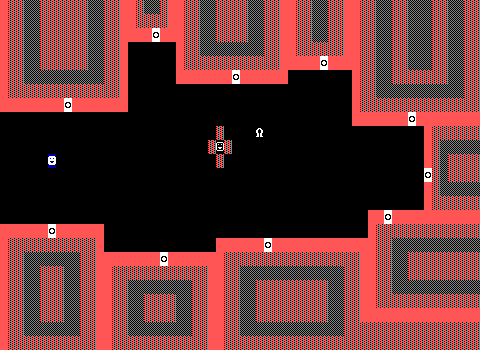

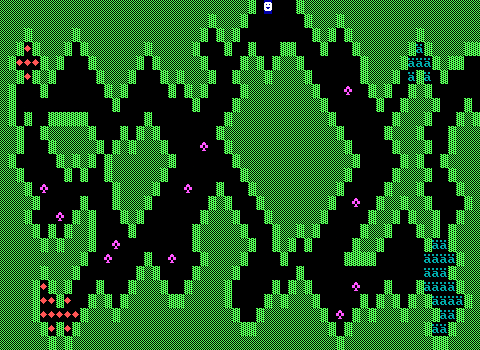

The locations Hensley uses for action haven't shown much variety, and that trend continues here. Multiple forests, and then some dark caves are what you get, again something you'd expect to find in pretty much any ZZT game. The lack of growth between games makes it more of the same, now even more simplified, removing a lot of the key collecting and button pushing that at least meant players had to spend some time on each board. Now things are streamlined a bit too much for my tastes. It's as if Hensley has begun to see these parts as a formality that just get in the way of the storytelling that he actually wants to do.

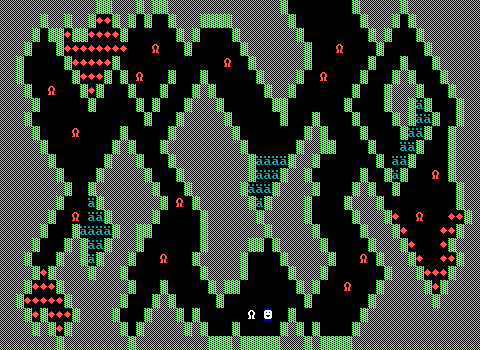

The northern forest is made a bit smaller than previously, ditching the elven village, and any sense of non-linearity. There's still some exploration to be had on individual boards themselves as players still have to find the path forward by torchlight. On the plus side, it's easier to actually navigate the space as the branching paths quickly reach dead ends and contain no other branches to keep players off the main trail. The simplified designs have a cost however, gone are the alternate exits from boards that lead to large treasure caches that tempt players to make sure they comb every inch of their current region.

Things are also a bit forest heavy early on. As Derek's mission doesn't require him to climb Mount Dragon or brave its hidden tunnel you only get green. This is followed up by the chase to the Borderlands, which is now a forested area as well. While it's definitely a more attractive space than its former status as an empty desert maze, the second forest is really no different than the first.

It is at least larger, and does provide a choice of two paths through it that link up at the exit. Both paths contain only ruffians for enemies, with scattered supplies which players will already have a surplus of. Most of the game's action sequences inevitably dull the excitement of the story unfolding around players. A break from reading text can be welcome, but the world of Atheria fizzles out pretty quickly when you're not reading, devolving into the generic.

This wasn't so bad previously, when Hensley had the benefit of the game (at least presumably) being his first release. Here, you'll wish it got even half the love put into the game's dialog.

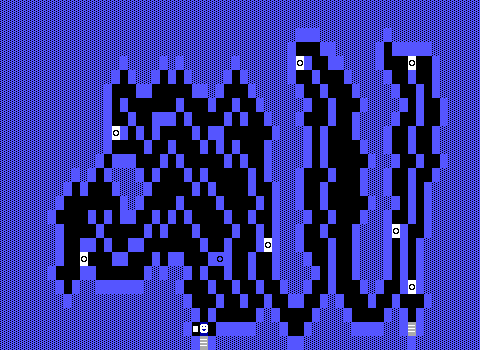

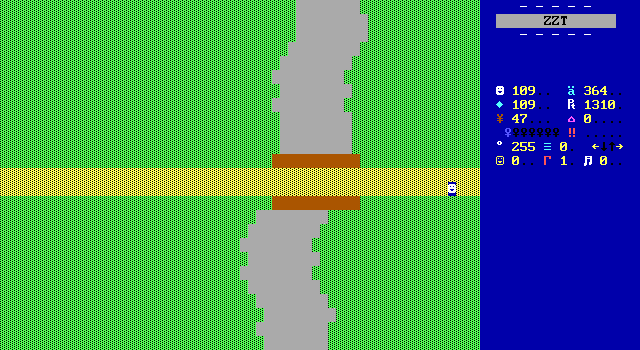

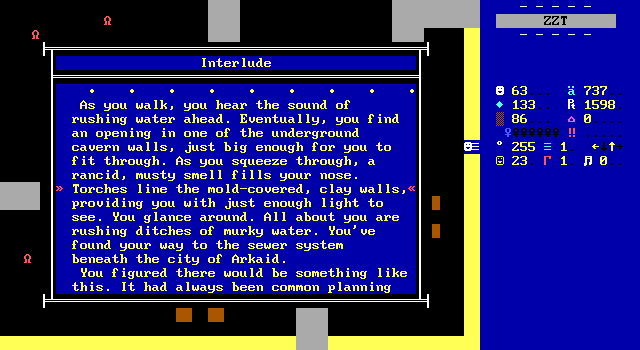

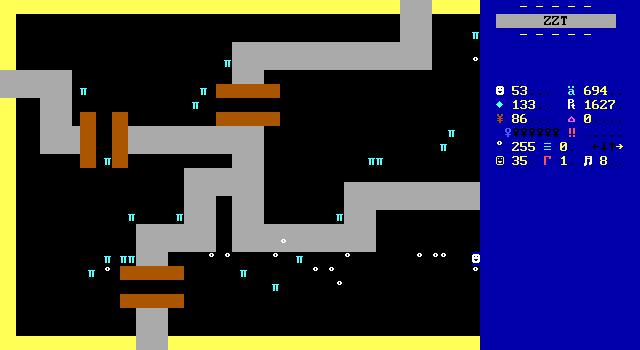

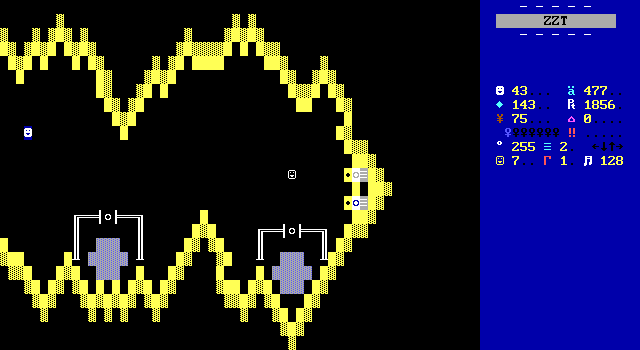

Only the secret waterway is able to improve on the designs of its predecessor. This sewer system that connects with the castle as a hidden means of escape in case of invasion is a much more original setting for action. It also ditches the dark rooms in all the forests, letting players actually see where they're going. So much of the gameplay in this one happens on dark boards that make it hard to appreciate their designs.

The waterway also gets some nice introductory text to let Hensley do what he did a lot more of in the last game, turning hollow rectangles into detailed spaces. You wouldn't know it by the shiny yellow walls, but Derek is inhaling so many mold spores right now. As expected, the text does wonders to making the sewer a much more disgusting and unpleasant place to be than the shiny yellow walls or a ZZT game made only with editor-accessible colors.

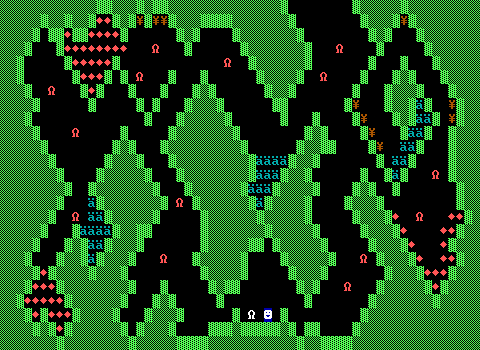

It's more than than just the set dressing. These boards take a new approach to their layouts, with a mess of canals dividing the boards into smaller chunks accessible by bridge. The first screen only puts the player up against Atherian guards whose swords are no match for Derek's which can shoot over water (don't ask). It's free EXP here as the lions do have their intelligence increased a little causing them to cluster together and align themselves with the player who can just stand on the opposite side of the water and shoot without repercussion.

The shooting gallery is quickly addressed, with the next board's interlude revealing a new enemy in the form of elven archers. Shooting over the water becomes less effective against enemies that can shoot and have their intelligence turned down so they don't stay aligned with players for long. Impatient players (me) won't want to put up with constantly missing shots due to the range they're taken from and will find themselves taking damage fighting closer than necessary to move things along. Deciding when to push forward and when to hold back using the water as a barrier is the most involved the action gets as well as its most fun.

Final Thoughts

The first Gladiator got me by enamoring me with its descriptive writing to make otherwise average quality boards that much more appealing spaces to be in. Knight's Saga redirects Hensley's talents to the story itself, making for a rare instance of a well written plot. You won't find self-deprecating humor or unexpected wackiness to deflect criticisms of a serious game not succeeding. Hensley is genuine and confident that his story is going to be appealing to players, while inviting them to provide their own input. If the series is indeed inspired by tabletop roleplaying, the branching points would all be sensible spots for a good GM to set plans for how the players might want to take things. He's able to naturally maintain the course of events that he wants, while letting players feel like they were the ones leading the way forward.

The branching paths through the game, both with and without returning to the starting path make Knight's Saga very unique for a ZZT game, especially in the 90s when most that dared attempt even the most basic alternate scenario found themselves with unreleased games or cut down ones (reminder that the 33 in NextGame 33 is because it's only 33% complete). Despite duplicating boards and doubling up on dialog, Hensley's branches are more like detours, but they feel significant regardless. Choices have some consequence, no matter how small, which is enough to give players pause when they see hyperlinks to really consider how they want to approach a situation.

On your first go, it works even better, as you have to wonder just how different things could have been. Players that opt to make a break for it immediately when Dagon calls for your arrest can't be sure if it was possible to talk their way out of the situation. Infiltrating the castle or immediately heading to Mount Dragon suggests some huge differences in what might happen, and is reflected in the adjusting of how the game ends. Despite continuing not to use any flags, Hensley still manages to make an adventure that has more possibilities than ins peers.

Knight's Saga, really, the Gladiator series, is a new favorite for sure. While part three never happened, the two games here tell a complete story, setting up a sequel in only those most basic of terms: "You haven't seen the last of me!". Even as an incomplete tale, I cannot recommend them enough, especially Knight's Saga, with its great story, well-written characters, and branching paths through the game. There's too much to love here to let the lack of closure stand in your way. Nostalgia is a big part of the appeal of a number of 90s hits, but this one which holds up incredibly today seems to have fallen through the cracks. Don't let it slip you by!