It's time for another patron pick, and this time the winner was a decisive victory. The freshly added option for 587 Squadron, an arcade shooter that hearkens back to the mid-90s ZZTer shooter craze took a solid lead. But throwback or no, the game excels at taking a far more nuanced approach to how to handle the realities of ZZT's limited capabilities for the shoot 'em up genre. Like any more modern ZZT world, there's a much stronger focus on keeping the game fun first, rather than prioritizing oversized ships or other gimmicks that look better on paper than on screen. 587 Squadron aims to do one thing, and to do it well. In 587 Squadron rather than piloting a fighter jet for a game revolving around air-to-air dogfights (like in Dogfight 'natch), you instead pilot a bomber, shifting the focus onto taking out targets below.

Agent Orange's new approach turns the genre on its head, deviating from established Space Invaders arrangements of planes to an overhead perspective with ground based targets to eliminate and enemy planes to be avoided rather than shot down. The change in focus allows cleanly working around the myriad of issues earlier shooters were plagued by. Shooters traditionally had their Catch-22 with regards to ship size. Big ships made it easier to to pick off tiny targets with their shots capable of covering a wide area, but came with a cost of it then being very easy for the objects that make up your vehicle to drift apart from each other or jumble together in an ugly mess. Single object vehicles meanwhile have no potential to go to pieces, but introduce a lot more tedium as their shots need to be rapid enough to get past enemy fire, yet also spaced out enough that an enemy that moves out of the way has empty tiles to move back into.

A few others such as Space Fighter: Mercenary opted for a more open- approach, having players steer their ship all across the board with the actual player and controls tucked away in a corner. While this at least meant being able to fire at close range, it's just as easily annoying, if not even more-so when the enemy ships go from moving side-to-side, to just moving anywhere they please. Seemingly there was just no way to with these games, forcing authors who wanted to utilize such engines to make sure that their games had non-vehicular combat sections to give players a break, and hopefully get them more invested in a game whose primary engine would rapidly lose appeal the longer players engaged with it.

These issues held the genre back in ZZT, with little innovation to the genre since its heyday. 587's only real contemporary game to compare to is PogeSoft's 2020 release Metal Saviour Bia which features two alternate takes on the shooter. The first of which has players steering their ship by moving enemy ships towards a crosshair, simulating a first-person perspective and using the movement of the enemy to create the illusion of your mech rotating. The second is closer to what Agent Orange came up with for his game, having you move around and press shoot to destroy whatever you're next to.

Jam Session

587 Squadron is one of only a handful of ZZT games to be created for a game jam that wasn't a ZZTer hosted event. It's also the only ZZT game that I'm aware of that was created for multiple jams! The game originally began as a short demo created for the 2021 DOS Games Spring Jam, featuring some placeholder art and four playable levels, albeit without the briefings or any story components included.

The second release for GBA Jam 2021 expands on the demo and includes basically everything in this final release of the game. It has the distrinction of being the first ZZT game released for the GBA.

The final "Z" edition was released a month later, adding in a hard difficulty mode for the real sickos out there.

If you're just picking up the final release to play at your leisure, the jammy-nature isn't apparent. The gentle development cycle rather opting for a demo rather than rushing a full release makes this come off like any other ZZT game, one free of obvious cuts or glaring flaws that couldn't be handled due to time restraints.

Though looking it for the purposes of documenting what the game does and how it does it, there's something to be said of ZZT games being made first for those outside the community. There's a skill to recognizing what isn't so obvious to those who haven't played ZZT worlds before, and it is not an easy one to train. From my perspective, there are both decisions and assumptions here that I think would add some amount of friction to those ZZTing for the first time. But at the same time, it's hard to say how far one needs to go to communicate things, and how to do so efficiently enough that you're not accompanying your ZZT world with a tome explaining why you're a white on blue smiley but you're also flying a plane, why the HUD is full of things that have nothing to do with 587 Squadron, why you have "100 health" but that number doesn't change when your plane takes damage, why you can crash into things you should be flying over...

For those playing DOS game jam submissions, "This engine from 1991 has some quirks" is an obvious statement. I'm sure they were all happy to to not have to write a custom boot disk to free up conventional memory. They've dealt with worse.

The GBA side is a bit harder to tackle. Seeing a screenshot of 587 Squadron, and saying it's for DOS will be met with nods of immediate understanding. Seeing a screenshot of the GBA version and saying it's a GBA game is considerably stranger. To this end, the game's instructions emphasize the controls as being operated by the player element, and includes a tutorial mission so you can wrap your head around things without worrying about needing to restart.

Its Itch page additionally brings up how the game is a ZZT world converted to the GBA with a special port of the program. It warns of potential contrast issues with the palette on an actual GBA screen, (I mean, that's authentic to the GBA,) and goes out of its way to first state that you control a "little white smiley" that uses touching as a way to interact.

Of the 44 submissions, the game placed 22nd overall[1]. From the judges' feedback, you get a mix of opinions on display. It's called "fun & playable", "quite interesting", and the use of ZZT is called "a nice surprise". Criticisms cover the game feeling punishing for game overs requiring starting back at the first mission, (an OpenZoo GBA issue, though one easily rectified with a password system or stage select,) the difficulty of seeing such tiny characters on real hardware, and the graphics looking more like one player would have expected from the GameBoy Color rather than GBA.

At the very least though, none of them seem lost from any of the things non-ZZTers wouldn't know. You need to have at least some faith in your audience.

Operator's Manual

Engine games made for vanilla ZZT often run into trouble offering up enough variety to engage players for the entire game. The inherent simplicity of engines that replace player-element focused gameplay entirely tend to not have enough depth to make the seventh board feel substantially different from the second. And while 587 Squadron doesn't have too many mechanics to introduce, the variety offered up across its ten missions is still higher than expected. Window dressing with touches of story between missions, along with some creative structures to fly around during them help the game go beyond the low expectations of the 90s, and reach the standard that modern ZZT games are held to.

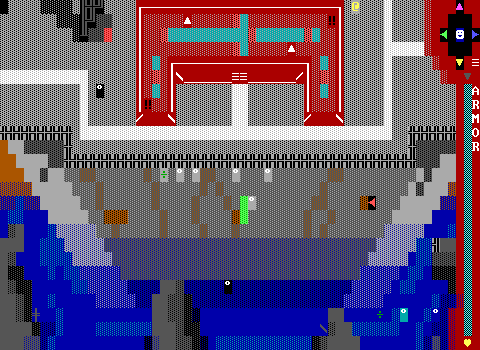

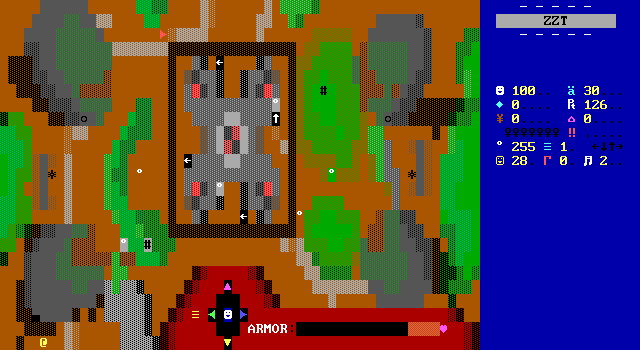

Nine of the game's ten missions sticks to the same formula. Your bomber flies overhead various enemy buildings, be they research labs, aircraft hangers, or generic bases. These structures have one or more blinking red fakes to indicate weak points which need to be bombed by pressing space as you fly over them, dropping a bomb that immediately explodes as a brown fake, turning the spot below into a crater, or at least rendering it inoperable.

The enemy is none to happy about this and has their own defense to shoot your plane down. Stationary anti-aircraft cannons are the most popular, though you'll also have to deal with moving guns, enemy planes, and bizarrely what I can only read as "very very very tall fences" that exist just to get in your way.

For the sake of the game's art style, and for player time, these little targets are very small, almost entirely consisting of individual tiles rather than clusters that would need multiple passes to take out. This makes your plane's capabilities remarkably surgical, striking only the tiniest pieces of a building to render it entirely unusable. It also means there's very little room for error.

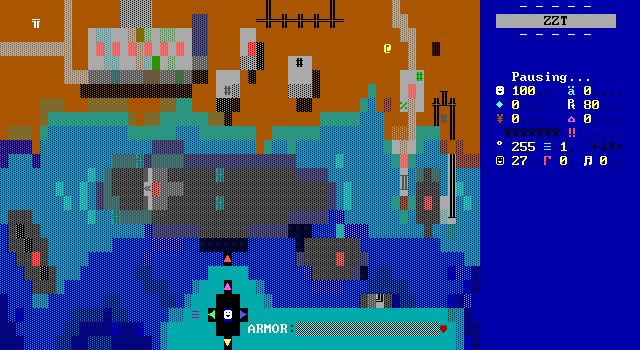

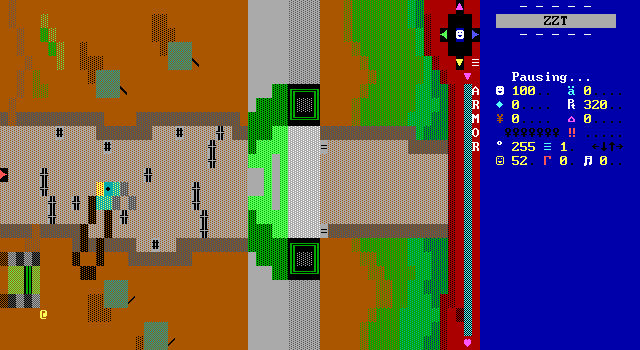

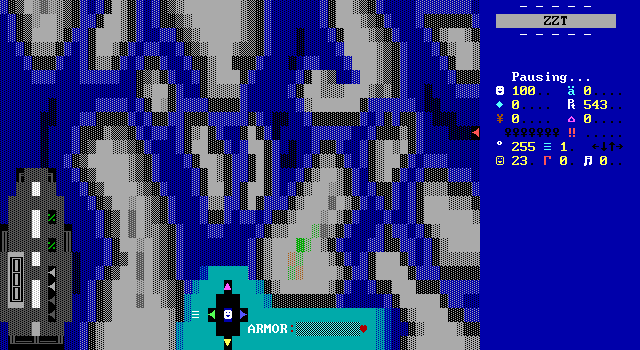

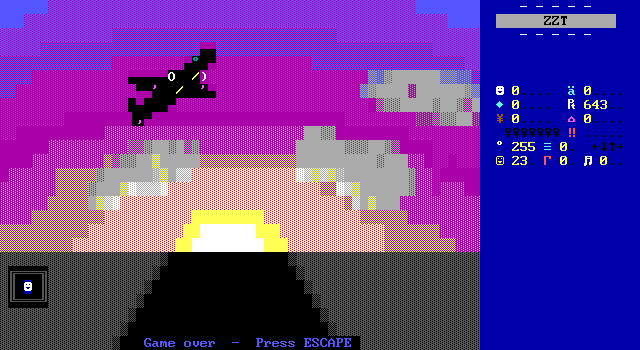

Missions may not have a hard time limit to complete them, instead relying on limited health and ammo to bring your efforts to a halt. Your plane's armor is repaired between missions, utilizing the traditional ZZT shoot 'em up health meter consisting of breakable walls that are chipped away at every time your plane is hit or hits an obstacle. The number of bombs you have available varies with each mission, with additional tweaking based on which of the three difficulty levels you're playing on.

The amounts given feel fair enough on normal. Just don't plan to win by a carpet-bombing strategy. Some missions equip you with a minimal number of bombs for story purposes, so watch your aim!

There are some small high score chasing strategies as well to encourage replayability beyond playing on a higher difficulty. Upon completing a mission, you'll get bonus points for any bombs you managed to save, with tweaks to their value so that players on easy don't get high scores just by not needing the extra munitions. Playing on easy mode also slows your plane down to cycle two, offering more time to react to an incoming collision.

The controls rely on the player being placed in the center of the usual crosshair of arrows, spaced out a bit so that player bullets can strike them. This means saving mid-level is permitted if necessary, though I get the feeling that the intended play-style is to only save between missions. The method of steering caught me a bit off guard, I expected to use left/right to turn clockwise/counter-clockwise, only to discover the directions are absolute. Instant 90 degree turns are a given in ZZT. Being able to make a bomber do a 180 at any time is a different story.

Turning on a dime gives your plane provides some fantastic levels of course-correction. Turning around instantly makes for some stylish moves to dodge enemy fire or spare yourself the embarrassment of striking an immobile structure. This allows for some fantastic saves, as the the safest tile to be on at any given moment is the one you just left as it's least likely to now be occupied by a projectile.

Despite the theoretical agility, flying a bomber through while being attacked by anti-aircraft guns and fighter planes is still not an easy task. It's hard to say whether your plane or the enemies are the biggest challenge to overcome in order to complete your mission. The plane may react to commands immediately, but the controls themselves have a moment of delay when returning to their original position. In more frantic moments, the urge to hammer on the keyboard until you're safe will only make a bad situation worse. Some inputs may not be sent to the plane at all, and due a strange oversight in the controls' layout it's possible for players to move a little too quickly for the input arrows to keep up, causing the actual ZZT player to slide out of containment, and into a corner.

As frantic as the game gets, it thankfully doesn't happen all that often. To cause it, you have to press the same direction you last steered in just as the arrow object moves back into its initial position and then turn away from that direction. In practice, it's only going to happen when you panic mash to try and get out of a bad situation, but there's both fixes via changing the layout as well as through code.

Blocking out the corners of the box the player is confined to is all it would take to prevent players from desyncing from the controls. This would alleviate the worst part of the issue, eliminating the possibility that players suddenly find controls not working because they're not actually pressing anything. You'd still get dropped plane inputs, walking into walls instead, only they'd be limited to just one before the plane controls shoved the player back to the center again.

The slight unresponsiveness added as the control objects have to take one cycle to shove players back to neutral can be eliminated entirely through code. By making the arrows #WALK away from the center, it's possible to have them #GO OPP FLOW when they player comes into contact with them, pushing the player back to neutral while also moving the arrow itself back to its original position all within a single cycle. Admittedly, this technique isn't well-documented, so more often than not if you see a player being pushed around by arrows meant to move something else on the board, they're most likely going to have this delay. Play these kind of games long enough, and you'll adapt to it.

Crashing is inevitable regardless of how accustomed you are to the controls, especially when you're too busy hammering the spacebar to drop bombs. When your bomber bumps into something, it takes damage as if shot and then waits patiently for you to steer it. It's a very polite way of letting players recover from their mistakes, giving them a moment to think about how to resume play. The alternative of constantly whittling down your health as you push against an immovable object would mean this already quite challenging game going into frustrating territory.

The lack of ramming does have its own share of ramifications though. Much like how players shooting at centipede heads will often see them turning out of the way of a bullet because it's an obstruction in front of them, the bomber too can crash into bullets instead of being hit by them, resulting in an uncanny moment of hovering in place, awaiting new instructions. Unlike buildings where endlessly trying to go forward would be rough, I do feel like the bomber should be checking if its obstructions get out of the way and then continue going forward if it's clear. (My brain is insisting on considering an over-engineered solution with temporary invuln time, but I can't vouch for how well that would feel either.)

The obvious strategy of minimizing time spent flying over targets is to just drop bombs liberally. Shooting in any direction (pressing space is obviously preferred) will make your plane drop a bomb and blow up the tile it last passed over. Again, be mindful of the latency as the bullet you fire needs to then shoot an arrow to tell the plane to do so. Getting the timing down on bombing is essential, and it feels really nice when you get a good rhythm going, managing to take out several targets in a row on the first pass.

Nothing is too sacred to be blown up in 587 Squadron. Missions never ask the player to go out of their way to not bomb something. There are no captured POWs, or active combatant on your side to keep safe, so if you have bombs to spare, nothing stops you from leaving a trail of destruction behind you. Very quickly though, even on normal difficulty, it becomes clear that you need to get your timing down to save ammunition.

A Well-Painted Miniature Army

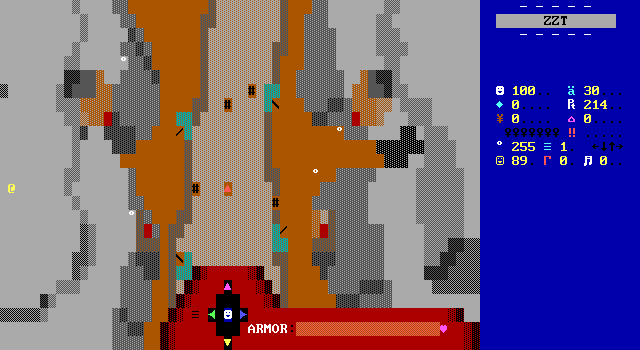

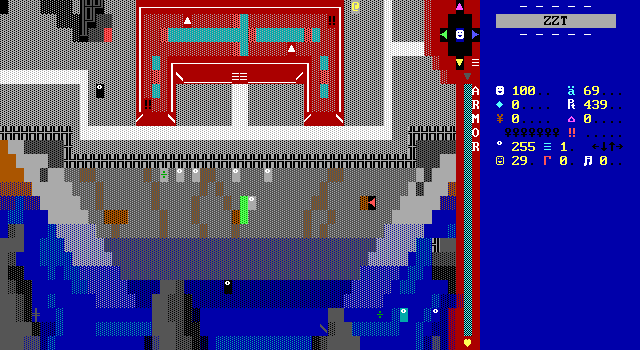

The game's engine is one that could have conceivably made in the mid-90s alongside those other shooters. The art style of the game is definitely modern. given the necessary restrictions on the game's graphics to support the engine, Agent Orange's visuals are quite impressive. The game's island setting offers players a chance to admire and explode beaches, canyons, airstrips, and fly over a dam from a dizzying height. It's not easy to convey a sense of height in ZZT, yet 587 Squadron does so repeatedly, elevating (pun not intended) the appearance of missions in ways that make them more than just map screens you can fly over.

As a ZZT game, there's a tremendous difficulty in making art for an engine like this where the majority of boards have to be made of fakes. Anything that is solid, be it the game HUD, decorative bits on ships or buildings, or even barbed wire fences meant to slow down invading ground forces are automatically made into obstacles players are unable to fly over. You can see this same issue in jojoisjo's first-person point-and-click adventure game 4, another game where everything has to be drawn from fake walls, bringing with it a huge hit to ZZT's already quite limited graphical fidelity.

In 4, jojoisjo adamantly refused to use objects beyond the bare minimum of one per object the player can interact with. Agent Orange is willing to make the compromise, a trade that feels necessary in order for the game's many targets to be readable as more than smears of color on the ground and to create contrast to delineate something being at surface level or above it.

The nice thing about these little details in the objects is that it's very clear to players that they won't be able to go over such things. If anything, I wouldn't have minded greater use of them as several missions incorporate walls that looks like they can be flown over. While it might not make sense for a plane to hit a radar dish on the ground, it's immediately obvious to ZZTers that these things have to be avoided at all costs.

We Have Always Been At War With "The Enemy"

Story-wise, the game is kept light and very unspecific. This is a military operation, and Agent Orange thinks better than to slap on the names of some real world countries to place at odds with one another. This does make the story a little less interesting than it could have been, as there's no establishing of the enemy's goals, who your squadron is flying for, or what the stakes are should your mission fail. All the same, I don't think even making up some fictional nationals would have done anything for the story that we've all seen a hundred times before. Make up some fictitious countries where one is so comically evil that nobody will question the bombing campaign and you've got yourself a GI Joe I guess. It ain't Kojima, that's for sure[2].

So while the blankest slate certainly won't get awkward in the future of geopolitics, the conflict here is as generic as it gets short of naming the combatants "Us" and "Them".

To some degree this hurts any hope for a deeper story. The conflict's specifics are danced around, though the mission descriptions provide some insight into what you are bombing and why. The story, little as it is, does progress throughout the game's missions, telling of an island invasion to stop the enemy from work on developing biological weaponry. There's no moral ambiguity here. You are the good guys. They are the bad guys.

While sparse in details, there's still some semblance that this operation is at least a series of events. The game's first mission has players proving their capability by flying over a small island just offshore from the main setting of the game. Taking out a small refueling base and observation outpost is intended to prevent the enemy from learning of the approaching force before they arrive.

A lot of the missions operate under the logic of "if we blow this up, they won't be able to sound the alarm". Given how long I was taking and how many bombs I was wasting in most missions, it's kind of a miracle that the entire island didn't mobilize to destroy me. For more skilled pilots than myself, it still stretches disbelief a bit. One can only cause so many explosions before somebody picks up a phone. If the enemy is this inept, then surely the people of ??? (good) will prevail over ??? (bad).

I tease of course. We're playing a video game after all, so one bomber is going to accomplish everything with no support against an entire island filled with enemy planes and cannons that incapable of bringing it down. If anything, it made me nostalgic, reminding me of playing Air Combat on the PlayStation, which shares the briefing and mission structure in 587 Squadron as well as having its missions of "here are the targets, shoot them until they stop existing". It was a nice feeling to revisit, and I was definitely reading the briefings with the odd voice of the PlayStation game.

Just as with Air Combat, the story isn't what you're here for. You're here to blow shit up, and that's what you'll do.

The Heroic Exploits of 587 Squadron

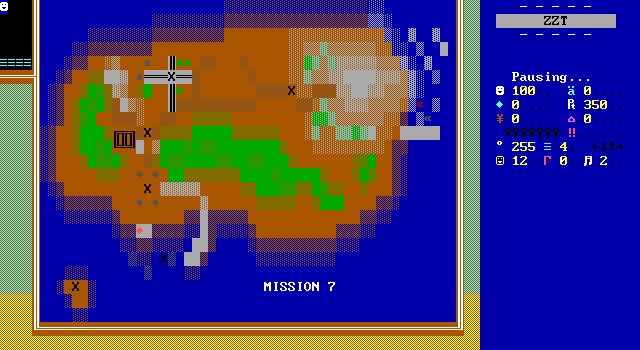

Agent Orange succeeds at making the game's missions feel more involved than just turning red fakes into brown. Each mission is pre-pended with a briefing depicting where on the island you'll be flying, what needs to be destroyed, why it needs to be destroyed, and what kind of resistance to keep an eye out for. Obstacles range from simple spinning guns as anti-aircraft guns, cannons which take advantage of a custom #WALK vector to shoot diagonally, and enemy fighter jets out on patrol.

The game makes good use of its war themeing, coming up with purposes for for each target and making sure that just because the guns shooting you are going to be single objects on the ground, that doesn't mean they can't be part of something larger. You get a real sense that your enemies are a genuine force and could potentially be a real threat if their vague plans can be realized. With ten missions to get through, you'll come to appreciate the cohesiveness of it all. Never does the game feel like a simple timing mini-game. It always feels like you're working towards a tangible goal instead.

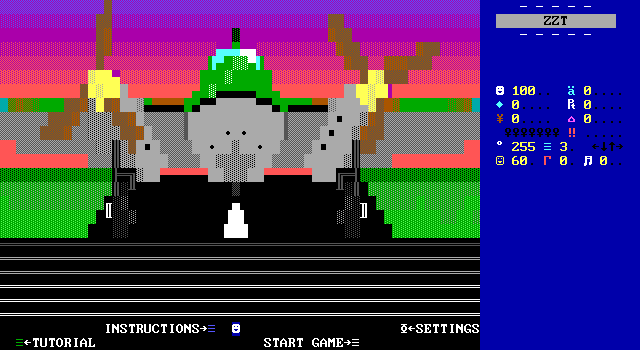

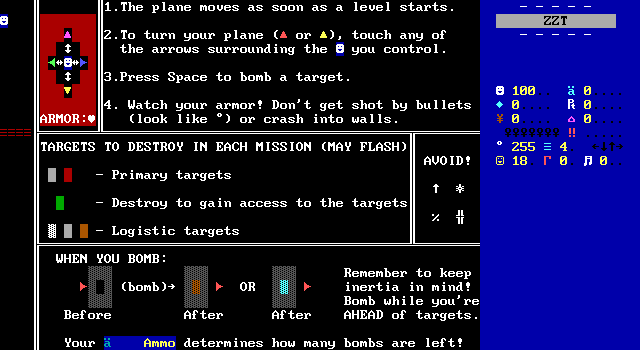

You aren't thrown into this war zone without proper training. The game comes complete with an instruction screen. It's nicely arranged, providing info on controls, targets, highlighting threats, and making sure to concisely explain the bombing mechanics.

As a jam game, this one's initial audience would inevitably be folks new to ZZT, so I appreciate the emphasis placed on the fact that you're controlling the player and not actually your plane. Having the player here get to move around in a small corner of the screen hopefully makes it more clear to players that this kind of gameplay is something Agent Orange is bolting onto ZZT, and not the default gameplay.

Even if those players have no idea what the challenges are of making something like 587 Squadron, they'll at least be more inclined to realize that something is being done outside the norm for ZZT. At least in the sense that the game certainly isn't a purple key collecting adventure.

A tutorial board also gives players an opportunity to fly in comparative safety to the main game. This board presents a few targets that can be approached from a safe angle to let players practice their bomb timing while being close enough to the immobile obstacles to teach the lesson of thinking about how to navigate away from threats after going for a target.

Most of the board is kept empty letting both newcomer and veteran ZZTer alike adjust to the specifics of how the plane handles in this game.

Your speed is also set to normal here, allowing you to decide if you need the decreased speed of the game's easy mode or not without just guessing before starting play. Some way of allowing the speed to be toggled mid-tutorial may have been useful in giving players experience with both speeds, but this is still a step up from ZZT games that have players make decisions before having any clue of what they can handle.

The first mission is as kind as they ever will be. Enemy defenses are focused around spinning guns that were kindly placed by Agent Orange in sub-optimal positions. This makes it easy to approach your target with little resistance.

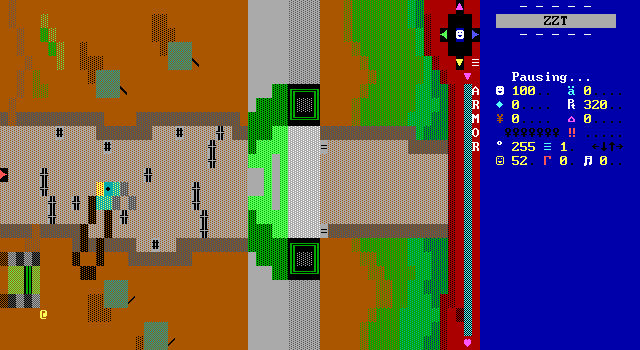

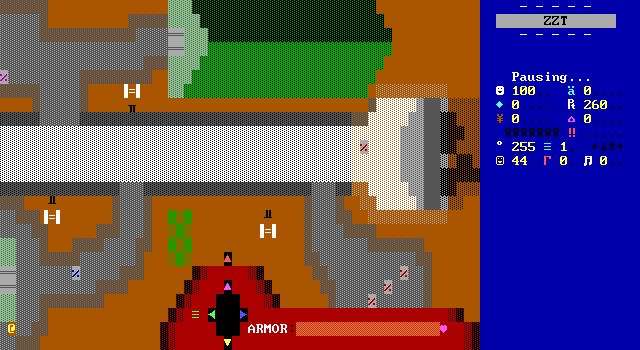

The third mission introduces the concept of preliminary targets that need to be destroyed to open up access to the main objective.

It's a bit silly, having some sort of barrier surrounding targets that can keep a plane out, something that might feel more suited to a science-fiction force field, but it allows for more dynamic feeling missions. Besides, your plane has by now surely crashed into something that would only be hitable at dangerously low altitudes.

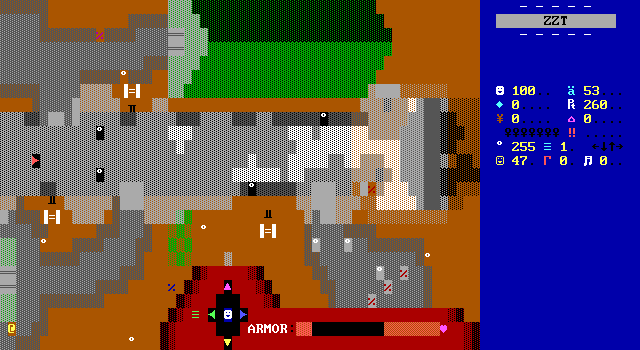

The preliminary targets serve to divide missions into two halves. In their most basic implementation, taking out these green targets changes some line walls to fakes. In more complex scenarios, you can be surprised by more guns suddenly appearing, making a seemingly defenseless target suddenly transform in a weapon of destruction.

The effects the game uses are fairly limited, with little animation (well, your plane crashing is pretty good), so most of the game's detail relies on the imagination. With objects flying randomly around the boards and bullets taking up all kinds of space, more complicated animations probably wouldn't fare to well, easily tripping over obstacles themselves leading to the same kind of graphic desyncs in early shooters than the bomb-dropping gameplay alleviates.

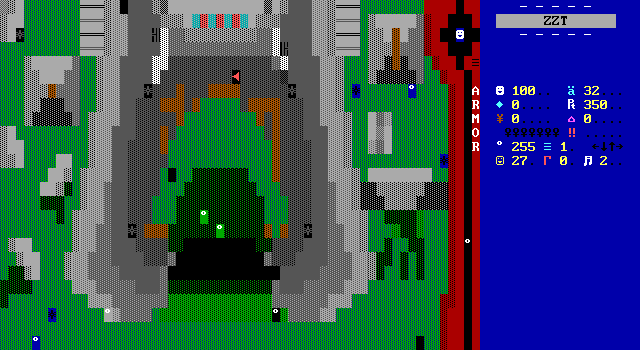

Mission four stands out both because it does a great job of suggesting height, as you fly through a far more constrained stretch of a canyon built from multiple levels of rock and because it has a big finale. In most missions, you blow up the targets and not a whole lot more happens on the board, but upon finishing this one, players are rewarded with the canyon giving way to a landslide, done by having various slimes suddenly appear in the walls that burst forth and cover the ground below, transforming a key route for enemy transit into a pile of dirt.

The game's fifth mission experiments with a much larger target and special bombs to compensate. This time your job is to just obliterate an enemy runway. Blinking red fakes are instead replaced with a clean white lest a third of the screen be flashing at all times. For this one mission you're given cluster bombs which rather than explode a single tile, cover a wider area by dropping a slime that's allowed to spread for a bit before turning its residue into fake walls.

There's another path Agent Orange could have taken where this was the main engine for 587 Bomber, and despite it sounding more appealing (I was certainly excited for the mission), it's perhaps for the best that this was a one-off. The allure after a few missions of high-precision strikes to be able to just go wild and rain explosions from above makes it initially feel freeing.

It's a feeling that doesn't last, as once you get down to the last few bits, you're forced to go back to precise bomb drops. When you miss a target in other missions, it feels like your mistake, but with the random spread of the slimes here, you can feel at their mercy as to whether or not a specific tile gets covered. This can get even worse when enemy shots get in the way.

Still, as a one-off, it's a welcome change of pace. The issues with this mission aren't really something you can blame Agent Orange for, as ZZT has no sane way to count how many of a tile are on the board[3]. Given the time constraints to create this game for a jam, and the fact that it's not actually all that different from the other missions, it makes sense to keep the stage as it is and focus on what's been demonstrated to work with earlier levels.

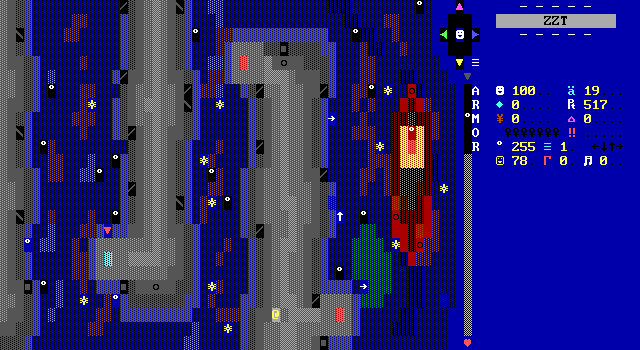

As the game goes on it's easy to feel claustrophobic as the stages become more littered with obstacles. The preliminary targets is an easy way to restrict where players can go, yet whether or not you're confined, the density of obstacles makes it harder to approach targets even without any bullets on screen. Getting used to the specific timing required with the small delay when changing direction becomes a necessary skill. With bullets forcing turns to be made even when you don't want to, your health overtakes your bomb supply for most precious resource.

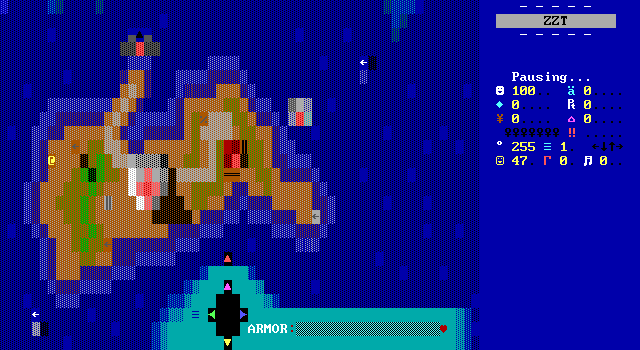

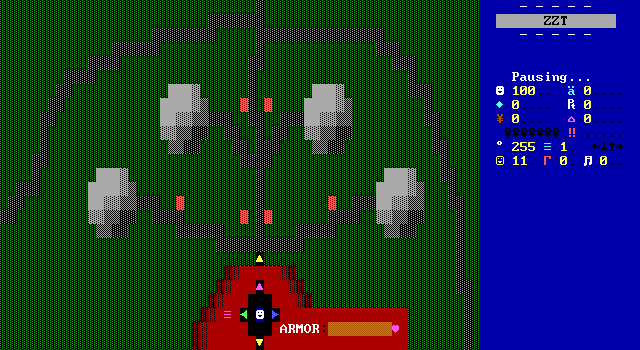

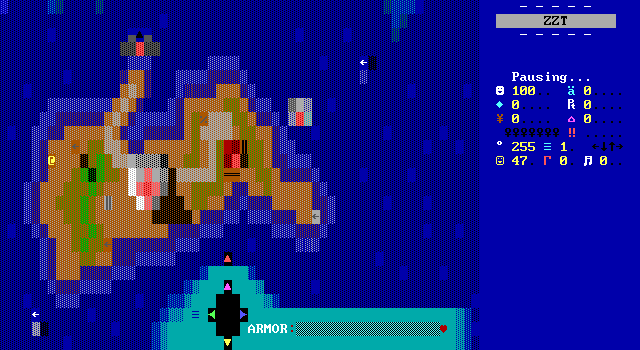

Although, there may be a psychological component to it as well. The game's first five missions use a horizontal layout for the UI, placing the controls and armor meter along the bottom of the screen. The latter half of the game switches to a vertical layout, putting everything against the sidebar. In both orientations, you can safely absorb nineteen shots. However, as tiles are nearly twice as tall as they are wide (well, in MS-DOS ZZT anyway) the gauge appears to drain a lot faster when taking an equivalent amount of damage in the vertical layout.

I promise though, that the difficulty of the game makes staying alive a challenge regardless of perceived health loss. The bar is empty when you crash no matter what!

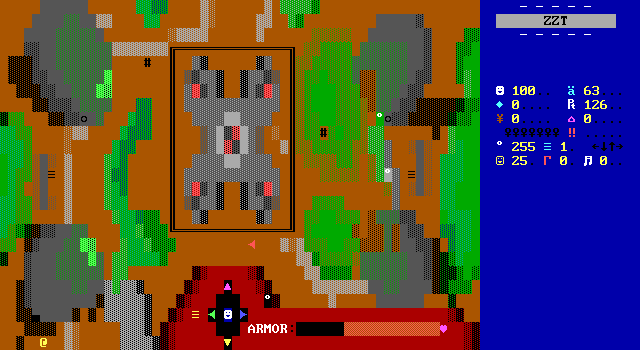

Agent Orange seizes an opportunity afforded by the tighter packing of primary targets. Without the need to draw several small targets all over the place, some more ambitious backgrounds can be drawn. The penultimate mission nine demonstrates this quite nicely. Your plane seems absolutely tiny compared to the massive structure housing your main target: a germ warfare lab. There's a real sense of height on display.

Meanwhile at the top, you get adversarial geometry at its maximum. The building is outlined with text, forcing players to fly through in a C-shape with little room to mistime your turns. It definitely amps up the challenge, though it again really emphasizes that your bomber doesn't really fly over things, just around them.

The ninth mission changes the approach one last time, replacing the open spaces of previous missions with a very linear path to a submarine that's about to cast off and flee the island. This one is more of a matter of survival, with mines ...air mines, littering the path and requiring some tight maneuvers while still hitting a few targets along the way. Realistically, you're still doing what you've always done: avoiding obstacles and bullets while trying to time bomb drops. Yet by restricting movement to a set path it feels like the game is now actively testing your flying skills.

The final mission really commits to it, with your plane being directed to a hidden aircraft carrier off the rocky northern edge of the island. It's part challenge, part victory lap as you have no bombs to drop, just flying down a runway and covering the lone "target" with your plane rather than blowing it up. It's not a free win though, as the rocky terrain here requires the most intense handling of your craft in the entire game, making you zig-zag between crags having to change direction back and forth repeatedly to travel a path where cardinal directions alone won't cut it.

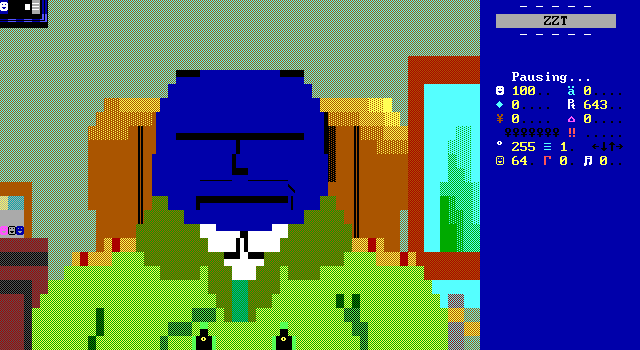

Upon completing your mission, you get one last debriefing from your commanding officer who despite his grumpy appearance has nothing but praise to bestow upon you for a job well done. The ending is adjusted based on the difficultly the game was played at with the player getting a chance to rest before the next mission, or earning a month of leave for their efforts.

And it ends as all good ZZT games do, with a beautiful sunset. See you next mission. If you made it this far that is.

- [1]Everybody who has released an Oktrollberfest entry knows that the weird weighing system of Itch's jams results in some bizarre scores that don't necessarily reflect the quality or overall feelings on the submission! 22nd is probably pretty dang good actually.

- [2]*has not actually played a Hideo Kojima game since Metal Gear Solid for PS1.*

- [3]Red Deviance is a 3.2 world that counts remaining centipedes at the end of a level. This grotesque process involves purposely hitting the stat limit for the board, changing the centipedes into something without stats, and then counting how many statted elements can be placed before attempting to do so doesn't produce any new element. It's slow and wouldn't be much of an experience on a Game Boy Advance system.