A mixture of technical issues when attempting to record a playthrough of Quest for the Time Portal combined with discovering that the game's passage layout is a mess which would require considerable effort to unravel if it was even possible to complete at all led me mashing F5 on the roulette page. It was one of those unproductive days where I had a late start on everything and then had probably an hour and a half of playtime thrown in the garbage that had me desperate to find something I could play. Then I tried The Master 1, which was over in like 10 minutes, during which nothing of note happened.

I was eventually led to The Guardian, not out of my usual love of ZZT RPGs and dungeon crawls, but just as something that looked competent enough that I could actually get through it and have something to say about it. I wound up getting a very lucky break. This game wound up being one that I'm going to be thinking about long after playing.

The author of the game, "Question Mark" wasn't one that I recognized at first. Early on though, I wanted to get a look at the code for the game's combat system and realized that this was the same Question Mark of "Question Mark Team", and my curiosity for the world increased tenfold. The Question Mark Team was a company that until recently I also wouldn't have recognized. Back in August however, I played through Prisoner, an ambitious, psychological horror game that truthfully didn't do a great job of things. I ran into bugs with flags, repeatedly found myself unable to figure out where I should go, and the overall vibe of the game was of somebody trying to make a creepy horror game and just throwing ideas at the wall with no real consideration for what it all means.

Prisoner began with a title screen filled with paranoid-reading text and including neither author nor game title. It's the sort of game that you can tell right away will be something to remember, and it certainly was. People melting into slime, a blatant cover up that the everyone but the protagonist seemed to be in on, gruesome murders with trails of slime, finding your own dead body, and then going back to work and discovering a woman that exists in two places simultaneously with no knowledge that she's somehow doing so. It hooked me now, and it probably would have been an obsession of mine had I caught it when it was released back in 2001.

The Guardian meanwhile shares Prisoner's ability to instill a sense of unease, evoke the supernatural, and get players suspecting that there's no way Question Mark has any hope of coming with an ending that will leave you satisfied. (Lord knows Prisoner didn't.)

My expectations were hard to pin down. Prisoner had more bark than bite, showing a lot of ambition but really only making players run around in circles. A game that's difficult to genuinely recommend afterwards that I couldn't put down while I was playing it.

With Guardian, Question Mark again excels at getting players invested, this time with a focus on deciphering clues for puzzles and fighting horrifying monsters, yet once again fails to stick the landing. It's another bizarre experiment that I wished had been a success, especially with how hard Question Mark tried.

False Premise

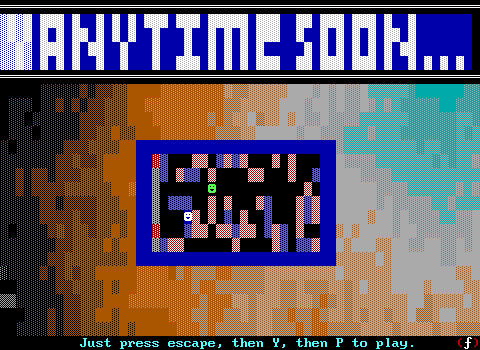

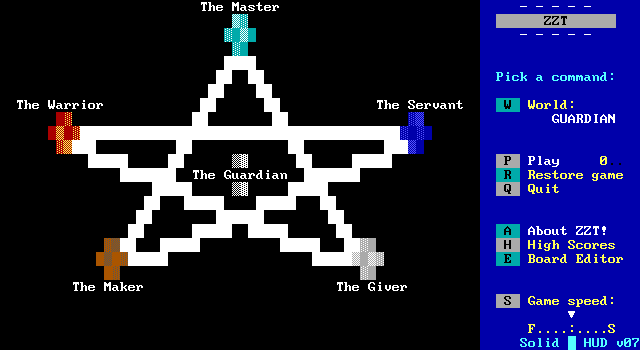

Going into The Guardian, I had no real idea what to expect. Prisoner was just one game, not enough to assume that everything Question Mark was involved would look or play similarly. The title screen is far more typical, and honestly, looked a bit mediocre compared to other games of the era it shared a genre with like DavidN's The Mercenary or coolzx's Dark One's Rising demo. It looked more like something I would have made. That's never a good sign.

A pentagram with crude circles at each point of different color representing some unknown persons, and "The Guardian" itself lying in the center is all you get. Were it not for the name being in the text file and database info, I don't even know that I'd recognize it specifically as the game's title. It's not much. Done entirely in blocks and text with no rounding or smoothing via some half-block objects whatsoever.

But you know about not judging books by their covers I'm sure. An uninspiring title screen at worst means an author with room to improve in the visual department. Prisoner showed me that Question Mark's strong suit lay in his ability to create an unsettling atmosphere. There was still so much to see. I couldn't let white solids and low-budget circles keep me away.

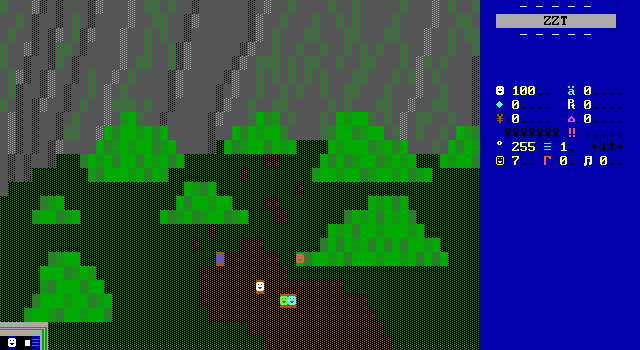

Things begin in a very expected way for a ZZT RPG. A cut-scene plays out to establish the characters and their goals. A group of people traveling walking together come to a stop and decide it's time to rest for the night. One of them asks for a reminder on where they're going, and Question Mark without even having to try immediately establishes what sounds like a pretty cool premise.

Players are Cassius, who appears to be the group's leader. The group are no innocent travelers, but raiders getting into position for their next mark. We get a sampling of their personalities when it's revealed that Theodore does not in fact have a tent for them to sleep in. Neither does Simon.

...As an aside please don't have two characters named Simon and Theodore. It will lead to people like me having expectations of high-pitched covers of pop music.

Cassius isn't all that bothered though. I suppose as long as the weather is pleasant enough it won't matter much. Everyone settles in for the night, including Mattius and Oliver, who weren't responsible for packing a tent.

Were this the beginning of an RPG with your crew rolling into towns, fighting off their protectors, and taking all the good stuff for yourself in an endless quest for more wealth and power, I'd totally be down to play it. Even in ZZT where the there are experiments abound, rarely does one actually get to take on the role of the villain. I was immediately on board with what Question Mark seemed to be offering.

...None of Cassius's crew will ever be seen again.

Nightmare Fan Game

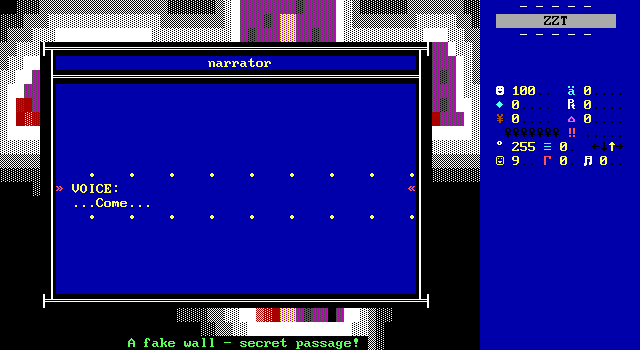

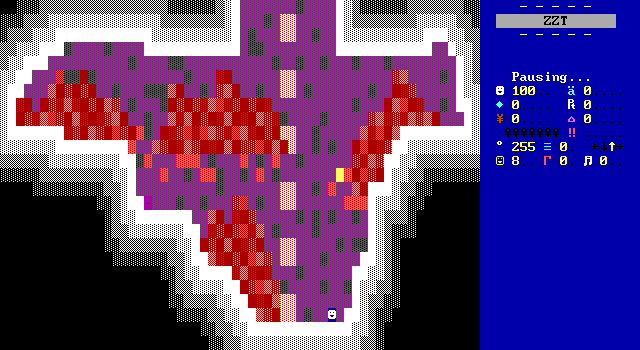

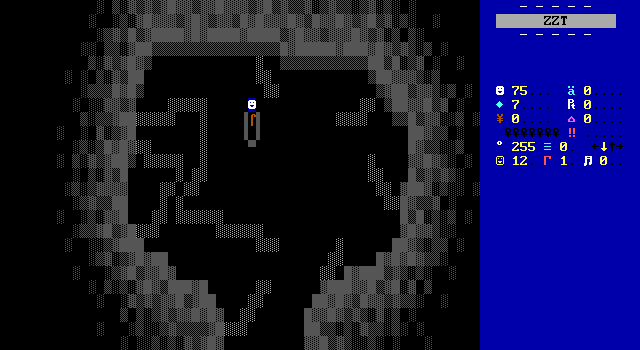

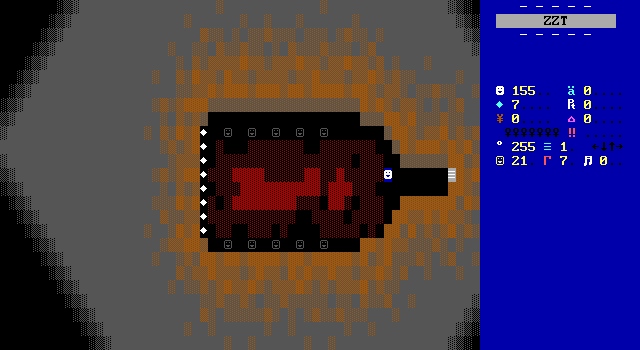

The gameplay begins not with anything related to Cassius's raiding party, but rather a surreal dream sequence where a strange voice calls out to Cassius to free him.

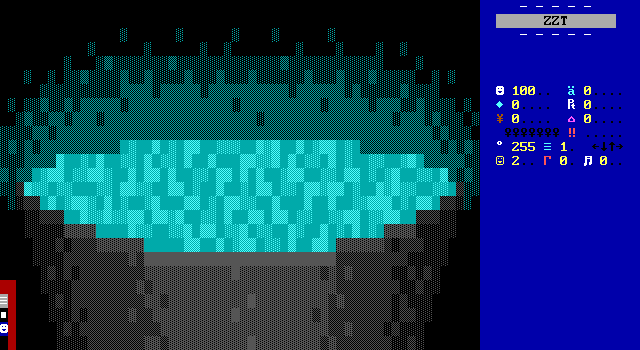

The dreamscape is arranged into a cross shape with a sealed cauldron filled with an unknown substance in the center. There's no explicit guidance on what players need to do on these screens, leaving it up to them to realize that they all contain a puzzle to be solved.

Credit where it's due, Question Mark's four puzzles all manage to be uncommon or wholly original. Don't expect Sokoban, slider pushing, or trivia here. Instead you get dodging shifting mines, avoiding being shoved, carefully navigating spikes, and crossing a continually flooding room.

The player begins in the room with the mines, a perpetually raging fire with moving bits that explode if Cassius lingers next to them for more than a cycle. These explosions not only hurt Cassius, but leave a permanent scar on the board that limits further movement. Players need to tread carefully to maintain their health as well as to ensure that they can still reach the exit.

Realistically, health is the more pressing concern as the mines are fairly spread out. Probably for the best as the last thing you'd want is to actually force players to have to restart the game due to a mine's random inopportune movement.

Reaching the goal, Cassius will receive a key made of fire.

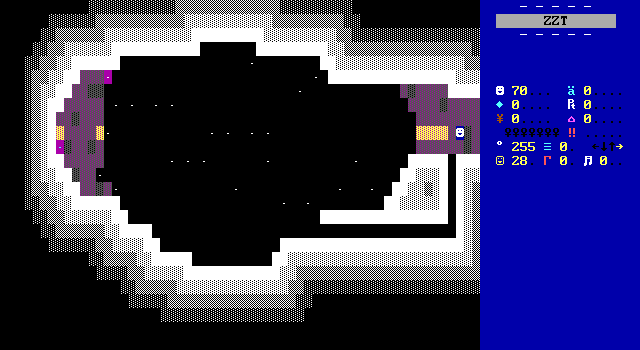

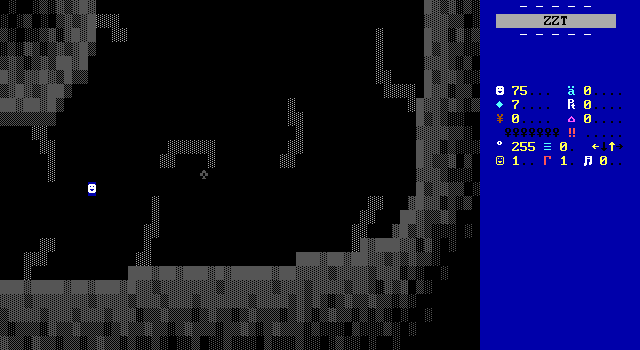

To the west lies the most impressive puzzle. The small dots here represent the wind which will blow whenever the play aligns themselves with one. John Thyer's Atop The Witch's Tower had a torture chamber where spikes would extend when blocked in the direction they pointed, requiring players to find a way to make it to a goal while also successfully bringing a boulder with them. Question Mark predates and differentiates by having the wind based on player alignment, which makes it much more challenging to chart your path, turning it into a slow process. Getting pushed by wind often snowballs into being knocked all the way back to the start, so every step is crucial.

And unlike the spikes that clearly point in the direction they'll move, the wind blows in an arbitrary direction per point. Stepping in front of one can be a blind guess, hoping that you won't be blown away. However, most sources of wind can be safely observed from earlier in the room where they don't yet have the range to push you away. Paying close attention to what direction upcoming tiles blow in is necessary to make it through safely.

It's a very original puzzle design, bolstering the strong start to The Guardian, giving players the confidence that they're playing a game made by someone who not only knows what they're doing, but has a few ideas up their sleeve.

This time, the goal is a key made of smoke.

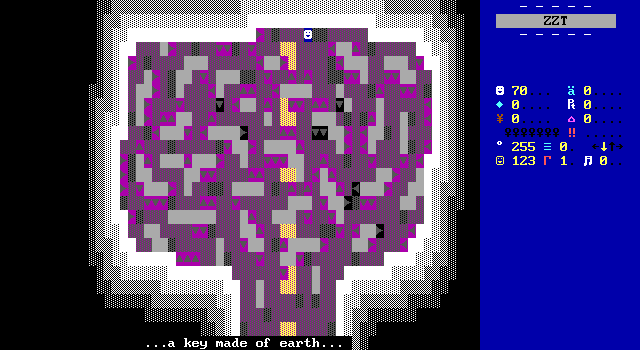

This compliments of the wind puzzle's design can't be said of the path to the earthen key. This one is little more than a maze with spikes that hurt the player if they should misstep and touch them. It's over as quickly as it begins. Since there isn't any incentive for players to move quickly through the maze, a little bit of patience is all it takes to get the key unscathed.

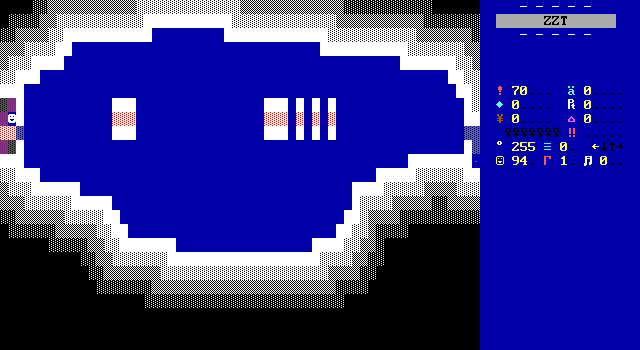

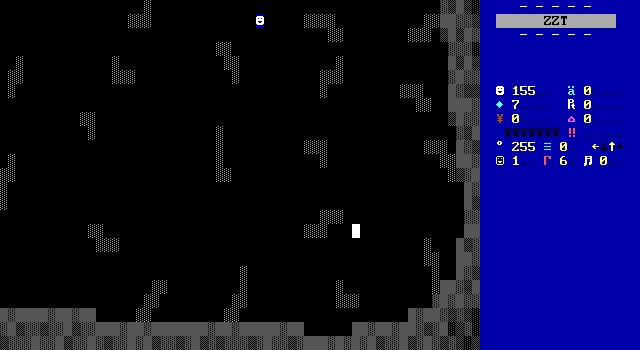

The final puzzle is another instance of something quite different from the norm. A small lake fills the room with the final key at the other side. The tide repeatedly cycles between low and high. When low, a path appears for players to take. When high, being surrounded by water will wash Cassius away to the starting point, taking ten health in the process.

A few little islands prevent portions of the path from being submerged even during high tide. The puzzle tests Cassius's reflexes in making it across quickly enough to reach the next safe location, and eventually the key itself. It's surprisingly tight on timing, to the point where I genuinely thought it was bugged during my playthrough, but returning to it later I discovered you can be quick enough. It also suffers a bit from the path always amounting to just holding right up until the final stretch where extra finesse is needed to turn into the key chamber. A more complex route, with more generous timing, might make this one a welcome challenge.

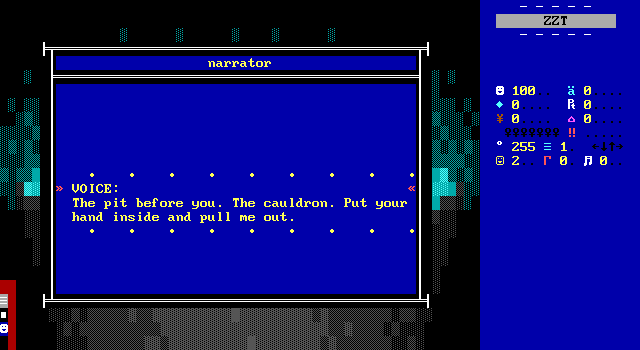

Once all the keys have been used, Cassius tells the voice that they are now free, yet it still demands to be released, louder, and more angrily, unnerving Cassius who now seems to realize he has no idea who he is freeing, or more importantly why he is freeing them.

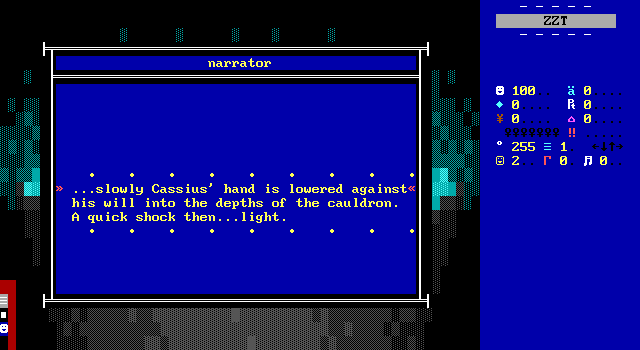

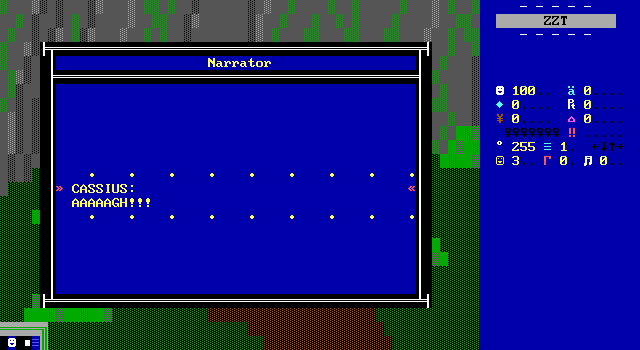

A new cutscene ensues, with the voice of the still demanding to be freed, and Cassius now clearly scared of what will happen when he does. Despite his resistance, he is unable to refuse the voice's commands, reaching his hand into the cauldron and pulling something out with a flash of light before the dream ends and he awakens alone.

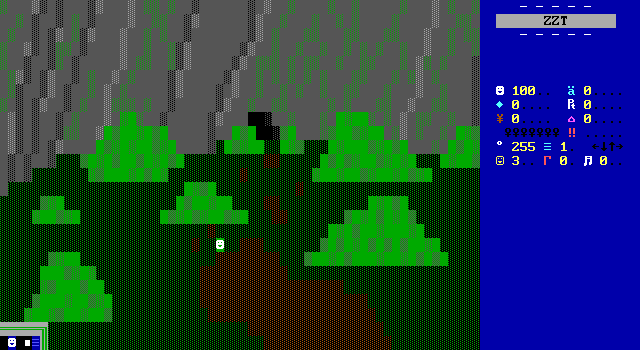

His friends have vanished, and the only place they could have gone would seem to be into the cave that was hidden behind the vegetation earlier...

My Idea Happened!

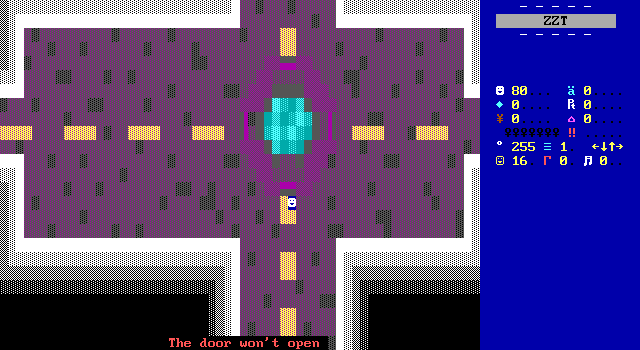

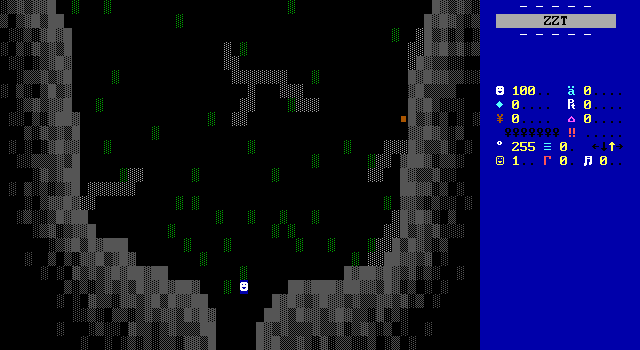

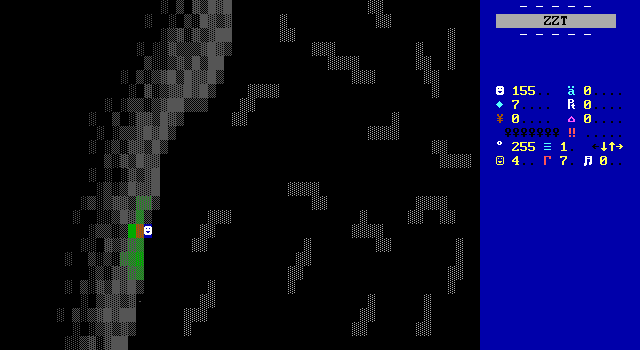

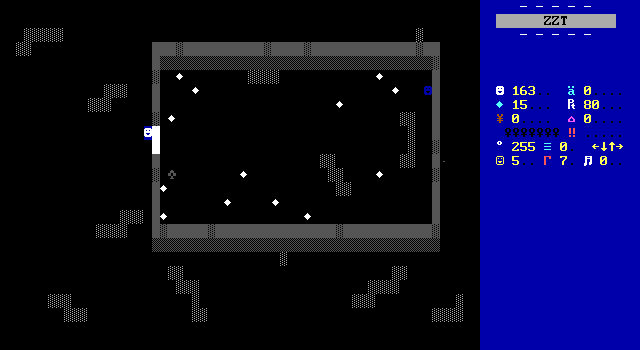

Entering the cave brings players into a series of wide cavernous regions, the first of which is abruptly stopped by a large door with paths branching off to the sides. It's notably empty, a surprisingly effective tool at creating suspense in games like this. At least, as long as it doesn't remain empty for so long as to become repetitive.

The silence as Cassius explores the cave won't last too long. After a board or two depending on what path he follows, he'll run into one of a few different creatures that live in these caverns.

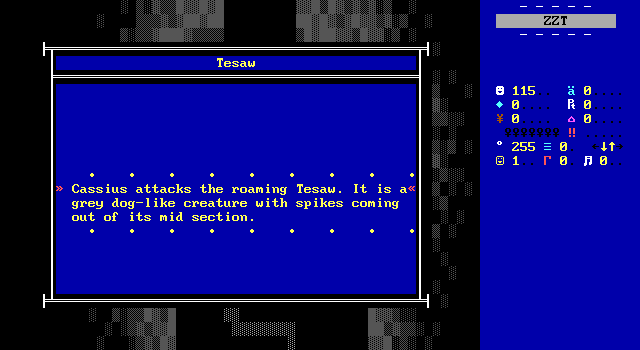

For its bestiary, Question Mark creates a few new creatures from whole cloth, with names like Zeun, Tesaw, and Mayta. These are some strange names for strange beasts, but there's much more to them than their names as Question Mark has come up with a combat system that I believe he may have been the first to implement. Touching an enemy will initiate combat which is done entirely via the message window.

That alone makes for an uncommon approach to fighting, but not a unique one. Typically, games that go for the self-contained RPG battle provide the usual basic list of actions: attacking, defending, using items, or casting spells, which are tuned to the needs of the game being created. You can see this in games like Da Hood or A Dwarvish-Mead Dream. Though it was never really popular due to the various limitations of the format.

Potential pitfalls include players struggling to save during combat, which when low on health can be the only way to get through a fight. They may find themselves in a really nasty situation if a second enemy reaches the player during combat with another as these engines usually use a spare counter like torches to hold enemy HP. If two enemies attack, their HP pool combines and they'll be taking two attacks per round until reducing that number to zero and defeating both enemies at once.

They also lack the visual flair usually associated with ZZT RPGs. Historically, they were engines used to demonstrate mastery of ZZT-OOP, and a skilled author would make sure to include all kinds of bells and whistles with characters moving running to one another to attack, swords and axes swinging when they get there, and extensive use of invisible walls to create effects for spells. None of these can happen in ZZT's message windows, making for a much more dull experience of seeing whose health reaches zero first.

Even games like Defender of Castle Sin could at least create large artwork of the enemy being fought. ZZT's windows meanwhile are stuck with two colors, with only one available per line, and always start with the first line in the middle, requiring scrolling to see more than a few lines of drawn art or anything else.

The repeated scrolling alone is enough for me to not be a fan these days, though I had more patience in the past.

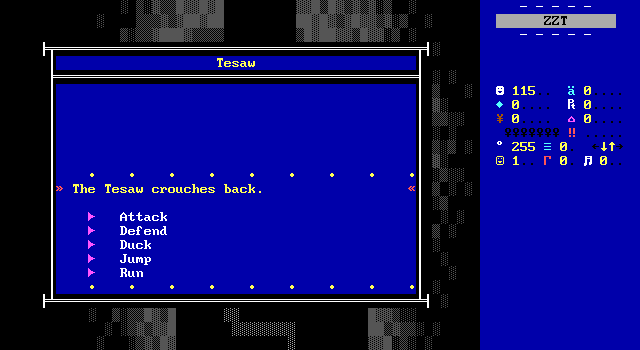

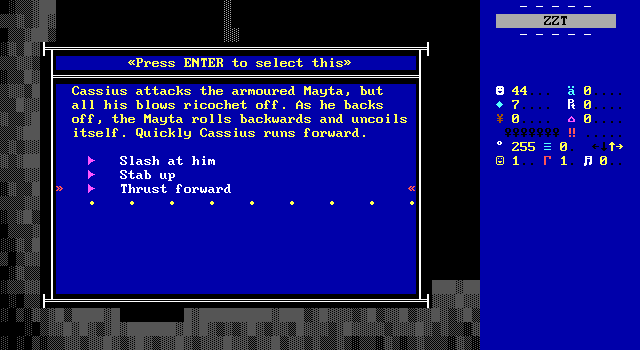

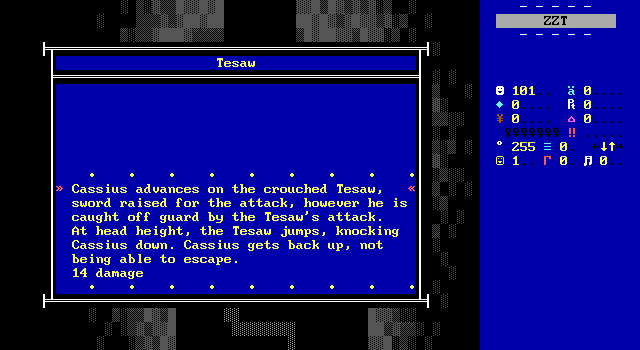

Question Mark takes a more novel approach which in some ways is brilliant, and in others, just does not work as hoped. You still get your list of actions, but the list offers far more choices than the norm. Every monster is given a description of what it's doing at this moment. Enemies may bare their fangs, stand on hind legs, or get into position to pounce on unsuspecting prey. Players then choose how Cassius reacts. Options are instead to attack, defend, duck, jump, or run. The combatants then clash, with your choice determining how well you fare.

There are moments where it works spectacularly well. Seeing a foe begin to leap and ducking out of the way will send the enemy crashing backwards, giving Cassius a great opportunity to strike back. The tortoise-like Mayta needs to have its non-armored underbelly exposed before it can really be harmed. Players need to really consider what choice they make based on the hints given in the monster and combat descriptions. Additional complexity is sometimes added by having in-between phases where possible actions are changed for the specific moment rather than the default set, providing more opportunities to experiment, and hopefully survive.

And to top it all off, these descriptions are pretty darn good. I don't think I've ever been able to so clearly imagine the details of a fight. Question Mark goes into great detail without producing a wall of text, describing shrieks of pain from animal and Cassius alike. There's mention of feeling light headed after being knocked to to the ground, and clangs of sword striking armor.

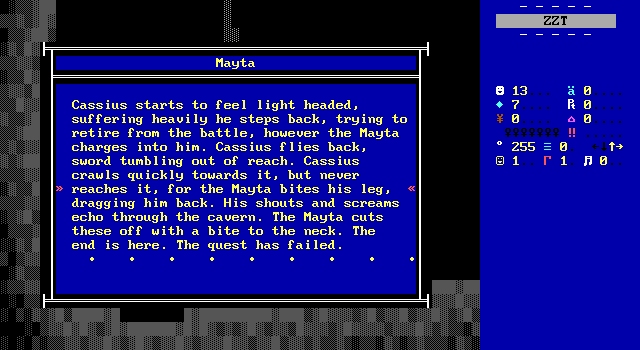

Fatal blows have unique messages of Cassius being no longer able to defend himself, being bit and dragged the beasts until they happen to go for the neck. It's simply brutal, a natural fit for the game's dark atmosphere.

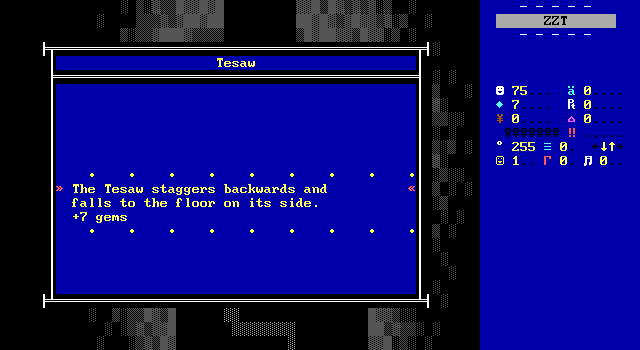

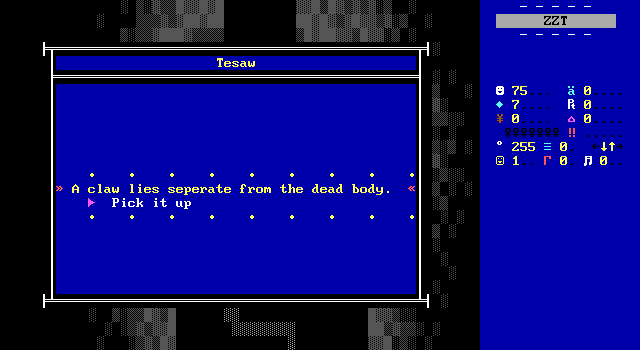

Defeated enemies drop items that Cassius can use to enhance his weapons provided he can find the magically enchanted spot to do so as well as gems used to purchase healing and hints from the game's lone NPC.

Each enemy has the same actions, buts requires different techniques to defeat. It is light years ahead of the sleep-inducing paradigms of "Attack/Defend" or "Stab/Slash" that plague far too many of ZZT's RPGs. It such a breath of fresh air. It feels so different, and so lovingly designed, making the combat the game's finest moment by far.

Still, all choices come with compromise, and Question Mark's combat is not immune to this. The large amounts of text add up quickly. Individual enemies range from seven to ten thousand bytes out of twenty. Because of this, boards only ever have a single enemy which can very easily be avoided rather than fought. Given the very open spaces the game takes place in, you can avoid engagements with minimal effort, especially if you realize that these enemies only attack if touched rather than coming into contact with the player.

The text also leads to trouble thanks to the considerable health pool enemies have. This number isn't visible, Question Mark instead just zaps labels for health (and avoids the risk of a strong attack on a near-dead enemy leading to zapping the last label by including a healthy buffer of extras). For example, the Zeun, a humanoid creature with gray skin that fights with a bone club, has thirty-six hit points. The damage Cassius can inflict on this monster can be as low as three or as high as seven with the standard sword. That's quite a number of attacks to be made to defeat even a single enemy, and it's not even a die roll as the damage dealt is based on Cassius's attack and the monster's current state. Sometimes you just can't inflict damage at all and have to focus entirely on dodging blows until the enemy makes itself vulnerable.

Question mark tries to mitigate this somewhat with bonus damage that can be inflicted with weapon upgrades, but the upgrade system requires a lot of combat to be able to even attempt. The items like claws and scaled dropped by defeated enemies need to be applied in groups of four in specific orders to generate specific weapons. You can purchase some hints for the recipes, but those aren't available until the final area of the game, and depending on when players acquire them, they might not be have any reason to take advantage of it at all. In my playthrough I didn't buy the appropriate hint, didn't find the appropriate upgrade point, didn't find all the necessary items, and got through just fine by avoiding enemies after a point.

The slow pace of the fights are made worse by the fact that there aren't that many scenarios to begin with. Enemies have five actions they can try to perform, determined by checking if they're blocked in a random direction. If they are, they'll jump to a label, otherwise they'll try again with a different label for success. It's not exactly a clean distribution, but in practice I was seeing enough variety in the attacks to be impressed at first.

It doesn't last though. Thanks to the considerable health of most enemies, the first fight with a new kind of enemy will likely have players see everything there is to see, and once you find an attack that works well, there's little reason to pick anything else. You'll see the same well-written descriptions of combat again and again until the enemy is finally killed. It's slow, and quickly gets tedious. Why fight a second of the same enemy when you've already seen everything it can do? Especially when you'll probably flounder at some point, mis-remembering if you were supposed to defend or duck when Monster X starts growling, and taking damage for it that could be avoided simply by not fighting.

An option to run is included as well, which is also based on the enemy's current action, so you either do so and get away every time from that state, or don't and in some cases take an extra attack in the process. The format here is admirable, but perhaps best saved for boss fights rather than mundane random enemies meant to be fought repeatedly. The combat inevitably feels like a waste of time even if it makes one hell of a first impression.

What is here is still really impressive. (The first time at least.) The repetition and lack of incentives to bother fighting hold the engine back from its potential. Still, I was very pleased to actually see it. It brought back a memory of the Closer Look for Pokémon Twin Pak! of all games, where I tossed around the idea that the game could have benefited from leaning into the creative thinking seen in the Pokémon anime, turning fights into a puzzle of learning how to handle attacks and find ways to deal damage rather than that game's approach of "You didn't pick water gun so you died".

For a better comparison, the second file of John W. Wells' Evil Sorcerers' Party features a puzzle-fight with a Gaunt Thing, having players select from simple magic tricks to find a way to survive for long enough that they can be rescued. ESP wouldn't be released until the next year, so at the time of The Guardian's release I'm unaware of any other game that had ever tried something like this. It's an experiment that gets very close to being something truly wonderful, and I suspect with some tweaking both to the engine as well as the world that accompanies it, that this kind of fighting probably can be done rather well. Here, the novelty is enough to get it 90% of the way there, and the fact that you don't actually need to fight anything makes it great to check out and then ditch once you've exhausted all the options in combat.

Puzzles In The Dark

The monsters in the cave aren't intended to be the focus, even if they're the only real threat to Cassius making it out alive. Cassius's priority is to find his friends, which means finding a way past a massive wooden door, the only place left they could be. From this point forward, The Guardian becomes a series of puzzles to solve while dodging these enemies. The first of which being how to open the door, which is disappointingly a problem whose solution amounts to getting lucky.

What players need to do is throw four switches spread across twenty(!) boards. Each switch pulls on a chain, and when all of them have been pulled, the massive door will open. It's a simple way to make player visit every screen before continuing and in theory provide a steady sense of progress as you reach each one.

Question Mark makes a very questionable decision here that marks the end of my honeymoon with this game. These switches need to be pulled in a specific order. If players pick the wrong switch, it won't stay put, reverting to its original position to indicate that nothing happened. This changes the exploration process from venturing through the caves as you please, making sure to visit each location, to instead constantly going through multiple boards in a row and accomplishing nothing other than wasting time. Given the size of these caverns, which are almost entirely empty, there's nothing to hold the player's interest as they walk through a branch of the cavern for the fourth time hoping this time it's the right lever to pull. In those screens that have enemies you're given a wide enough berth to dodge them every time you pass through, and if you fight instead, then the room is likely devoid of anything to interact with.

Making things even worse, choosing an incorrect switch will reset every lever. There's no indication this happens or hint that anything is more amiss than the wrong lever having been pulled. From what I can tell, there aren't any hints at which lever comes when, turning the entire thing into a lengthy guessing game.

Playing under SolidHUD, I had the luxury of being able to check my flags as needed. Under vanilla ZZT, the only kind available when The Guardian was released, you would eventually find the first lever, then pull an incorrect one, and have no reason to consider revisiting a board that should have an already pulled lever on it. You'd almost certainly explore the entire cave system and make no progress first.

For a number of players (myself included), I think they'd sooner assume the puzzle was simply bugged and move on, zapping past the door if Question Mark was lucky, or just play Nightmare again instead to get their fix of puzzles in dream sequences.

Assuming players managed to actually get the door open, Cassius can then continue deeper, still holding out hope that his companions are somehow in there, as there's really nowhere else left they could be as he enters the second part of the caverns. The bigger caverns.

Yeah, the second part of the cavern is one gigantic room that continues the trend of most boards being empty save for a lone enemy on a few screens. It's a wide open space that's faster to cross at least.

Instead of levers, this time Cassius needs to seek out some candles. Certain locations have various runes written which provide prompts of more runes as possible answers. The candles are the key to deciphering the language. Question Mark again does something unusual, making the side the candle is touched on produce a unique message, necessitating touching them all four times. If you're used to objects not caring where they're touched, or at least communicating so in the rare instances they do, it's easy to not take the hint in the message of "words are engraved on this side" as an invitation to check the other three as well.

Once you do, it's immediately clear that the candles are a Rosetta stone, each with two phrases in English and the equivalent in runes on the opposite sides. While I've still got my notes, here's the key:

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ° | ⁿ | └ | ± | ß | ú | « | Æ | ■ | · |

| K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T |

| ∞ | σ | α | á | ª | í | ñ | ─ | É | Θ |

| U | V | W | X | Y | Z | ||||

| ╗ | ∙ | ~ | ó | æ | |||||

Question Mark covers his bases, including enough words to cover every letter except Z. Players that realize what's going on likely won't need to find every last candle, a much needed departure from the levers seen earlier. Once you have good grasp of the cipher, context clues make it easy to fill in any other necessary letters when you begin your translations. Be sure to have a piece of paper or text editor handy.

The runes are used in two puzzles. On the west edge of the cavern, one of the only bits of color underground can be seen. A giant tree trunk covered in vines has a series of faded runes carved into it, with a prompt of nine possible words carved into the adjacent stone wall. A rusty knife stuck in the tree draws Cassius's hand, guiding him to carve in a sentence of his own made from the words.

Arranging the words into the sentence which when translated reads "I SCREAM INTO THE DARKNESS, NIGHTMARE FOLLOWS MY TRAIL." will reveal a passage into the rock.

The second use of the runes is found in the final room of the game. Players pass the much smaller door which is initially out of reach as they transition from the the big door into the bigger cavern making it an obvious point of interest once they're able to explore freely once more.

As far as final rooms go, it's rather drab. A slab covered in swirling runes blocks the exit. Each time Cassius touches them the runes rearrange themselves. The fancy imagery is a nice dressing up what amounts to a multiple-choice quiz where both question and answer need translation.

Once translated, they're easily answered. "These caves have how many creatures", "There are four candles" (True or false ...or die ...or dogs), and lastly "You can see magic in:".

It's better than the ZZT/MZX trivia recently seen in Savage Isle at least.

Nobody's going to get too excited over a substitution cipher, especially if they've already used that same cipher at the tree trunk. The game's final puzzles winds up being much weaker than the more interesting ideas explored during the dream sequence. The whole game kind of slows down even more around here, with no new enemies to fight, and more of the same running through big empty rooms. Fortunately, while the cipher is the key to heading to the game's ending, the passage behind the tree does lead to something far more engaging.

At least, it does if you're actually thorough in really taking in all the hints provided. Upon entering, it doesn't look like much. There are some gems to collect, a resource that previously has only been awarded for victory in combat. These gems can be used to purchase hints and healing from the game's lone NPC, still yet to be discovered. Except if you're capable of getting into this room, then the only remaining puzzle is the trivia that uses the same logic as here, so hints are a bit moot and for the thousandth time you can just ignore every enemy.

The only other objects of interest are some rows of armor with plaques that list strange names, if they're even meant to be names. "Parce Awner West Night" may be a mouthful, but at least it's not as bad as it is for the poor child named "Bartin Iyn Sort Holeo Orka Port". The odd captions make them a prime target to study for a future puzzle, and it didn't take long for me to realize that taking the first letters of the names listed would spell out the names of chess pieces.

What I didn't do initially was put two and two together with the text carved into the candles. One of which has the messages "More may be found" and "Past the queen". Investigating the walls by Quell Uence Ether Eel Norman reveals a hidden passageway with a number of journal entries carved into the walls and an exit that has caved in.

The War That Wasn't

The chronicles carved into the walls in this small room hint at the greater plot of the game, and I'm baffled that Question Mark opted to hide them behind an optional puzzle when they're such a good hook for what Cassius might be getting himself into even if he makes it out of the caverns alive. They paint an intriguing story of the game's world that's easy to miss completely, really changing any theories as to what might come next..

According to the carvings, the cavern was discovered during the reign of a previous king of Martor (the city Cassius planned to raid). It was decreed that they would be sealed off, only to be used in times of peril. The statues were placed in the room and the door sealed.

Years(?) later, Martor found itself under siege by the kingdom of Aidor. The king ordered the caverns opened once more, planning to mine exits from within the existing caverns in order to flank the enemy army. After some difficulty getting past the beasts down below, the plan is successful, and the Aidorian army is forced to retreat. The people of Martor still fear that they will return again, and so the king decides to press the advantage, sending his army on the offensive to invade Aidor before they have a chance to regroup and strike again.

The counterattack begins with a number of successes, leading to the capture of several towns. Progress begins to slow as the army heads further north. They find that as they travel in that direction, the air becomes fouler, the sun hazy, and dead animals and people can be found rotting on the sides of roads. The army's advances slow due to difficulties with the inexplicably harsh environment, eventually heading back to their homeland. By the time they return only half of their forces survive. And among the survivors, many who have made it back are suffering from sort illness which for some is so severe that they are brought into the caverns to die.

It's pretty metal.

The final entry reveals that Aidor's attacks have stopped completely. Their land is under attack by a new threat, a mysterious cloud that descends on the land known as Naeparm. With no real way to fight it, Aidor is unable do much of anything other than rot and hope that the cloud doesn't continue to spread. The author of the entry fears what might happen should Naeparm reach Martor and how they could possibly hope to defend themselves from it.

The chronicles go on to mention the queen will likely die of age within the next decade and has no heir. Combined with Cassius's original raiding plan, players know the queen is dead. Now they know of a blight which would surely decimate Martor. But if it has, or when it will remains shrouded in mystery.

Lastly, it reveals a combination of items to use to power up a sword. If players defeat one of each enemy, they'll get the ingredients used to magically fuse with their blade. Once more speaking to the lone NPC, they can boost their attack power, though again, by the time they're able to capitalize on this, the game will be all but over. (Though a password system means it could be of use for the next chapter.)

Weird detour to talk about making a cool sword aside, seeing this really grabbed me. What would Cassius find when he reached Martor? How much time has passed since the last message and the queen's death? What happened to Aidor and what has happened since to Martor? These are questions that could have interesting answers. I'd love to see a game about the town dealing with a seemingly unstoppable blight slowly approaching. Cassius and his crew don't seem the type to try and save the world, but who knows where events would take them?

Not to mention, all of this is detached from from his friends' disappearances and the mysteries of the caverns themselves. There are a lot of threads here that are bound to intersect eventually, but when, and how is left to the imagination. I'm a sucker for this, and just like Prisoner, really want to see the sights of such an eerie and unnerving world, even knowing full well that the odds of a good payoff are rather low. Especially now, where I've seen how Prisoner ends, no longer being left entirely in the dark as to what happens when Question Mark tries to deliver an ending.

It's regrettable that the real hook of the game requires so much work to uncover. Being the leader of a group of raiders is novel. Strange dreams and missing companions is a solid stepping off point for a ZZT horror-mystery. A world plagued by Naeparm that players have no idea how far it's spread, how dangerous it is, or if anything can be done to stop it? That's attention grabbing. Question Mark shoves all of this into a first chapter, with a number of directions to take things in. I'd love to know what was planned for this one.

There's a Guy Down There!

As I keep mentioning, there is a single NPC Cassius can meet underground. A room within the larger cavern has a heavy marble door that can only be moved by finding a hidden switch elsewhere. It's not too difficult to find, as there's nothing else on the board it contains aside from the usual silver marks of magic dust on the floor. Really it's a matter of crossing the screen in the first place as the large size of the cavern and candles being places out the edges may keep players from seeing every screen if they aren't focused on methodically mapping the cave.

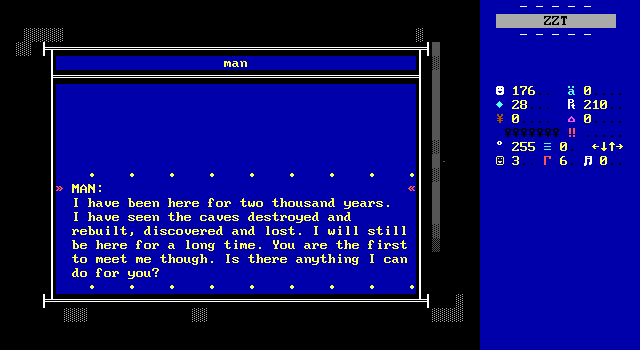

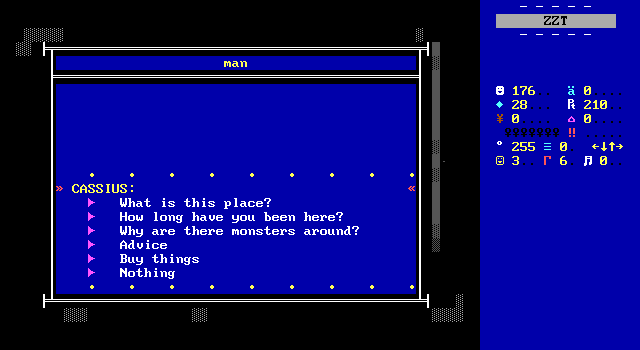

The man calls himself the watcher and the listener. He has been sitting in this room for two thousand years waiting patiently for the chosen, the one who will "liberate the slave countries of the east". ...Every time this game makes something up I'm immediately demanding to hear more.

Sadly, I won't get to, as the chosen isn't due for another 200 years. Credit to this game for having a dude like this and then immediately shutting down the player being that one.

Most of what he has to say about the caves, and what's going on amounts to very little. From a practical standpoint his purpose is twofold. Pay him for puzzle hints, or pay him to buy health and enemy drops rather than having to fight them yourself. The hints can be helpful if you overlook the candles needing to be touched from every side. The drops, really don't matter. If you're engaging in combat, you'll get them. If you aren't, there's no reason to bother trying to forge better weapons. A lot of this might change if there was a second chapter for these items to carry over into. With the game as is, a man who has been sitting in a room for literal centuries manages to be one of the least interesting things in the game. Question Mark's at least got that going for him.

Fade To Black

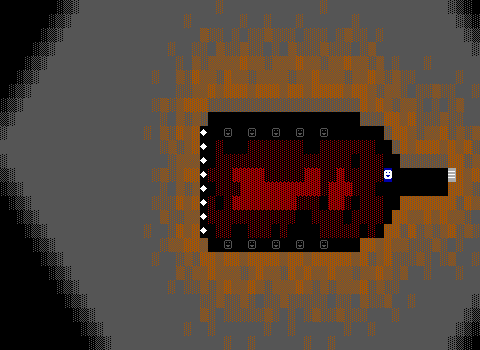

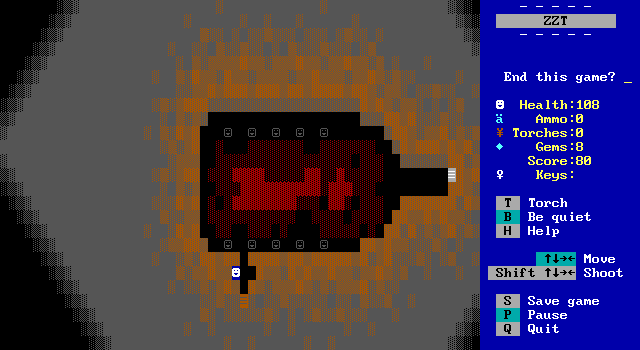

Successfully passing your candlestick quiz leads to an empty room. Like actually empty. A black void beckons to Cassius who enters the space only to have the door slam behind him. The room he finds himself in has no walls, light, or landmarks of any kind, leading to panic setting in along with the feeling of another presence in the area. Attempting to flee while lost in the void he trips and falls unconscious when he hits the floor.

The end. No moral.

Final Thoughts

Despite its issues, I did really enjoy this one. Question Mark proves himself very capable of wearing a number of different hats when it comes to game development. The story left me wanting to see it developed further. The early puzzles were impressive, and the endgame puzzles decent. The action is unique, and leaves quite the impression. Everything feels experimental, still in need of some work, but all the basic concepts explored in the game feel like they can definitely work. At the very least, the theory is sound. Set some initial expectations, throw a sudden curve-ball, and then dare players to find a way out of a cave filled with frightening monsters and strange puzzles. All of which has extra layers thanks to Cassius's strange dream as well as the carvings that hint at the real threat.

It's the execution that leaves room for improvement. The caves are mighty boring to look at. A dull example of ZZTers' obsession with grays and browns for "realism" rather than embracing how other colors can create much more memorable locations, even if they're not going for a cartoonish technicolor look. This is a game where magic is real. You can make a game that doesn't look nearly identical in monochrome.

Of course, it's not really the graphics that hold the game back from its potential. Some poor decisions have certainly been made that make the game very difficult to get players to want to engage with it as a cool game to play and not something that needs to be worked through outside of the game. The mandatory order for pulling levers is bad enough, but to reset everything if the wrong lever is touched? Nothing pulls players out of a world like having to open it in the editor to figure out what they're doing wrong.

This is than amplified with either the enemy placement or the cave's design. Enemies could really stand to take a more active role in going after players, or at least sprinkle them around a bit more generously. The enemies are so passive that it would be no trouble at all to avoid combat entirely, an incredibly bizarre decision given how the fights are some of the most impressive I've come across. It's not likely to be that easy a solution however, as the repetition makes each subsequent fight with these enemies less and less interesting. A smaller cave system would make it harder to avoid fights and greatly speed up the time spent crossing uninteresting looking boards with few if any interactive elements to be had.

Other mechanics like the weapon upgrade system are so obtuse that even as someone that would have loves to try them out, I never figured out how. Aspects like this and the carvings that bring the story to the next level are behind so many hoops for players to jump through that they're hardly there at all. The pacing also leaves a bit to be desired as you'll hardly get to use any new weapons even if you manage to acquire one somehow.

All of this makes the game feel incomplete, which it is, but ZZT games with sequels that never happened are quite common, and many still received plenty of praise regardless. The Guardian suffers for introducing things that it assumes you'll get to explore more thoroughly in a future that never arrived. As a standalone world, nothing that gets introduced has any chance to be explored or explained, and so you get an unsettling mystery where all you can do after playing is come up with answers on your own, never getting to see what Question Mark really had in store.

Regardless, there's still a lot here worth taking in for those familiar with the expectations of ZZT-spelunking games, especially of the era. Compared to typical dungeon crawlers, The Guardian is slower, more interested in its story, and excels at standing out in its presentation of a novel combat system and puzzle-centric design. For such a game released after Deceiving Guidance, it offers similar appeal without feeling derivative. It's just a shame that unlike Deceiving Guidance, there's no conclusion to be had here. I'm surprised this game seems completely overlooked. Nothing on the old z2 forums mentions it, nor was I able to find any reviews from the era. It's a game with obvious promise, and just as with Prisoner, something I'm certain I'd have been really into as a young teenager at the time.

Nowadays, the combat is worth experiencing, and if you don't mind a mystery that is intended to have more answers that you'll never get, the story is worthwhile as well, but expected to get tired of holding down an arrow key as you cross board after board of empty cavern unscathed. The Guardian is an overlooked gem with some notable flaws in the cut, but it's still quite a find. Question Mark should be proud of what he created here, a compelling dungeon crawling RPG that can still surprise players decades later.