How about something for dessert?

Today we're going to be exploring Cherry Pie, Tseng's sequel to November Eve. It's a pretty big departure from the previous game, created after Tseng's own pretty big departure: retiring from ZZT. Of course, "retirement" rarely lasts long when you're that young, so maybe it's no surprise that Tseng continued to create ZZT games after having called it quits.

This is a game I went with simply because I don't believe I ever played it, despite being a big fan of the first game for as long as it's been around. The original is a game where opinions have gotten more mixed as years have gone on thanks to its considerable cut-scenes and limited gameplay. Though that criticism isn't a new take. Even older reviews , including overall positive ones, make note that players are in for a lot of reading presented in slow flashing lines at the bottom of the screen. To address this, the sequel does away with most of made November Eve an original ZZT experience, taking things in a brand new direction. But was that change for the better? And can Tseng strike gold again?

Going by the silence in the review section, it may be an uphill battle.

Of course, before we get into all that, the first question that needs answering is why this game is called Cherry Pie in the first place. The answer, will neither surprise you nor leave you satisfied with the answer. Which is to say, it's a "Tseng-ism". The game's information screen explains, that Tseng liked to call ZZTer "Lord of Chaos" "The Lord Cherry Pie". Why? I have no idea. But according to Tseng, this means that game could just as well have been titled Chaos. And so, it was chosen to be part of the game's title.

To his credit, I went into this game thinking of it as November Eve 2, but the name has actually grown on me. It's the right level of weird without venturing into pure nonsense. The name flows a little better as well imo. Plus, given the very limited connections to the previous game seen in this sequel, it really stands more on its own.

As the official November Eve-liker, the appeal here is not at all the same as its predecessor, which was a weird fusion of Parasite Eve ZZT remake turned parody thanks to Tseng's substantial cast of characters from Da Hood used across pretty much all of his games replacing all of the original game's characters. Cherry Pie itself is a more original action game with no connection to Parasite Eve II, a game which wouldn't be released in the US for a few months after the release of this game.

Glancing at a longplay, about the only similarity I can see is that both games have their first level take place in a tower, which may have been gleaned from the Japanese release in December 1999 showing up in a magazine somewhere, or simply a coincidence.

Don't Call It A Comeback

Tseng cites his return to ZZT (they always come back) as being because of the "dire" condition the community is in. Due to a lack of decent games being released, Tseng has come out of retirement to show us all how it's don, and perhaps snag one last Game of the Month award for the road.

"ZZT is dying" has been a panicked decree for basically its entire existence. MegaZeux in the mid-90s offering a more technically superior medium, an insular community aggressive to newcomers in the 2000s, the struggles of running the program when Windows began to stop bothering with MS-DOS program support...

And yet 2000 seems like a rather strange year to specifically make this claim. Especially from such a prominent name. Tseng himself began his ZZTing retirement with a very smooth exit. The third Gem Hunter in January, a remastered special edition of the second game the following month, and on that same day a massive anthology with all the Gem Hunter games as well as a number of scrapped projects. Tseng himself had already done a lot of the heavy lifting to ensure that Y2K was going to be a good year for ZZT.

Still, if Tseng had an opinion on something, he had enough clout that folks were going to hear him out. Yet, looking at 2000s releases without his name attached, things still don't seem all that dire. That year brought both Bloodlines games, which baggage of its author aside, seemed really impressive. Scooter and Koopo The Lemming were some quality puzzle platformers inspired by Lemmings. Last Momentum offered a fast paced arcade racer with a twist. That's not even getting into the handful of titles that have aged poorly that were better received when they were new. All of these are pre-November Eve 2, with plenty more unique, bizarre, and creative games to follow as the year went on.

I mean, come on, you can't say no good games are being made hardly a month after A Dwarvish-Mead Dream! Banana Quest and LOME start off the summer of 2000! Just the Game of the Month list alone is enough to show ZZT is doing great in what wound up being its second most prolific year for releases. There's no shortage of bad games too of course, but that's always been the case.

This motivation comes off as strangely aggressive and unnecessary. It sets up Tseng to fail. If you're making claims like this, you best not miss when it comes to sharing your own creation. I'm already feeling primed to find any faults I can before getting out of the menu! Show us then, oh great one, what makes a good ZZT game.

The Premise

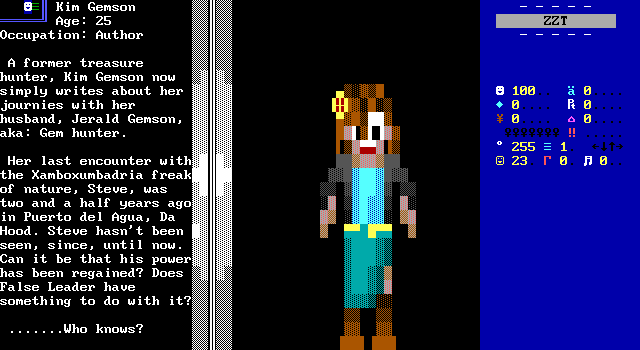

Two years after the events of Gem Hunter 3, Gem Hunter and Kim have wed, and started a family with their firstborn child, Joey. Kim is finding success as an author writing about her adventures with Gem Hunter. Gem Hunter meanwhile has retired from hunting and taken up ...professional sports? Now he's playing "Hood Ball" for a living. Life is good.

Everything was peaceful until one day Joey went missing. Gem Hunter was out of town for a match, leaving just Kim to find a note written in blood. It was "Mister Z", the mysterious villain introduced and made responsible for all the evildoing in the Gem Hunter series's third game. His identity was kept hidden unless players found every last gem in the game. Here though, while the alias is still used, Tseng assumes players are already familiar with Z's true identity of False Leader, outright spelling it out in the note twice.

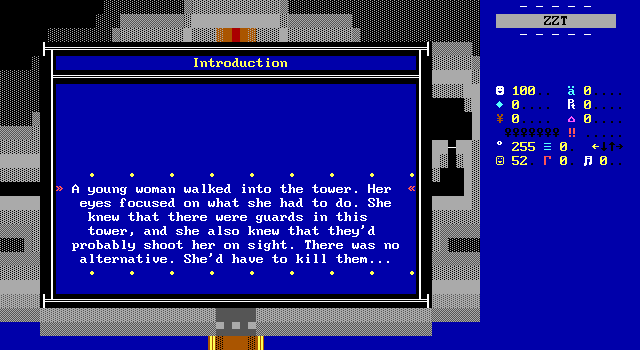

Gem Hunter's space baseball gets the usual hero of the series out of the picture, and gives Kim a reason to take up the protagonist role for the first time since November Eve. Something similar had to be done there as well, with Gem Hunter suffering and injury and Kim being from Earth rather than Da Hood offering her biological immunity to its villain Steve's ability to manipulate the Hoodian equivalent of mitochondria. Women in ZZT games made by teenage boys rarely get the greatest portrays, but Kim has been handled well. Gem Hunter may be the star of the game, but whenever Kim has been given the opportunity to kick some ass instead, she's proven quite capable. Both characters are the type that would love to take on Mr. Z if given the opportunity, no kidnapping required.

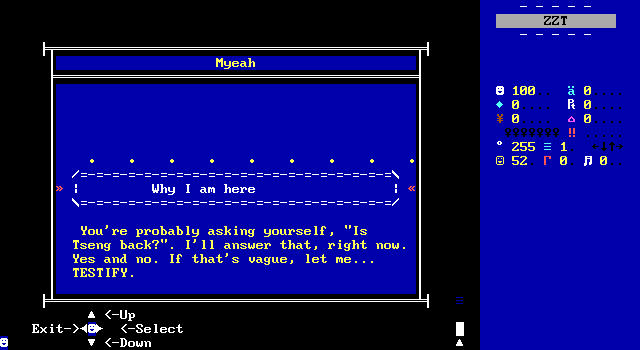

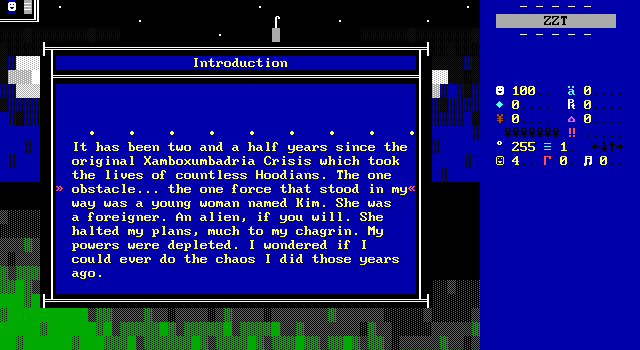

The introduction before players get to start sets a tone for the game that won't last long. A lot of Cherry Pie provides a surprising first impression. Things are far more serious here, really trying to build up Steve ans Mister Z as a threat in contrast to the more aloof storytelling of Tseng's other games where the protagonists are too powerful to worry about anything.

This won't last.

See?

For those who have played their share of earlier Da Hood games, the tonal shift is impossible to miss. Kim's mission is going to involve killing a lot of people, and she'd really rather not. But in this world, it's kill or be killed. Compare this again to November Eve where we get to watch Gem Hunter knock a doctor unconscious when they try to administer a needle. There's this brief moment where the weight of what she's going to have to do is actually felt, instead of being brushed off to get to the action.

The introductory credits here certainly might make you think this is a game to be taken seriously. Don't. This is still a Tseng game, and you'll be laughing soon enough.

Recipe for Cherry Pie

Kim's quest to find her child, discover and usurp Steve's latest plot, and maybe do what Gem Hunter couldn't and defeat Mr. Z/False Leader is a pretty tall order for a game so short. Unbeknownst to me, Cherry Pie is under-baked. The game was never actually finished, with Tseng tacking on an ending screen that boils down to "And they lived happily ever".

Outside of the introduction narrated by Steve, the character makes no appearance in what's actually here, making the game much more of a generic Da Hood action title starring Kim rather than a sequel to its well-received predecessor.

What you do get, is three complete levels, and if you do some editing, a brief glance at the unfinished fourth level. There are no RPG elements, no glut of characters, and most importantly no lengthy cutscenes. If you find yourself agreeing with the many who criticized how much of November Eve was spent reading flashing text as smiley faces stood around, Tseng has designed Cherry Pie for you.

If you were a fan, well, hopefully you're a fan of Tseng's games in general, as there's really nothing to recommend to anyone hoping Cherry Pie will offer a second slice of the original.

Despite the break in genre and tenuous connections to the past, Cherry Pie gives players a pretty decent action game that uses Nadir's Lebensraum as a rough guide for how ZZT action should be done, while maintaining its own feel.

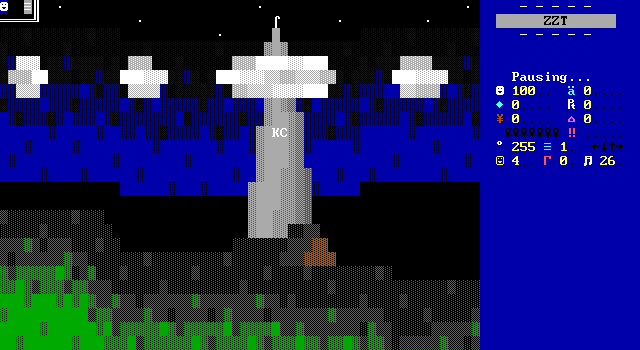

Each level opens with a kindly brief introduction screen or two to guide players in the transition from level to the next. Cut-scenes they ain't. They instead utilize still images and a nice escapable message window with all the text readable at your own pace. Unlike the first game, the story here doesn't really develop during these screens. Kim contemplates where she's going now, and why she wishes she hadn't in a few cases. They are a welcome inclusion though, helping establish exactly where Kim is at any given moment. For such a short adventure, Kim winds up traveling quite far, with the KC and the Sunshine Band Tower only encompassing the first two levels.

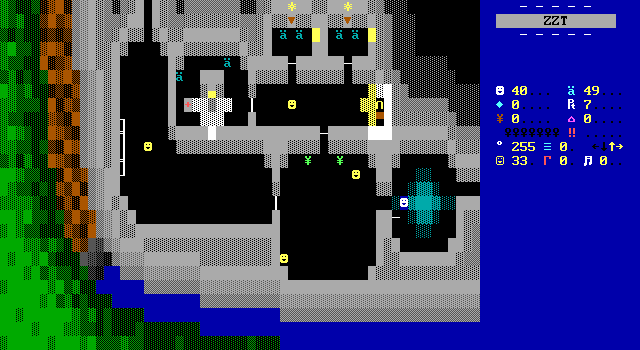

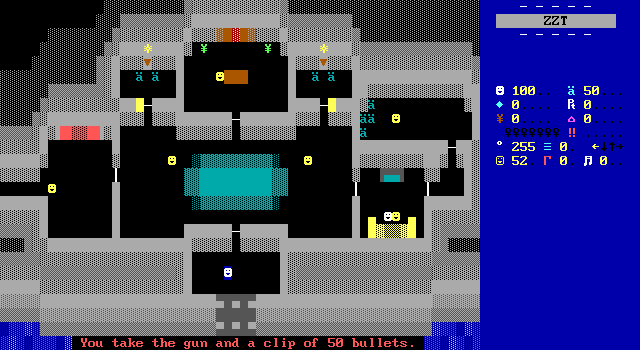

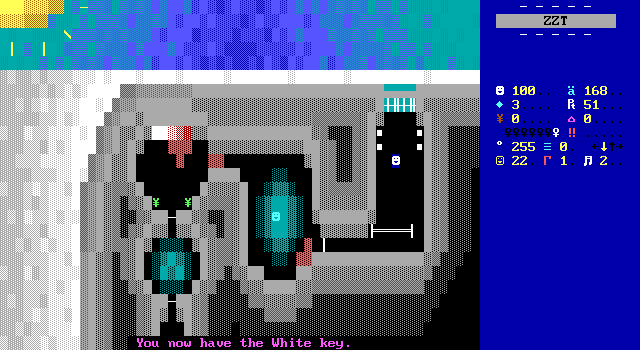

The gameplay boards meanwhile keep the open door, receive fight style of combat seen in Lebensraum, only without the fog of war. Lebensraum's biggest innovation was in keeping the contents of boards relatively hidden from players. You could see the outlines of rooms, but everything was invisible to the player until the door was opened, allowing Nadir to surprise players not only with sudden ambushes, but some unexpected decorations which would reveal themselves as well.

Tseng takes the simpler approach, opting to keep everything there in plain sight all along. This makes it much much easier for him to create rooms, and a lot easier for players to navigate boards. It's a decision with its pros and cons like any other. Having everything be visible at all times makes it far easier on players to know where they can fall back for health and where they should tread carefully if hurt.

Not having invisible walls reveal themselves as rooms are entered also gives Tseng the opportunity to give his boards proper backgrounds. Obviously, this wouldn't work with Nadir's game as it would mean clear outlines of secret rooms. In Cherry Pie, Tseng's game gets to look a little nicer this way. Instead of plopping everything down in a void of darkness, Tseng fills out his settings, and maintains some consistency between boards. The earliest boards of the tower have a moat surrounding them, with the background focusing more on the sky as you ascend. The spaceship uses the scrolling star field effect, and what little can be seen of the unfinished fourth level offers a glimpse at some very nice looking mountains at night with a snow effect to boot.

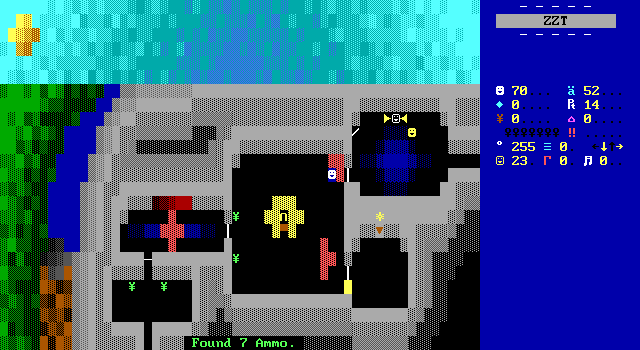

For the action genre where visuals are usually glossed over, Cherry Pie finds itself among the better looking ones, especially given its age. There's so much more color here than the muted tones seen in Refridgerator Raider (1998), Lebensraum (1999), Escape from Zyla Island: Special Edition (2001), and even Angelis Finale (2006)[1]. Tseng's visuals have always been good enough, but in this instance, "good enough" outclasses a lot of the competition where, for better or for worse, minimalism reigns supreme.

Ammo for Kim's weapon can be found in various supply closets where it's free to take, as well as by touching the bodies of certain enemies. Health arrives in packs which are rare, though quite potent, setting health to one hundred when used rather than giving a more modest amount. This lets players try to stretch them out, making it tempting to save them until Kim is on the verge of death rather than grabbing one when you're at around half-health and still have enemies visible on screen. It's a good system, one which prevents skilled players from gaining too much of an upper hand while also letting a struggling player have all their health worries go away as soon as they find one.

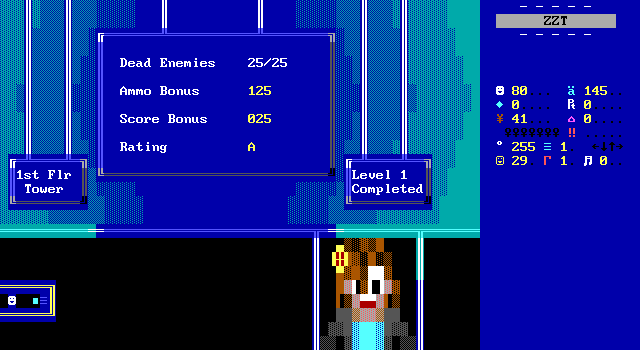

Each of Tseng's levels end with a status screen similar to what you'd see in Wolfenstein 3D or other early FPS games, and yet surprisingly absent from the Wolfenstein-inspired Lebensraum. Players are given a count of enemies killed and of any gems that were collected in the level which combines into an overall rating. These final ratings are then tracked via flags, presumably for some end of game bonus, as Tseng's games are so infamous for. In this game, whatever was planned for never got implemented, so the stats are just for personal triumph.

Interestingly, the letter grades are also accompanied by a special "You suck" rating below F, a grade so bad, that its accompanied by a game over. The requirements to hit such a rating are so low that I'm not even sure if it's actually possible to do so.

I wound up with A ratings on my first try through every stage just by making sure to kill everything I came across. It's easy to get if you go for it, as there aren't really any enemies you'd miss given the game's lack of secret rooms compared to Lebensraum.

The best part of this end-of-level scoring system is the ammo bonus counter. Kills on one level are rewarded with extra ammo for the next one. Your ammo count isn't reset ever, so the tighter ammo management of the first stage is quickly forgotten, which given how spongy enemies are is definitely for the best.

The worst part of this system is that the calculation takes forever. It's a fairly straightforward formula of one score equaling five ammo applied to convert all your points into torches for an overall final rating. Once this has been determined, rather than wipe the torch counter by a large number and then smaller numbers (ideally descending powers of two) as the #take commands fail, Tseng decrements it by one per cycle, creating an unnecessary pause of several seconds between everything being done tallying and the player being permitted to proceed to the next level.

Best Foot Forward With Two Left Feet

To make itself stand out from the numerous other ZZT action games available by this point, and to avoid being a "mere" Lebensraum clone, Tseng has a few tricks up his sleeve that make the experience unique and memorable.

Tseng's love of animated effects shines here, giving the game its own distinct presentation that keeps the game feeling fresh among its peers.

The first first thing players will notice before even entering the tower proper is the lighting effects. Animated torches on the walls of this exact style are everywhere in ZZT. What's far less common, is the way the light shines around the room, the flickering flames casting and removing light on certain tiles. It looks really cool in motion, and is a great way catch the player's eye immediately.

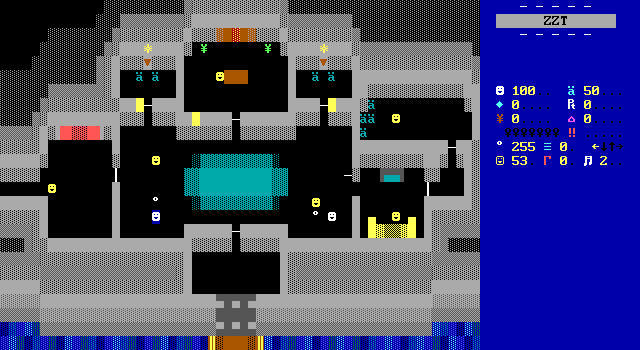

Once Kim enters the first room with guards, it's not long before the sounds of gunfire draw the attention of one of the stronger and more aggressive "special force" guards bursts in through the adjacent room and enters combat as well!

This is not something I've seen before. This sort of thing requires considerable effort versus just placing the guard in the room to begin with. It does wonders for making this tower feel alive, and for the player's actions to exist outside of the boundaries of the room they're currently fighting in.

There's a lot of potential here! Maybe later on a guard will sound an alarm and summon more from afar. Maybe you'll be able to block doors with something and keep them from getting in. If this is what Tseng is bringing to the table, I'm here for it.

Needless to say, at no other point in the game does anything like this happen. Ugh. Insert one of Tseng's own "Tseng is lazy" jokes here.

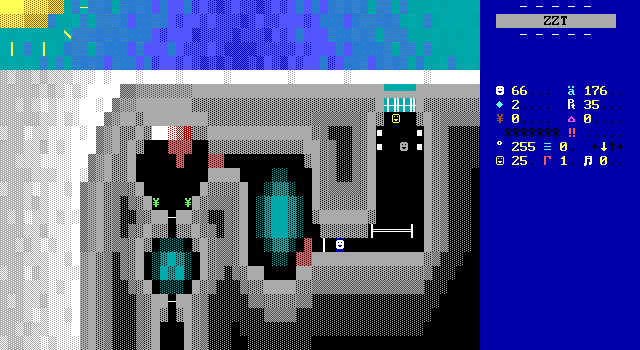

The second level pulls off another would-be-cool moment as Kim approaches a dead-end where two of the higher-up villains of the series are discussing the intruder. Crossing a threshold starts their conversation, but continuing into the room results in an immediate game over. Fair enough. You eavesdrop from behind a curtain or something and gather some information. Certainly not the first time a ZZT game has asked players to hide in some form.

The trouble is, there's a considerable delay between the conversation starting its code and the first line of dialog appearing on screen. With no message about taking cover as you spy, I just kept rounding the corner, and immediately being caught and killed for it. I had no idea I was supposed to sit and wait because it's unnatural to just stop and wait in a still environment!

All of that is the lead-up to the cool part.

As the conversation ends, a new enemy enters the board from below (well, they're hidden in a wall earlier of course), and begins making his way to Kim. Now this is a neat idea. Tseng changes the game by making a cleared board suddenly dangerous again, suggesting that any seemingly safe screen may have reinforcements arrive on a later trip. Combine this with them opening doors to approach the player and there's a sense of dread as you realize you're being hunted. This is a great idea that could really change the dynamic of how action games like this play out.

Needless to say, at no other point in the game does anything like this happen. Ugh. Insert one of Tseng's own "Tseng is lazy" jokes here.

Nah, really these effects are certainly a pain to incorporate effectively, and require the board layouts to permit such a thing in the first place. This only works here because it's a completely linear path so tracking the player is just a matter of moving where they would have had to to begin with. The marine enemy parks himself in the room just before where Kim was snooping if she tries to keep hiding. Opening the door to head backwards switches him into combat mode. The effect works great if players wait long enough to see what the object does. Heading out the door right away breaks the illusion, with the marine threatening to kill Kim as he begins shooting up a room that doesn't contain her.

I think this could be done better, but to do it at all is still impressive. Again, I just wish Tseng didn't throw away these good ideas after a single use.

- [1] Comparing the graphics to Angelis Finale is a bit of a stretch perhaps. It's first level has some cool abstract background machinery, and while later levels only do a little bit of dark gray water before fading to black, the game's tone and literal black/white/red exclusive palette make it feel like much more of a conscious choice than the other games which just don't have backgrounds.