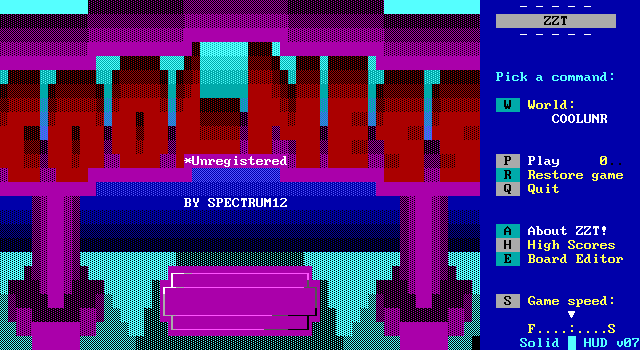

Coolness is unabashedly a game whose origin lies in the success of Code Red. From the moment players lay their eyes on the protagonist's home there can be no mistaking it. Williams is one of countless ZZTers of the era that played Code Red, placed it on their shoulders, and carried it triumphantly, considering it to be the most impressive title of its day.

That reputation lives on to this day, with the game still being considered one of ZZT's most important releases, not just for what the game pioneered, but for the ripple effect felt through games released afterwards. You can find glimpses of Code Red in everywhere you look. You can really feel the impact of the game though by the number of titles that it inspired that were never released. After Code Red the standards were suddenly higher, with many trying to take the wake up and save the world formula and surpass it, all too often succumbing to the burden they created for themselves. ZZTers found themselves promising multiple file adventures with dozens of endings, all trying to one-up Janson and become the ZZT community's next big thing.

Of all the attempts, Matt Williams is one of the few that managing to survive its own hype, and while it didn't dethrone Code Red, for its fans, Coolness was the next best thing.

Perhaps it was because the game received Janson's own blessing. Coolness wound up being released under the Software Visions label, the same company that published Code Red in what is the only instance I'm aware of of a ZZT company publishing a game by a non-member.

And usually, "publishing" and "company" amounts to little more than teenagers playing pretend. While the respect of being accepted into a prestigious company meant a boost to one's ego and standing in the community were real, usually that was all it amounted to, some kinds words and a few extra eyes on any future releases.

But Software Visions is one of the few ZZT companies that had honest to goodness revenue. Certainly not on the level of even the poorest professional, video game publisher, but enough that checks were cashed and disks were mailed. Being distributed by Software Visions meant the game was included on it's ZZT Collection, making Williams one of a very select few that we can confirm made money off of ZZT in the 90s without having directly worked with Sweeney himself.

Keeping Up With the Lipschitz's

Matt Williams does his best to escape Code Red's shadow. Everybody wanted Code Red but better, with Williams most of all not wanting to settle for Code Red but worse. At the same time, with the original adventure being unlike anything else in ZZT at the time, it was difficult to not just retread the same ground. When ZZTers ran with the concepts established in Town and the other original worlds, it came off as creating ZZT worlds as they were intended to be. Coolness is an early example of a ZZT game that wants to be another ZZT game, but Williams knew it had to be something more lest it be remembered not for its own merits, but as a Code Red rip-off.

This need to differentiate itself is especially apparent if you take a look at the game's demo, which features a glaring amount of content that maps up perfectly with Code Red. Exploding computers, the use of different colored line-walls to paint each room. The cupboard filled with food. Mention is made of an amusement park. It's a useful glimpse into the fate Coolness avoided of being the same adventure repackaged in a less interesting and less original manner.

Instead the game was wisely reworked. The game is still undoubtedly very much William's take on Janson's classic. Only now Williams is more interested in working with the concept of Code Red, an Earth in unknown danger, a teenager that stumbles onto the plot becoming humanity's unsung hero, multiple ways to arrive there; and developing them into something that still feels fresh.

Coolness is original enough to be more than Code Red 2, but whether or not that originally translates into quality, especially to surpass Code Red is another story.

Fletcher Long - Teenager, Philanthropist, Marksman

If you've played Code Red, Coolness will feel quite familiar. A teenager with free time and gun is let loose into the world with no explicit goal other than to enjoy their day. The Code Red-compatible drop in protagonist for Kyle Lipschitz is now Fletcher Long. The two are both mostly blank slates, defined by their actions rather than words.

And as both games espouse some big "Fuck around and find out" energy, exactly what kind of personality players will give them can vary wildly. Fletcher can become a local hero, saving his community from a bomber, a fugitive on the run from aliens that loathe humans with no qualms bashing, shooting, or electrifying anyone that tries to capture him, or just a nice kid that gives money to the homeless and takes money from bank vaults.

The appeal to the game is in seeing the unexpected ways in which things escalate, turning your weekday afternoon into the adventure of a lifetime. Teenagers dreaming of something exciting happening, of getting to be the main character for a change, are the basis of the wake up and save the world genre. Fletcher, as with Kyle, is an empty vessel for players to act out their own stories with. The intent being to let players go anywhere, do anything, and most importantly have their actions matter.

Having finally played through the entirety of Code Red last year on stream, one of the biggest criticisms I had was that while the player had an immense amount of things they could do in their home: unplugging Super Nintendo consoles, frying fish, vacuuming the living room, sleeping in, blowing up a computer, and so on, exactly how or why these actions mattered felt arbitrary, which made finding all possible outcomes rather difficult through play alone.

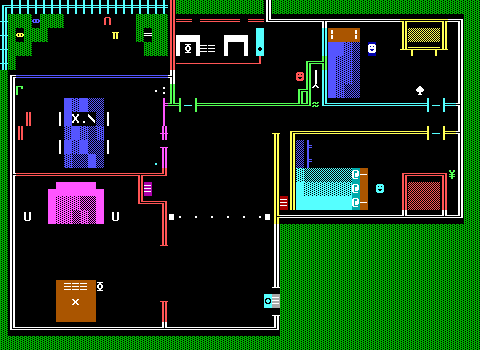

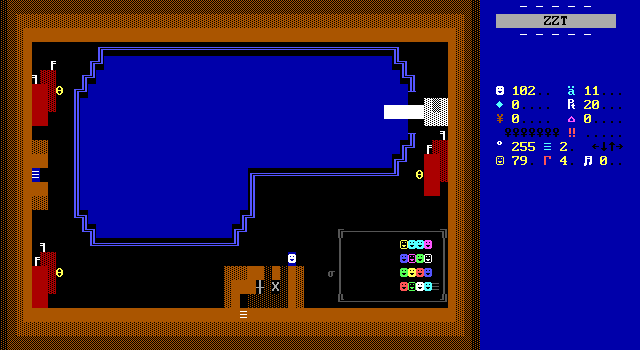

Williams streamlines the experience in Coolness. The early game options are spread out over a wider area, and feel more substantial. A mysterious laboratory conveniently located behind the Long residence features two strange machines protected by a barrier. Players are only allowed to lower one barrier, giving them a choice to make, and making it abundantly clear what they still need to investigate on their next playthrough.

The game is also more streamlined thanks to how eerily empty it can often be. Even accounting for every ending, Fletcher rarely gets to speak or interact with anyone. I can't think of any other ZZT game where you have coworkers, and can't speak with a single one of them.

His family is cast aside as well, despite his father unknowingly playing a major role in two endings. The game speaks of his father Marshall, mentioning how he went home for the day, but at no point does he make an appearance. Fletcher's mother Martha is mentioned only as an option when asked to identify yourself to a security system. Fletcher has no friends here, with only a rather bizarre message about his neighbor's son being a former friend before he got interested in death, machinery, and other "twisted" things as Williams calls them.

Mr. Marshall Long as well as neighbor Brian Hepshell exist just to give justification to the hidden bits of fantastic technology waiting to be discovered. Fletcher is blissfully unaware of the massive secret lab just over the back yard fence until his dog manages to create a gap in the barrier. The innocuous looking treehouse in his neighbor's yard contains an experimental weather machine. The strange machinery featured throughout the game were created by Marshall and Hepshell in secret, with the duo working mundane jobs as bankers and mechanics as a front, only to secretly develop civilization-changing technology in their spare time. This is a game of weather machines, teleporters, and matter-transforming devices. All of which can become Fletcher's toys to play with as he sees fit, and be destroyed by if he doesn't read the fucking manual.

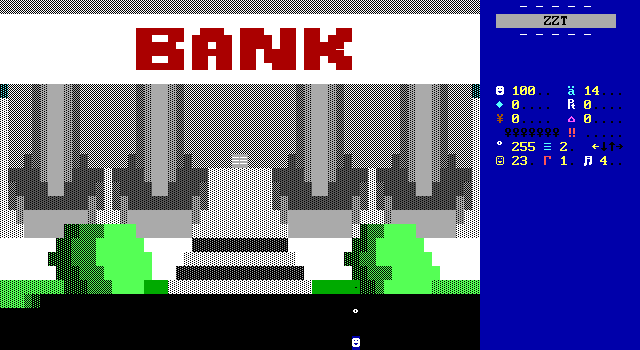

The unexplored background characters here give a real sense of mystery to the game. Fletcher is the main character today, yet this is hardly a case of an average kid with an average family having the adventure of a lifetime. This town is just plain weird. It's established quickly enough that anything can happen and the game benefits immensely. Players can see a passage behind a locked door at the public swimming pool, and they can't be confident at all that a pool will be the only thing there. Hidden switches can disable security lasers in the bank, but the vault still won't open. Something is always just out of reach to tempt players into finding out what they're missing to be able to see the other side.

Unlike Code Red where the many possible routes through the game close off within minutes of starting, Williams really teases the player by making sure they run into the first steps of each path, leaving them to wonder what would happen if they had a gem to give the homeless person that leaves the scene afterwards? What if they lowered the second barrier instead of the first? What is the point of the torch sitting on the front step of their neighbor's house?

Williams succeeds in keeping players thinking about not just what they're doing, but what they could be doing next time, which is perhaps Coolness's greatest success of all.

Post-STK Fidelity

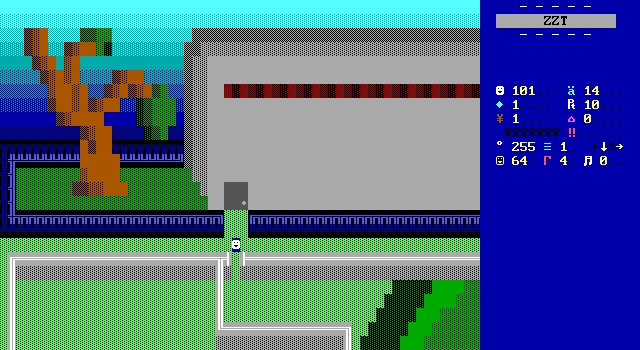

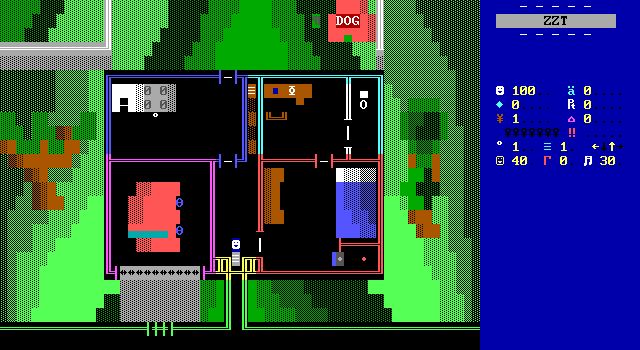

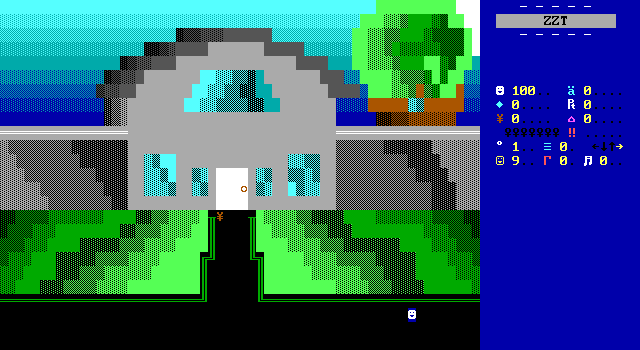

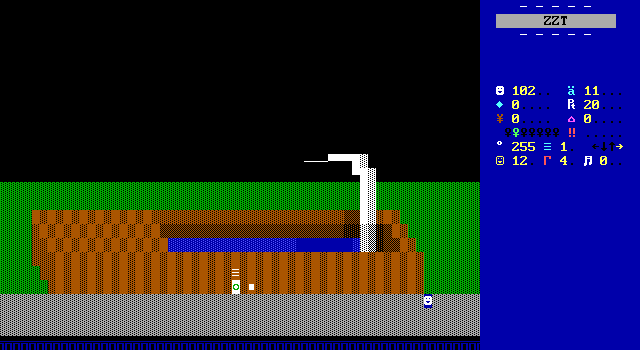

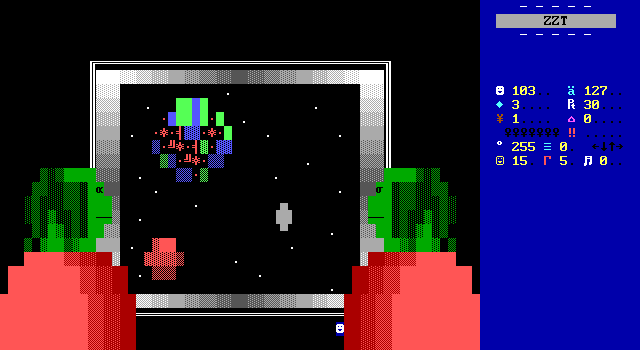

Coolness has one big advantage over Code Red thanks to coming out a few years later. Unlike Janson who was likely hex-editing every instance of special graphics in Code Red, Williams had trivial access to Super Tool Kit from the start. The game makes heavy use of dark colors and blending, something impossible just a few years prior.

Being designed with the full sixteen color palette in mind from the start results in a game with a striking look compared to its most obvious competition. Williams does a fantastic job creating his visuals for the game, with a number of gameplay boards that take advantage of the large space available and limited space in which the player needs to move. The game's nicer looking boards are genuinely some of the best seen in ZZT by this point in time.

It shows how much can change in three years. While the Long residence would fit in right next to the Lipschitz home, there are considerably more fine details. In Coolness furnishings like chairs and desks are much more appropriately sized to the player, and able to use STK brown for their wooden assembly. Janson was still working with stock colors, bolting large dressers to walls with line walls like everything else.

Janson's computer is a strange looking contraption, made up of more than a dozen objects to suggest a screen, printer, disk drive, and keyboard. It's a stretch to look at it and interpret it as a home computer setup in the early 90s.

Williams is able to use a more modern style, generally depicting a computer in a way one might still do today. It does still have an oversized floppy drive attached to the side, but the monitor with its built-in speakers is much easier to read as a computer.

Ironically, any direct comparison that favors Coolness over Code Red aesthetically is ultimately Janson's own doing. Without STK, Williams would've been in the same position as Janson for trying to create readable household items. Her collection of uniquely colored elements meant that going forward, anyone could use them without having to know about ZZT's internals.

Where Williams does something that Janson didn't, but arguably could have, is in the game's heavy use of shading.

This too takes advantage of STK, though using only the stock color palette of ZZT's editor would still be enough to capture most of the look. While Code Red has its home adrift in a sea of ZZT forest, Williams brings his world to life with colorful bands of grass, and trees constructed from browns and greens. It's more like an STK-enhanced take on Chris Jong's own art style.

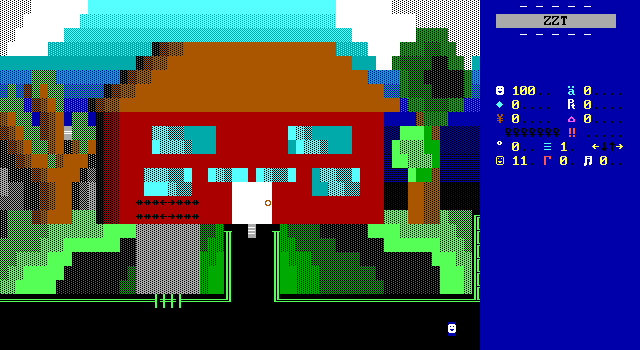

Williams clearly enjoys building up his scenery. The exterior of Fletcher's house, as well as his neighbors are some excellent depictions of ZZT homes, each with their own distinct shape, and consistency between other boards that take place nearby. The Long home has three trees adjacent that are still seen, with their shape and positioning maintained when inside.

The neighbor's home is never entered, but the fence behind surrounding it and the large tree with a treehouse window visible from the street again match up rather nicely with the backyard that players are able to get into.

Often times with these ZZT boards that take up the entire screen yet feature so little to actually do, I find myself getting a bit annoyed. I'd rather be moving quickly to the next interaction point rather than having to run across an entire board to move one house over. Williams makes his buildings so nice to look at, that it's worth the walk. The scenic route deserves to be taken here, in contrast to something like The Worse Adventure where buildings are just rectangular shapes of line walls with doors attached.

Alas, if only the entire game could keep up with its beautiful beginning. First impressions are everything after all, so if any boards were going to get this kind of treatment, Williams was right to blow people away the moment players leave the bank where the adventure begins.

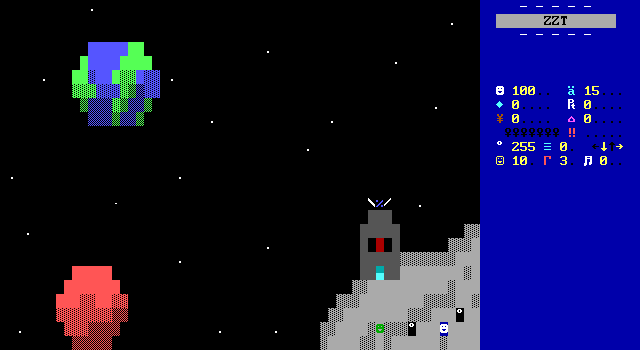

However as the game progresses, backgrounds return to black voids, grassy fields are made of nothing but default forest colors, and extra-terrestrial terrain is depicted with a flood-fill of fake wall. Sometimes the quality returns momentarily, such as a lovely sunset at an award ceremony before a large crowd in one of the game's endings. The moon also fares a bit better in its details than the outside world of the planet Folga3. Williams could have done a little more here to maintain consistent graphical quality throughout the entire world, though the challenge of finishing the game at all makes these cut-corners easy enough to explain the dip in overall quality.

Three Endings

In terms of marketability, Coolness can't compete with its number of endings, offering a paltry three in contrast to the unthinkable eight of Code Red. In terms of playability though, the scaling back of the project makes it significantly more approachable, especially for those wanting to see see the entire game. Coolness feels like a game where completing it 100% is within your grasp.

"[Coolness] won't have as many endings as Code Red did. But heck, endings doesn't make a good game. So far there are about three real endings. At the moment, COOLNESS is about 208k.

COOLNESS, at first thought to be three worlds is now cut down to one world. Also, once I posted a message at the ZZT Central message board that said: "I'm planning on making a COOLNESS for MZX!" (or something like that.) Well, if anyone saw that post, then forget it! I got the first couple of boards done, then I got sick of it and stopped. Spectrum12 would make COOLNESS a lot bigger, but he says: "I'm getting sick of working on it!" That's why you've never seen any games come out before that are done by me or Spectrum12. We always get sick of it, then quit. But don't worry, he says that he's going to finish COOLNESS (one way or the other) and upload it!" — Comthought

Originally, this wasn't going to be the case. One issue of the ZZT/MZX newsletter The N.L. includes an article written by Matt William's brother discussing how the game has been scaled back in order to ensure it would actually be finished. Exactly how many planned endings were cut is unknown. One can only assume the game was meant to match or surpass its predecessor in order to achieve victory by numbers alone.

These days, the idea of making a ZZT game with fewer than eight endings seems like a no-brainer, even for an open-ended game. Back in the mid 90s though, more endings obviously meant a better game, causing countless authors to start games and never finish them. Code Red unintentionally left a trail of vaporware in it wake.

Lucky for us Williams decided to apply triage and give us a digestible adventure instead of a cursed demo with no followup.

The game itself likely avoided the fate thanks to Williams realizing that the project wasn't getting done anytime soon and opting to scale things back. Given how well MegaZeux was stealing the thunder of text-mode gaming around this time, there was a genuine possibility that ZZT was going to fade away into obscurity, fully superseded by its far more hi-tech next generation counterpart. Williams saw the writing on the wall, and smartly shaved off the excess in order to create a complete package whose numbers might not have matched Code Red, but whose quality was more comparable because of it.

Unlike Code Red, which suffers quite a bit today due to how similar its endings are, Williams's three endings for Coolness are vastly different from one another. Instead of getting beamed up onto one of a million alien ships orbiting the Earth ready to destroy it, Fletcher gets to save the earth, or save the public pool, or just have one hell of a day exploring an alien world.

Where Code Red does do a better job is in making its endings accessible. It can certainly be difficult to get on all eight possible paths through the game, but players won't have much difficulty finding new paths until they've seen half or so. Gameplay alone can get players on most tracks. With fewer endings to find for Coolness, the moment you start to struggle, you're probably out of luck when it comes to finding what you're missing. If you're avoiding the editor or other means of getting information from the game, you'll certainly see more of Code Red than Coolness.

Folga3

Coolness has what might be considered its default path, where players are most likely to end up on, only to hit a roadblock where it seems they're stuck on a few boards unless they discover a hidden switch in some plants outside a computer store. It's easy to get locked onto this path and then get stuck, since the game doesn't really encourage touching objects multiple times, something that becomes mandatory here. Seemingly normal plants offer no reason to think to touch them again other than blindly touching everything repeatedly in hopes of finding a way forward.

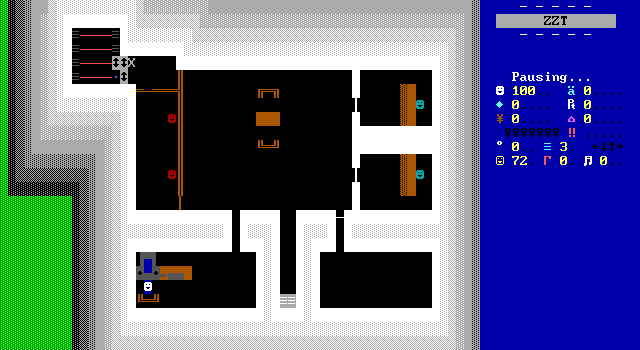

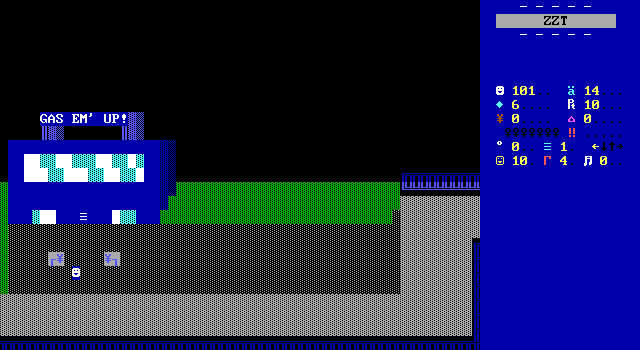

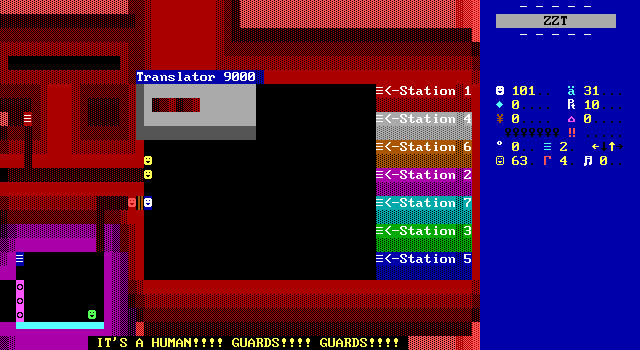

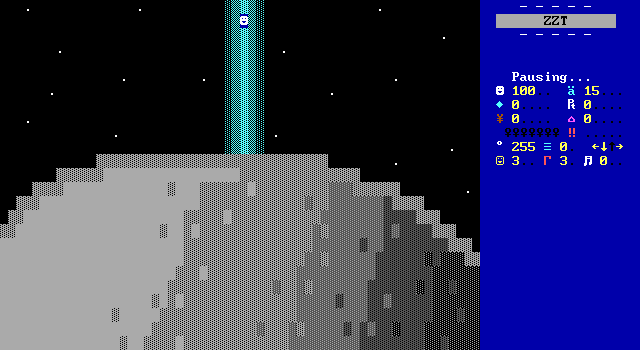

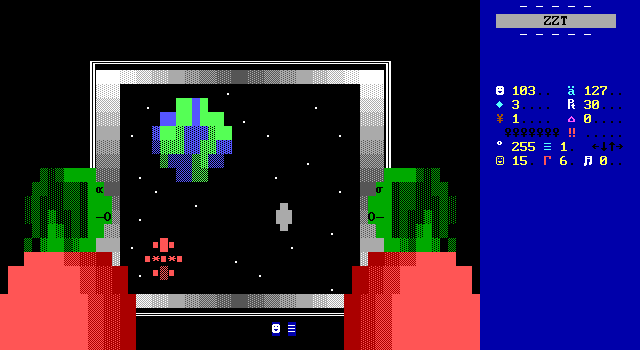

These plants hide a switch which reveals a spaceship concealed by a tree. Said rocket, once properly fueled and serviced, can launch players to the distant planet of Folga3. Humans are not welcome on the planet due to their violent tendencies, leading to Fletcher being locked up immediately once the alien inhabitants realize there's a human among them.

The escape leads to the death of several aliens, a self-fulfilling prophecy as Fletcher's violence is in self-defense. As with Code Red the space sequence is pretty brief. Players are locked up, break out, flee the receiving station, steal a spaceship, and pilot it back to Earth, making it home in time for dinner.

It's a rather interesting scenario because there isn't really a conflict here other than Fletcher getting locked up. The aliens want nothing to do with humans, but they're not blowing up the planet or enslaving humanity or anything you'd find in Code Red. The ending still parallels its inspiration though with both games featuring a moment of "Nobody believes your story, but think about it, how many kids have a spaceship?".

To me, this path is the best of the three, so it's fortunate that it is so accessible once players discover the hidden rocket. The puzzles featured here are the game's best, the intergalactic world-building is novel, and some of the game's fanciest visual effects, namely the rocket's reveal and the second ship's takeoff are really eye-catching.

The Mad Bomber

The second ending is by far the most difficult to reach. It requires doing a number of things that can only be done once making it very easy to break away from the path. If you're lucky, this means being funneled to the Folga3 ending, but there's a very real possibility that you'll just have to vaporize yourself in lasers and start over as well.

Players need to disable the bank's security lasers before reaching the rear entrance. They'll have to find a way to get a gem before meeting the homeless person behind the lab as he'll walk away if you don't have one to spare. They'll need to operate a device to turn a second gem into a key after everything else. This device can only be used once and can take a number of items as input with only one of them turning into a key and no way to tell what you'll get from the machine other than by using it. Then players will still need to activate a hidden weather machine before heading to the pool, otherwise it will be closed due to cold weather and the passage erased.

Everything needs to align to get to the pool. It gets kind of ridiculous honestly. Even as I went through the path for a second time since my original stream I still kept second guessing myself that I was doing things correctly, and that was with the knowledge of what to do floating around in my head already. Practically speaking, you're not going to find this path unless you start digging through the game in the editor to try and unravel what you're missing. Even then, untangling the order of operations can be quite confusing since one-way paths are numerous making it quite easy to realize you forgot to shut off the lasers or used your first gem to get the key and now have to restart.

Upon somehow managing to reach the pool, any hopes of summer fun are quickly dashed as "The Mad Bomber" has struck! Everyone has been locked up in a cage and dynamite has been rigged around the pool ready to blow at any minute. Fletcher needs to find a way to free the people and disarm the bombs, neither of which he's particularly prepared to do.

After one last puzzle, the people are saved, though the bomber remains at large. Regardless, Fletcher is a hero, having saved dozens of townsfolk and receiving the key to the city from the mayor. It's cute, and incredible efforts aside, goes to show you that this kind of game doesn't need the world's survival to be at stake in order for your actions to have weight.

Moonshot

But if you must get your Code Red fix and save the entire world from alien attackers, the final path through the game serves to scratch that itch.

The last ending is also the game's briefest. It could very well have been just as likely the "default" ending players get were it not for the fact that it's possible to close the path off entirely, and that even if the road is taken, bugs (covered in the next section) prevent it from being winnable without cheats.

The other endings are reasonably integrated into the world around them. Yeah, sure it's not exactly "realistic" for your neighbor's treehouse to have a weather machine in it or for a tree to secretly conceal a rocket, but there's an attempt finding a place for these fantastic locations in boring ole' suburbia.

To get to the moon, players don't need a rocket, they need to take a transporter found in the lab and just go there instantly, which is quite a surprise as the documentation for the device mentions that no receiving end had been constructed yet, so its use may result in you going anywhere.

Luckily for Fletcher, instead of dying on a harsh airless world, he is gently dropped on the surface of the moon, paying no attention to the unexpected breathable atmosphere. Players expecting to immediately suffocate will feel a mixture of relief and "haha why can I breathe on the moon". (Don't worry, the alien's log explains that they set up a temporary atmosphere while they worked.)

The moon is large in terms of board count, shaped to cover a 3x2 area of boards to better depict its round shape, but many of the boards exist only to define that shape. There's actually very little to do there.

One board has a single hostile alien, with the only others seen on this path following Code Red's lead, repeating the strange decision to have most aliens just be asleep. One part of the game that I didn't catch in either recent playthrough is the ability to stab this alien with a sharpened flag pole for an instant kill. You don't need to do this, and the flag itself isn't actually attached to what Fletcher is holding, but it still gives me a powerful mental image of a teen impaling and alien on the moon with an American flag.

Other than that though, the moon is pretty boring. There's a cave filled with silver and gold that Fletcher can't take, a deadly machine waiting to be activated and destroy the Earth, and a parked alien ship which contains transporters that can be used to return safely to Earth.

Technically, there are four endings here. Fletcher's job is to save the planet by re-calibrating the death beam to target the alien's home world of Mars, then safely head back to Earth. Of course, Fletcher doesn't have to re-calibrate anything. It just means that his return to Earth is short lived.

The path through the game might not be the best, but the brief cinema of the aliens watching their plans result in the destruction of their own planet is a fantastic moment for ZZT cinema. This is one instance where Williams does surpass Code Red including cinematic art boards like this showing the alien's talking and emoting as their plans either succeed or go awry.

It's a shame that under normal circumstances, you'll never actually get to see this ending.